From the queer underground scene of Europe’s capitals, Ali + The Stolen Boy emerges with a potent voice, singing for the existence and resistance of the community. With their new single Uranus, Ali + The Stolen Boy is bringing about a personal and collective revolution. Hailing from Paris and Milan, the non-binary artist combines their history of performing with an experimental lyrical complexity. Written in Italian and French, Uranus traces the echoes of Alix’s past, and of their resilience.

Blurring the lines of electro-pop and rock, Uranus is infused with the history of art rock, with the signature use of harp, guitar and synth throughout the track. As the first single from the upcoming EP, Uranus gives a clear taster of the music to come, with a fusion of analogical instruments and experimental electro arrangements. From growing up in a Southern Italian family, to discovering their collective family and the queer scenes of Europe’s capitals, Alix’s work is anchored in their personal history, and is fused with an intersectional approach to music making. When we speak, Alix has just been nominated winner of Mission Diversity during Linecheck Festival, part of Music Innovation Hub, an initiative that supports six international projects working on representation and intersectionality. Fresh off the back of the announcement, Schön! speaks to the artist about their multicultural background, voyages, self-discovery and the importance of collectivity.

Your parents are from Puglia, but your family was scattered all over Europe. Where would you say your passion for music came from?

My grandmother was my first immersion in music. She used to sing a lullaby to try to get me to sleep, which she sang in a dialect from Puglia. While she was singing, so as to talk to other people without waking me up, she would transform what she was saying into music. She just invented it all. We were extremely close. There was something ritualistic about it; it could go on for hours. I think that’s where my passion for Jazz comes from, from that same pattern of improvisation.

Rhythm plays a huge role in your writing. How do you work with that?

I’ve always loved rhythmical patterns – I think it comes from the language and the culture that I grew up in, that of Puglia, where the traditional music, songs like Pizzica are based on a rhythmical pattern. This is very common throughout the Mediterranean.

It connects me to my grandmother. She would cradle me in her arms, to the rhythm of her song. Music is linked to touch and to contact. That’s where my work on the body comes from; it’s why I started experimenting with dance, movement, bodies.

You moved to Paris when you were young – how did the city transform you?

My mother speaks French, she lived there when she was a teenager, as part of my family is French. Paris was somehow familiar, but it was also a discovery – it is so intrinsically linked to the arts, to the references that I had studied over the years: theatre, literature, dance, art. Paris has always been a crossroad, singers, artists have always converged there for centuries; Jazz singers from all-over the world congregated in Paris. Arriving there when I was so young from a background where I had never had access to any of this, and stepping in the footsteps of all these great songstresses, I really wanted to lead the bohemian life; I drank and sang. I didn’t have any money, so it was a struggle too. Now that Paris has shaped me, it’s home – the North-East of the city is a cradle where all my relationships, friendships and memories live. It’s where I write.

Paris is also where you discovered an underground queer sphere. What impact has this had on you?

Since I first moved to Paris, I’ve continuously met artists, activists and performers. I built my own consciousness, with my friends, as to how my presence in the world is linked to structures, to class, to privilege. I learnt how my presence on the planet has an impact. I discovered the punk scene of Paris. My friends opened me to Paris’ trans-feminist and POC writers, from Virginie Despentes, to Glissant, to Monique Wittig. All these people converge in the streets of Paris during protests – that’s where my political upbringing took place.

Your work in the performing arts also took you all over Europe – from Lisbon, to London, to Paris – what role have your performance projects played in your life?

I trained as an actor, a dancer and in movement analysis; my career in theatre gave me the discipline that I use in music. My approach to dramaturgy also comes from this, the structures of songs comes from the fact of knowing that I have to tell a story. A song is a chapter – like in theatre, there are scenes – so I still construct my work in the same way.

I think of my music as having to be seen too, not just heard. Music has to be danced, to be lived, to be interpreted. I have the stage in mind from the very beginning. It’s the only way I can translate my emotions and stories into music.

Your questions on gender also burgeoned in Paris – what transformations did you go through?

Paris is the place where I discovered that I could give names to what I felt physically. I started using ‘queer’ and ‘non-binary’ in relation to my identity, which was super important and of course intrinsically linked to the language I was thinking, working, living in.

And what about Milan?

I’ve just arrived, I’ve met a lot of amazing artists and musicians, with whom I’m working. We’ll see how this Milan-Paris split will work for me and for my music.

What’s the story behind Uranus, your new single?

I was in a very esoteric space when I wrote it; I was exploring gender in relation to seer saying, to visions. I had already written 3 different songs; I read Apartment on Uranus by Paul B. Preciado, and it was the final shove that I needed to give shape to the material that I had. Uranus has become a sort of introduction of myself to the world, a coming to terms and declaring my existence.

One of the main things that people ask me is “Where do you come from?” – as my personal story is fragmented in many places, I’ve always felt like I come from another planet. I prefer to see my journey as a voyage between different spaces, but also between layers, between different social spaces, between different temporal frames.

You’ve previously said that the personal is political. What does this mean for you?

Everything that is linked to a person, a body is political. I cannot see the difference between something personal and something that is political. How I behave with friends, whether I establish toxic or misogynistic relationships is a political choice. These are the micro-revolutions that we all operate. It can come through music, choices, and relationships.

I try to work behind-the-scenes on this, with the consciousness that a lot of people don’t have easy access, because they’re womxn, queer, POC, disabled or belong to a minority. Music is always political for me, and I think artists are starting to become aware of the responsibility we have in the narratives we share. I would like to contribute to changing the structure of the music industry, but I am conscious I cannot do it by myself. The personal is political, but it is also collective – you cannot change anything by yourself.

The role that gender and violence play in your work is evident. What is your story with gender violence, sexual violence?

Gender and sexual violence were the reasons I stopped writing music and singing for many years. What happened to me happened in the culture industry. The perpetrator was in a position of power, and I was a minor.

The vulnerable part of my voice comes from that trauma, but I also perceive my music as a roar, a cry – it’s a place of anger and beauty. There’s always a ‘fuck off’ hidden in my voice. It’s also an invitation to anyone who experienced this to use their voice to say fuck off, fuck you to the people who deserve it. Music can be really, really powerful. Now voices are rising in all the fields of various industries, and I’m so glad to speak out with all of them.

What role does music play in terms of collective or personal emancipation?

I did a concert 10 days ago in Milan, and one of the most powerful moments was when I singing a song about mansplaining. I wrote the song when I was in London, drunk in Dalston, 5am – a guy tried to tell me how I should be living my life. When I sang the song, I asked all the people there to think of someone who had done this, and we sang the chorus together as a collective fuck you to this person. There is a powerful political poetry to music.

I believe in music as a means to tell something. Not only something to listen to alone and ‘feel something’ in total isolation. I love listening to music while walking through crowds of people, I like to feel connected to what is happening around me. I want music to be shared. It’s about saying something to someone else. People perceive it, I think, when they’re at my live shows.

What’s behind The Stolen Boy?

I have always had people project this boy identity on me, but I’ve never identified as a boy. If I say – “that boy doesn’t exist” – I feel like I’m stealing that boy from their imagination, one they invented, but hasn’t really ever existed. It’s a sort of hologram, where I let people project what they want. There’s something very ironic about it.

What comes next for you?

We’re in full recording mode – we’re finishing the EP and in the studio. I’m also recording a single entirely in French. And of course there are the shows, in the coming months.

Ali + The Stolen Boy’s single “Uranus” is out now.

words. Nino Sichinava

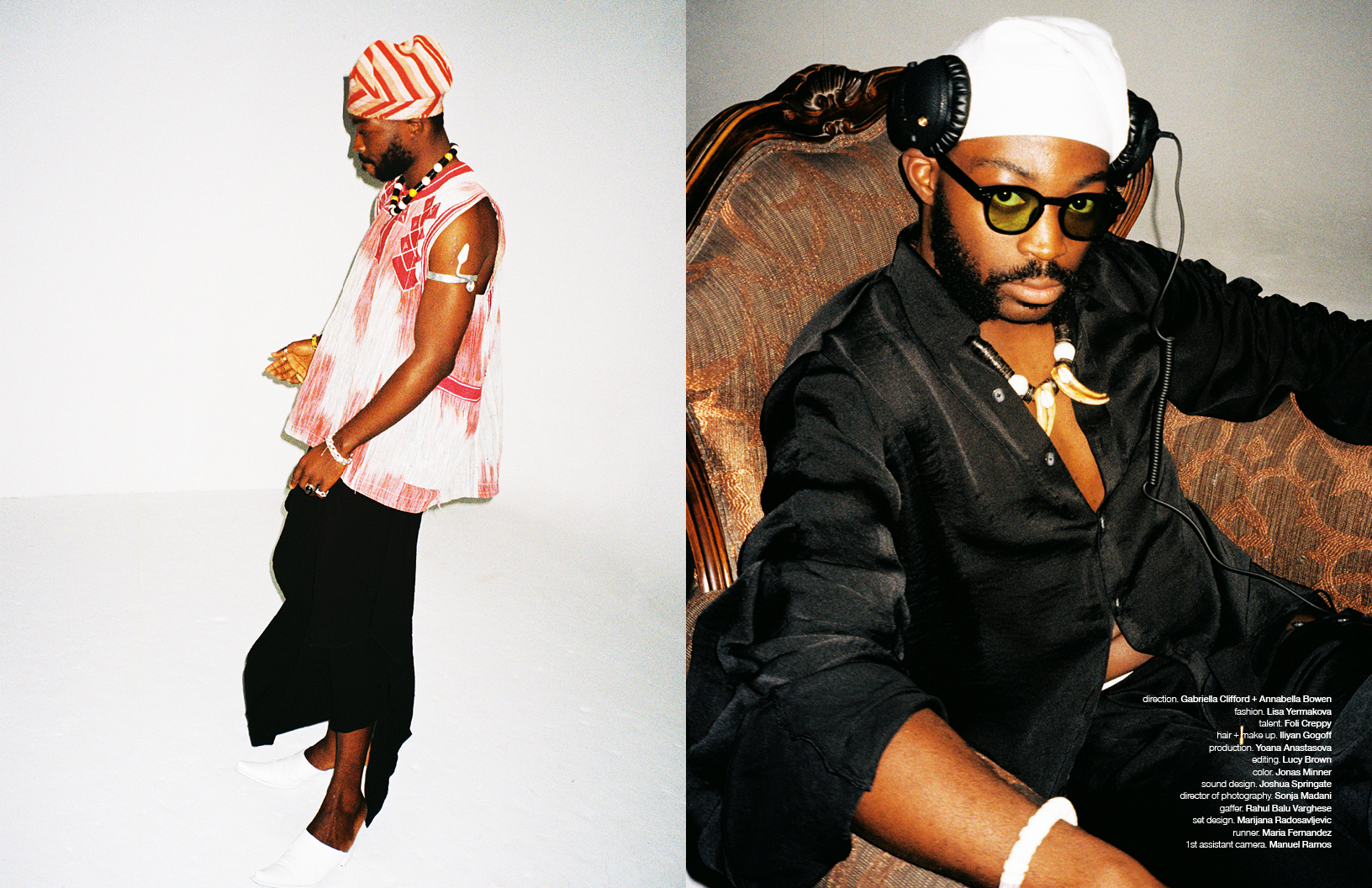

Uranus – fashion credits

Vitelli, Kaleem A. Iverson, Dadamax, Anna Dionisi, Nita, Tuono Design, Youwei, Lost in Echo, Alberto Zambelli, PWC and Gentile Milano.

directed & written by Alix

a Divergence Studio production

director of photography. Théo Clark

fashion & creative. Divergence Studio

editor. Federica D’Addato

makeup. Alessandro Pepe

hair. Davide Nucara

set design. Edoardo Giustetto

cast. Ian Alieno @ Ewa Talents Management, TaintedCore, Mira Pantera, Carlitox Manzano, Sophie Margot, Kappa and Chiary No.

bondage artists. Kappa & Rita La Zia

fashion assistant. Elda Miniero

uk production. Reblis Films

backstage photographer. Libera Mariotti

locations. Phoebe Zeitgeist Teatro & Giovanni Isgrò Studio

Special Thanks to Giovanni Isgrò, Giuseppe Isgrò, Alberto, Jermay Michael Gabriel and Lisa Turnbull.

Schön! Magazine is now available in print at Amazon,

as ebook download + on any mobile device