coat. Ziqi Liao

vest, trousers + tie. Sona Singh

shirt. Savil Row

shoes. Marni

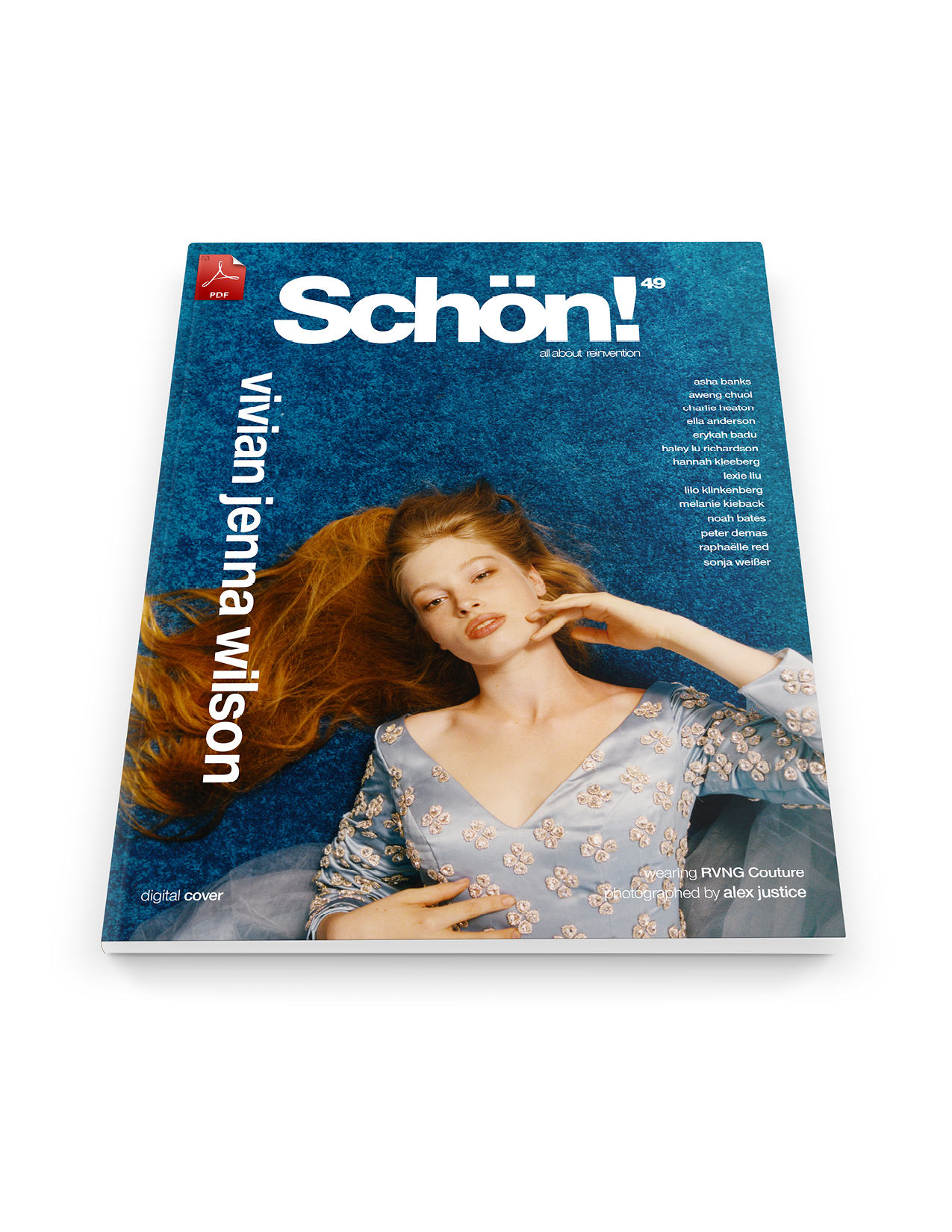

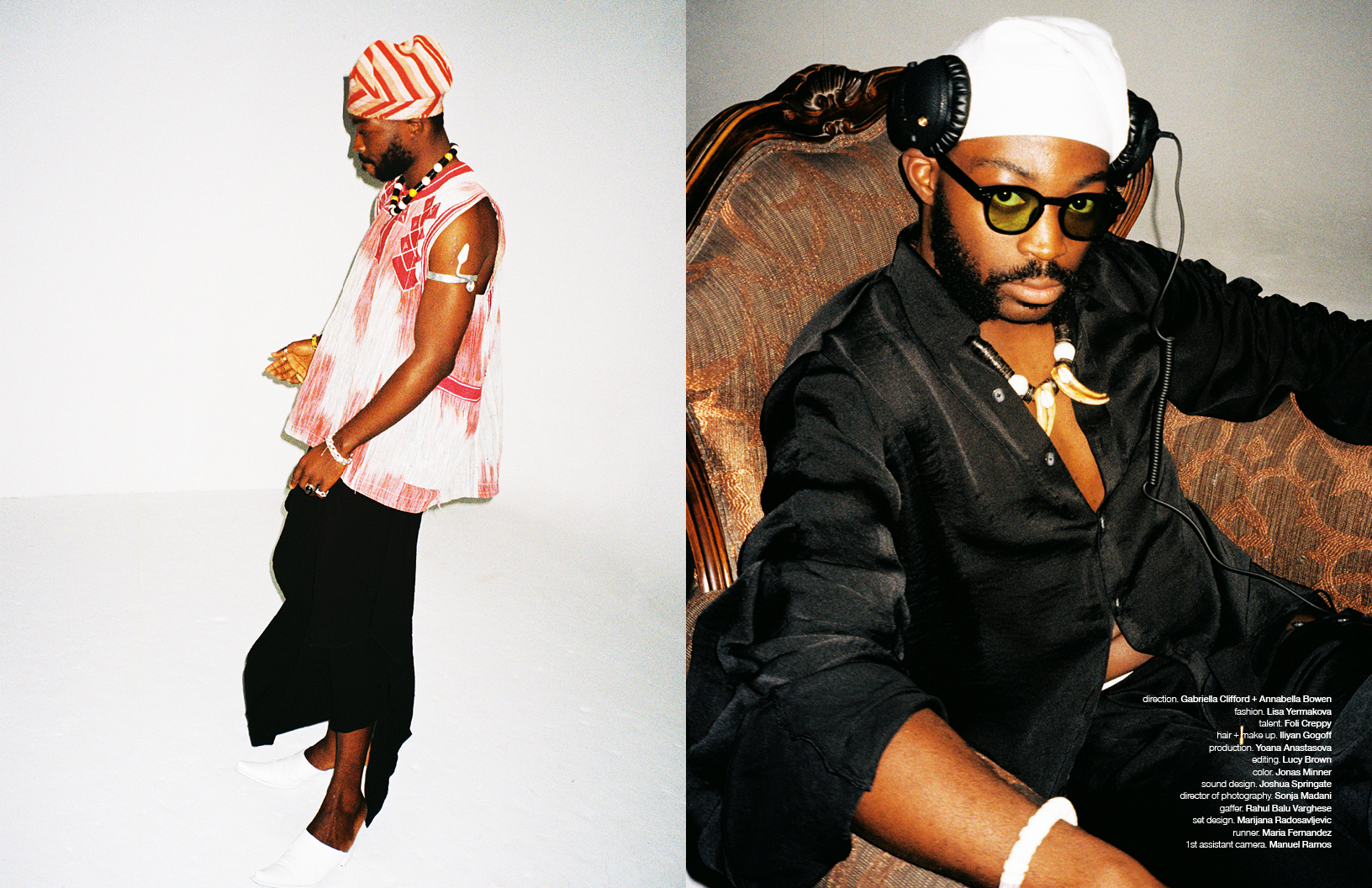

Tanzanian-born and London-raised, Tiggs Da Author has been making waves in the music scene for over a decade, blending genres and creating tracks that resonate across the spectrum. With collaborations featuring musical icons such as J Hus, Skrapz, and Jordy, along with multiple-time collaborators Nines and Sam Wise, he has lent his soundscape to practically the whole gamut of UK favourites. Today, he meets Schön! with such ease and warmth that invites deeper conversation.

Upon the interview with Adam, or Tiggs Da Author – as he’s been called for most of his life – the hyphenate picks up our Zoom call from the studio while giving a soft chuckle; the studio has become a second home. Though he’d never consider actually working from home. One might call it work-life balance, but Tiggs adds how much he enjoys the commute and not getting distracted. Unexpected, though his velvety voice, paired with the jazzy tunes, should have been an early sign of such ease.

He chats with Schön! a bit about football, a sport he played semi-professionally for some time, along with his enduring love for Manchester United. Centred and intuitive in his speech, Tiggs reflects on being known as the kid who could kick it on the pitch, yet none of his school friends would have guessed he’d pursue music, let alone become a rapper. It was a time when Grime music was on the rise, and the underground scene hadn’t quite gained mainstream popularity yet. Unlike the other boys freestyling during lunch breaks, Tiggs describes himself as rather timid. Instead, it was poetry that eventually brought him to the studio. Here he is, sitting in front of vinyl records lining the wall, talking about the importance of knowing your niche, boys’ mental health and what’s to come.

faux fur coat. Raphaël Xie

opposite

faux fur coat. Raphaël Xie

jeans. Diesel

shoes. Marni

Could you talk us through the story behind Tiggs Da Author? How did Adam become Tiggs?

As a kid, it wasn’t cool to have a normal name. Everyone had their something. It’s like, one of those things that make you look extra cool, almost like a superhero. At the time, I wasn’t as creative with it, I used to wear the Tigger bags, the Winnie the Pooh and Disney characters, and all that. I had that Beanie hat, and I was like, yeah, I’m just going to call myself Tigger. Eventually, when I started making music, it made sense for me to call myself Tiggs Da Author because everyone was already stuck with Tiggs.

Do you feel a difference between Tiggs Da Author and Adam as personas, or is the name simply an extension of who you are?

There’s definitely a difference. On stage, I become a completely different person -you’d never guess I’m actually quite shy or introverted. When it’s time for music, it’s like stepping into another character. The same goes for the studio. Writing is a deeply personal process for me, but when it’s time to perform, I shift into that persona, where I can fully embody the energy of the music and perform.

What’s Tiggs listening to right now? Are there any songs or artists you’re especially drawn to right now?

Honestly, a bit of everything. I’m really into Little Simz and Cleo Sol too. Her music just really calms me down. Michael Kiwanuka and Maverick Sabre are on my radar as well, I’ve been listening to some of Maverick’s new work. Anything with strong lyrics pulls me in, so I’m drawn to well-written folk rock, soul, and Afrobeat too, like your Burna Boy and Omah Lay. Good lyrics just hit differently, you know?

coat. Ziqi Liao

vest + tie. Sona Singh

shirt. Savil Row

opposite

coat. Ziqi Liao

vest, trousers + tie. Sona Singh

shirt. Savil Row

shoes. Marni

jacket. Homme Plissé Issey Miyake

shirt. Ziqi Liao

tie. Sona Singh

opposite

jacket + trousers. Homme Plissé Issey Miyake

shirt + shoes. Ziqi Liao

tie. Sona Singh

You’re into a wide range of genres, that come through in your music. With roots in Tanzania and your upbringing in South London, how does that dual identity shape your sound, and what role does heritage play in your music?

Man, it plays a huge, huge part. I feel like my Tanzanian Heritage played a part a little bit later in my life, whereas when I started music, I was more influenced by my immediate surroundings. Grime was blowing up, and artists like Wiley and Dizzee Rascal really struck a chord with me because I could relate to their struggles. It was only when I became a student of music I really started to research more, and I’d just find myself watching, I don’t know, Jimmy Hendrix or James Brown performing live for hours. That’s also when I discovered Fela Kuti and downloaded a ton of his stuff.

And at the time, I started going back and forth from London to Tanzania. I heard local musicians playing Afro-jazz and Afro-soul, and it clicked for me. I thought, ‘This is what I need to do.’ When I returned to London, I immediately wanted to put a band together. I started reaching out to musicians on Facebook, and that’s how I found my guitarist, who’s still with me today. That was the start of my journey and a shift in my sound toward soul music.

Music feels like it’s always been woven into your life – both parents being so musically inclined, with your dad on bass in a band and your mum deep into Motown. Ever thought about sampling one of your dad’s old tracks?

Back then, they had jazz bands, but they never recorded anything. Music was consumed much differently than we know it. It’s wild because the only way to hear their music was to actually see them live. They used to just literally go around Tanzania and East Africa playing shows. And there were a lot of jazz bands around, each was just named after its area. Let’s say if you were in London, it’d be like Dalston Jazz Band, Shoreditch Jazz Band, Stoke-Newton Jazz Band. That’s what they used to be called. Yeah, it’s crazy. And for some of them, you can find some YouTube recordings, even though the quality is obviously terrible, but you get that idea.

jacket. AGRO Studio

string vest. Sona Singh

leather trousers. Auralee

It’s been three years since your debut album Blame It On The Yutes dropped; a title that seems to hint at the pressures and expectations placed on youth. What inspired you to choose that title, and what themes does it encapsulate for you?

It’s my first album, so I wanted to capture my mind state of when I was a teenager, adjusting from growing up in Tanzania to starting life again in the UK and where my mind was at. One of the main things I felt was that, even if we were just hanging out outside the shop, it felt like a lot of teenagers experienced this, where you feel like the world is against you. The older generation in the area thinks you’re the cause of everything, just causing trouble. You feel like the government isn’t doing anything to help, whether it’s building more youth clubs or finding ways for us to put our minds and time to good use. Even in the music scene, we might be the young ones trying innovative things, but the older generation blames us for messing up the whole genre.

At the same time, this project touches on social commentary and has some conscious themes. Some songs even have political undertones. That’s how I’ve always been; aware of everything and always asking questions. Even at 13, I’d find myself watching the news before school. My friends would always be baffled, asking why I did that. I just wanted to know everything. Because knowing meant understanding why things were happening and maybe even how I could make a difference. I didn’t want to waste an album just chatting shit. I’m always going to include social commentary in my work.

Reflecting on your journey, what do you see as the most significant challenges and opportunities facing artists today, and how do you think the landscape has evolved since you first started your career?

Man, I feel like the biggest challenge for anyone is longevity because everything changes so quickly, and you’re only going to stay relevant if you can adapt. Unless you just make timeless music, that’s one way to do it. I remember when I started music, it was a completely different sound. Even in grime, everyone was going through a phase of making dance records to try and get on the radio, and they had to dress a certain way. Then it changed. Grime got a rebirth, and there was a new energy, but that also changed. You can see it goes in cycles, so you just need to find a way to avoid chasing trends because they’ll never stop changing. If you’re in that game, you’ll be in and out in a year, two years tops. We’ve seen so many artists go through that.

When I started, there was no TikTok. Now we have these tools to market our music, but you don’t want that to be the only thing defining you, like, ‘Hey, I’m a TikTok star, that’s it.’ Everything I make has to go viral, and then I’ll release it. If that’s your only way of marketing yourself, you’re stuck. So, the best way to go about it is to find your own lane.

opposite

black fur collar. Stylist’s Own

pony skin jacket. Sona Singh

denim shirt. BOY London

trousers. Pleasures Curfew

boots. Diesel

opposite

pony skin jacket. Sona Singh

denim shirt. BOY London

trousers. Pleasures Curfew

boots. Diesel

You started out writing poetry, does that still play a role when you’re creating new tracks?

I feel like now I do it mainly on voice notes. I’ll have lyric ideas, and I’ll just record voice notes so I can remember them. I definitely don’t write on paper anymore. That is long. I get it. It’d be nice, but I’m not running around buying pens all the time. That is a myth. So that’s mainly what I’ll do I’ll record on my phone, but I’ve got a pretty good memory. I like to think of the concept first, like what my intentions, are and what I’m trying to say, especially because I love lyrics. I’ll sit there for a couple of hours just thinking about the whole concept and what perspective I want to speak from. And then I’ll just start thinking of lyrics, and then it will rhyme at some point. But yeah, so I feel like that works for me.

Creating music can be therapeutic, almost like journaling, but there’s often this stigma that men are more reluctant to discuss feelings openly. Do you think this hesitation comes from societal expectations around masculinity?

A hundred percent. Guys hold back a lot more because of this idea that’s been placed on us since we were young. We’re told boys don’t cry. You can take that however you want, but it means that whatever problem or mental struggles we’re going through, we’re not really supposed to show emotions because society sees that as a sign of weakness.

Humans are humans. Everyone has their own issues and goes through different struggles. Guys should feel free to express themselves. And I feel like in music, you’ll find musicians who really express themselves in a song in a way that might even surprise you. He might have friends around him who didn’t even know what he was going through until they hear the song and think, ‘Fuck, no, is this real? This is how you really felt about this?’ And that’s because, for some of us, it’s the best way to release how we feel. Sometimes, you feel like even if you explained it to your friends, they wouldn’t understand.

You’re a do-it-all all; a rapper, singer, lyricist, producer, and potentially a bunch of other things that I missed out on right now. Do you feel that people have tried to categorize your work, put labels on you, or place you in a genre box?

Yeah, I feel like it makes it easier for everyone to put something in a box. Whether it’s for radio, it’s for DSPs, they feel like they need to know where to play something. Who can we group it with? So that’s always happened. But I don’t really mind it. As long as me, I know that I’m not really tied to a genre. It’s more so my voice, my message, Yeah. That’s it.

jacket. AGRO Studio

string vest. Sona Singh

leather trousers. Auralee

shoes. Martine Rose X Clarks Originals

opposite

jacket. AGRO Studio

string vest. Sona Singh

leather trousers. Auralee

shoes. Martine Rose X Clarks Originals

leather vest. Sona Sing

opposite

faux fur coat + jacket. AGRO Studio

string vest. Sona Singh

leather trousers. Auralee

shoes. Martine Rose X Clarks Originals

I think there’s a broader issue with African music being stereotyped, like Burna Boy mentioned, the term ‘Afrobeat’ is often used to describe all music from the continent, which can lead to artists being mislabeled and the diversity of African music being overlooked. Do you feel that these labels and genre classifications sometimes impact the narrative around African music and artists?

I feel like African music is fairly fresh on the world stage since it hasn’t been popular for as long as some other genres. Of course, it’s been popular in Africa. We understand that not all of Africa makes Afrobeat. But for someone on the outside, it has to be marketed in a way that they understand it. Someone in America might not know that there’s Afrobeat, Afro-soul, Afro-jazz, and Amapiano and that all these come from different regions in Africa. They don’t all come from the same place.

Right now, the most popular African music is Afrobeat, primarily coming from Nigeria, with artists like Burna Boy, Wizkid, and Davido as leading acts. Other artists are emerging who don’t make Afrobeat; for instance, Tems is from the same place, but her music isn’t Afrobeat. Yet, because she’s African, it’s easier for them to label it as Afrobeat.

As an artist, it can be annoying because you’re like, ‘Yo, this is not what I make. I make this.’ If you’re nominated for awards, you might think, ‘I just made an R&B project or a soul project.’ Just because you have a couple of Afrobeat songs doesn’t mean it’s an Afrobeat project or that you’re an Afrobeat artist. It can be frustrating, but you understand that for many of those categorizing this music, it’s all fairly new to them. They’re not ready to create extra genres or awards for African music. It’s as simple as that, so everything is going to be categorized as Afrobeat, whether you like it or not.

What do you have in the pipeline right now? Can you share any details about what we can expect, and where you are headed musically?

I might be inspired by something in a month’s time that sparks a whole project in me. I’m a pretty go-with-the-flow person, always staying true to myself as an artist and my message. Starting in January, I’m going to begin dropping music and releasing a lot next year. I’m just working on finishing the last bits and touches before I put it all out. I want to strip it back, man. I want to think less and go more with my feelings. Now that we have access to numbers, there’s pressure to please radio and get on Spotify playlists. It’s just too much. I just want to release music that makes people feel good and vibe out. Just don’t overthink anything.

faux fur coat. Raphaël Xie

t-shirt. Iceberg History

jeans. Diesel

photography. Maya Wanelik

creative direction + fashion. Kashmir Wickham

talent. Tiggs Da Author

grooming. Simmi Virdee

make up. Shireen Kadhim

art direction + sculpture. Sarah Cotterell

videography. Ray Fiasco

lighting assistant. Alex Galloway

retouch. Lowri Linklater

interview. Afra Ugurlu