Rashid Johnson, “Antoine’s Organ”, 2016. Installation view Garden of Earthly Delights, Gropius Bau, Berlin, 2019.

© Photo: Mathias Völzke, courtesy: the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

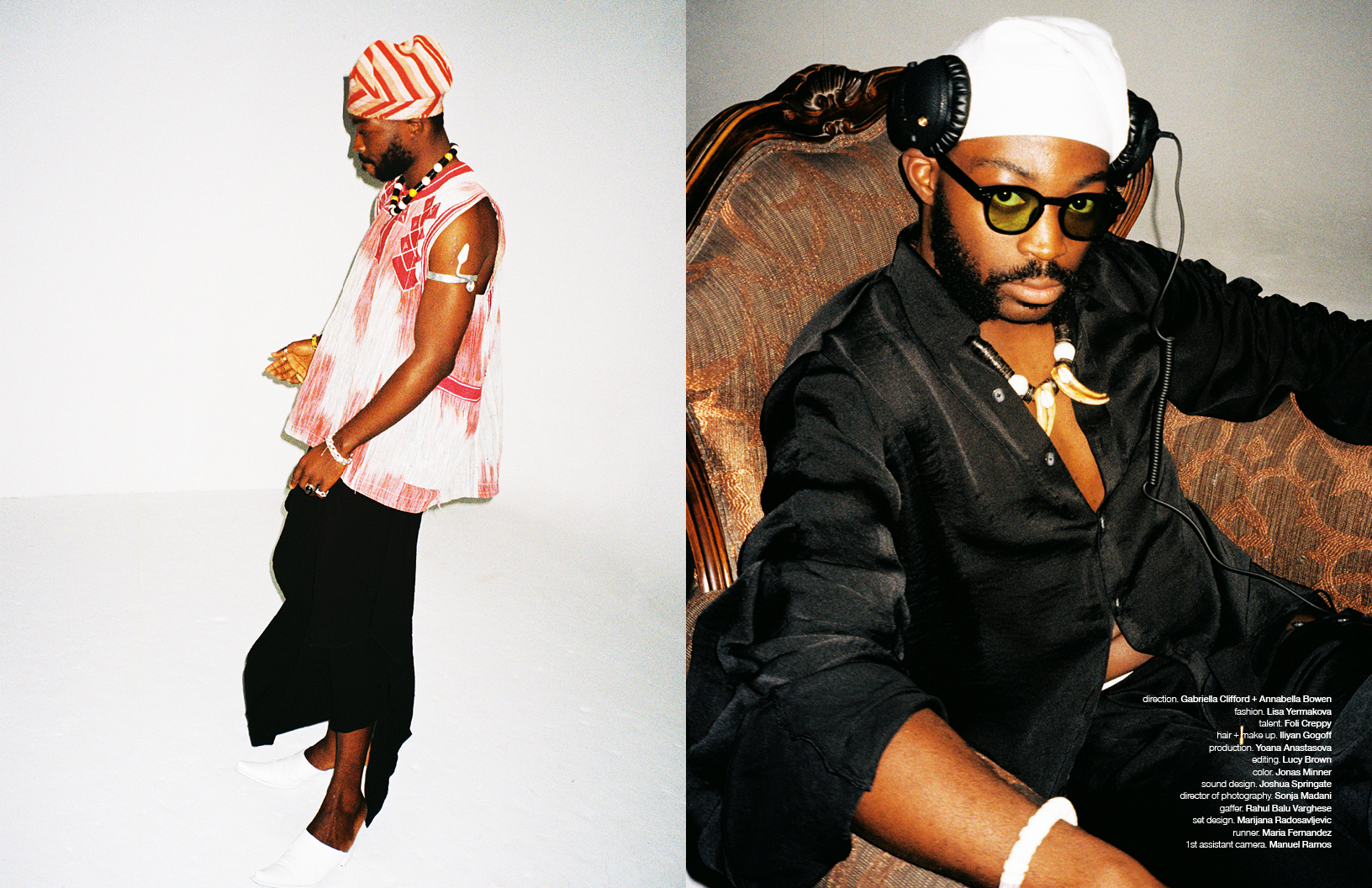

Stepping into the main atrium of Berlin’s Gropius Bau, Rashid Johnson’s “Antoine’s Organ” towers in the lofty neo-Renaissance atrium of the 19th-century museum; emanating a soft, glowing light. The piece, part of the ongoing “Garden of Earthly Delights” exhibition, features a rigid black steel grid from which large, leafy potted plants sprout amongst stacks of books, folded carpets, and the occasional decorative object.

Walking closer, even more details come into view: books — by the likes of W.E.B. Du Bois, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Debra Dickerson, Richard Wright, and others — are stacked neatly; and the voices of anti-racist activists emerge from a television, laying out the next steps for black liberation. Johnson’s work captures the liminality of the garden — not entirely natural, not entirely artificial. It also signals that here, gardens are immersive — not flawless oases nor spots for neo-colonialist vacations. They’re contested political sites.

At the Gropius Bau, the “garden” is approached from five angles, visitors are told via maps handed out at the entrance: from the catch-all of “Paradise/Utopia/Dystopia” to the rather trendy “Anthropocene” through “Urban Gardening,” “Garden as a Structure of Thought,” and “Colonialism/Migration/Botany.” But it’s these same dichotomies presented in the first work that come up again and again throughout the exhibition — tensions between escapism and our political reality; between those forces of nature and those of anthropogenic destruction.

Hicham Berrada, “Mesk-ellil”, 2015.

©Hicham Berrada, Photo: archives kamel mennour, courtesy the artist; kamel mennour, Paris / London & & VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019.

The first few rooms of the exhibition take on a more anthropocentric approach, examining how we relate to or hold power over garden spaces. Hicham Berrada’s dark, fragrant installation “Mesk-ellil” blocks out all-natural light so that the daily cycle of the night-blooming jasmine flower (dormant all day, emitting what she calls an “erotic musk” at night) is flipped to allow visitors a chance to experience the scent even in broad daylight. With a simple black-out curtain, the artist upends the life of these plants, tricking them, and forcing us humans to be aware of our power — of the violent force of our mere presence.

Korakrit Arunanondchai, “2002–2555.” Installation view Garden of Earthly Delights, Gropius Bau, Berlin, 2019.

© Photo: Mathias Völzke, courtesy: the artist; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York & & C L E A R I N G, New York / Brussels

The more critical side of this coin comes from Korakrit Arunanondchai’s video installation “2002–2555″ — an ode to his grandparents’ garden after the 2011 floodings in Bangkok. This installation confronts us with a different source of violence: climate change. Large canvases on each of the walls show flames and thick yellow brushstrokes, juxtaposed with the soft sweetness of his grandparents in their garden.

Heather Phillipson, “Mesocosmic Indoor Overture”, 2019. Installation view Garden of Earthly Delights, Gropius Bau, Berlin, 2019.

© Photo: Mathias Völzke, courtesy: the artist

Another diatribe against climate change comes from Heather Phillipson’s installation “Mesocosmic Indoor Overture.” This multi-screen video installation depicts a post-climate catastrophe life, where humans become compost. Crossing the mulch-covered room, visitors see screens mounted on tree stumps. Phillips imagines an apocalyptic scenario where plants have overtaken humans — which, on the worst of days, doesn’t sound half as bad.

Yayoi Kusama, “With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever”, 2013. Installation view Garden of Earthly Delights, Gropius Bau, Berlin, 2019.

© Photo: Mathias Völzke, courtesy: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / Singapore / Shanghai YAYOI KUSAMA.

There are a few moments throughout the exhibition that can feel escapist. Yayoi Kusama’s now-iconic dot room, “With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever” — ostensibly referring to the dys/utopia of a garden — is perhaps the perfect example. Over a white background, Kusama’s trademark coloured polka dots take centre stage in the fun installation, which houses larger than life flower sculptures.

Homo sapiens sapiens, 2005.

Audio-video installation (video still).

© Pipilotti Rist, Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine

Pipilotti Rist’s “Homo sapiens sapiens” features a video of nude woman, her body fragmented and reassembled kaleidoscopically against a backdrop of neon ferns and psychedelic sunsets. The woman rotates slowly, seemingly mid-air, upended in gravity. Then the video jumps between close-ups so extreme that her body parts are no longer identifiable. It’s easy to get lost in the Swiss artist’s dreamscapes, but the harsh reality of “Colonialism/Migration/Botany” awaits.

Australian artist Libby Harward’s “Ngali Ngariba” scrutinises the garden as a political force. Plants native to Australia and imported to Europe are presented under glass vivariums and paired with recordings of endangered indigenous Australian languages. Harward notes the concept of controlling nature was the Western coloniser’s, not native to the plants’ region and returns our attention to the artifice of garden spaces. They are arranged, or curated even, to be microcosms of our limited understanding of the world. Her work also functions as meta-criticism extending to the broader museum system in which she operates.

Pipilotti Rist, “Homo sapiens sapiens”, 2005

Installation view Garden of Earthly Delights, Gropius Bau, Berlin, 2019

© Photo: Mathias Völzke, courtesy: the artist; Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine

opposite

Heather Phillipson, “Mesocosmic Indoor Overture”, 2019.Still from multi-screen video installation.

@ Heather Phillipson.

Transcending these tensions and dichotomies is Hieronymus Bosch himself — whose oeuvre served as the starting point for the exhibition itself. A reproduction of the centre panel of “The Garden of Earthly Delights” (the original triptych currently housed in Madrid’s Museo del Prado) is on show at the exhibition. The work on display is attributed to an artist “after Hieronymus Bosch” from 1535-1550, approximately twenty years after Bosch’s death. The centre panel depicts nude figures in various states of sinful behaviour, but the risk of paradisiac expulsion pervades, according to the curators’ reading. There’s no doubt why Bosch’s work has been lauded for centuries, but perhaps its greatest strength in this context lies in its ability to bridge the divide the more contemporary works fall prey to. “The Garden of Earthly Delights” captures the whims and joys of such a space but engages with the dangers in equal measure.

After Hieronymus Bosch, “Garden of Earthly Delights (centre panel)”, 1535–1550.

Oil on wood, transferred to canvas, 182 x 168 cm, private collection.

“The Garden of Earthly Delights” is practically the only non-contemporary artwork — the other is a Persian garden carpet from the late 18th century. Transhistorical exhibitions have been having a moment recently, as Nina Siegal reported in the New York Times. From 2018’s “The Shape of Time” at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna — which paired Kerry James Marshall with a Tintoretto— to the ongoing commitment by the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem and the M-Museum in Leuven, museums strive to dismantle chronological displays.

But this approach risks running into one particular problem: contemporary art is frequently flashy, extravagant, and excessive in comparison to its older counterparts. As a result, the older works’ subtlety can get lost in the bright lights and sheen of contemporaneity. Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights” avoids this. The painting — though more delicate than, say, Kusama’s dot room — is filled with whimsical and thrilling details of sin and excess, engaging even the most overstimulated viewers. The humour that is often read into Bosch’s work – the notorious man with a flower up his rear is the classic example – works in his favour. With this seamless blend of old and new, the whole exhibition reminds us to look for prescience in unexpected places.

Berliner Festspiele’s “Garden of Earthly Delights” is on at Gropius Bau in Berlin until December 1.

words. Alexandra Leake Germer

Schön! Magazine is now available in print at Amazon,

as ebook download + on any mobile device