Andrew Birkin is widely recognised for his career as a scriptwriter and director; in fact, when we catch hold of him, he’s in the middle of writing a script. But we’re here to talk about his most recent project which delves into another field entirely: photography. With a name like ‘Birkin’ it doesn’t take long to trace the family link to Jane Birkin, his sister, and as a result, Serge Gainsbourg.

Launching today is Andrew Birkin’s book Jane & Serge, published by TASCHEN, comprising a compilation of photographs the young Birkin took of his sister and the French icon, just when he was starting out on his film career. To explain the narrative behind the work, he rewinds back to 1968, explaining how he was working for Stanley Kubrick at the time. It was upon being sent location scouting for Kubrick’s Napoleon project (which never made it to fruition), that he first met Serge Gainsbourg. “I was staying with Jane in Paris, we were staying in the same little hotel, I was doing Napoleon and she was making this movie with Serge. I started taking pictures of – well – him, actually, as well as Jane, soon thereafter, simply because he was an amazing character and was wonderfully photogenic.”

The photographs, he explains, were on the very same Metro Goldwyn Mayer reels that were being shipped back to Britain, for Kubrick to inspect potential locations. “It’s why I had a Polaroid camera, at a time when nobody had one. It had been shipped back from California, along with the stock. One of the perks, of course, was that I could take it home at the weekends, and use MGM’s film.”

Visiting Jane and Serge on a regular basis, Andrew Birkin began to compile volumes of photographs, “For no particular reason, I didn’t really have an end product in mind.” With a wide range of portraits, which include sittings by Jane and Serge, their children Kate and Charlotte, not to mention Nana, Gainsbourg’s dog, the volume of photographs grew to become an intimate exploration of the relation between Andrew Birkin and the subjects he was photographing. He clarifies, however, that he doesn’t consider himself to be a photographer: “I wasn’t sitting there as a photographer, because it’s boring, apart from anything else. You can’t become a participant.”

The two parallel threads – Napoleon and the Gainsbourg portraits – resurfaced simultaneously some thirty years later. Whilst working on the Taschen book Stanley Kubrick’s Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Never Made with editor Alison Castle, the negatives and prints Andrew Birkin had taken of Jane and Serge naturally re-emerged, given that they were interspersed between the Napoleon material. “Because I was photographing Napoleonic sites around France, sometimes I might just have taken a few shots like that, of Jane and Serge on the same roll as Fontainebleau or Versailles.” Spurring him on to compile a book with the portraits, Alison Castle launched Andrew Birkin into the task of sifting through the thousands of snapshots. “I went through all my negatives, which I’d completely forgotten about, or which I hadn’t even printed up, and I put together a paste-up of the thousands of images of Jane and Serge.”

Whilst sifting through the material, which he guesses represents nearly 15, 000 shots, Andrew Birkin rediscovered episodes of his relation with his sister and Serge. “I was amazed, actually, at all the ones I’d never seen before. There was one in particular, the one where Serge is kissing Jane goodbye in the back of a taxi. Jane is looking rather prima donna-ish, aloof.” He relates the story to me, recalling a night-train trip to Paris with Gainsbourg. “Equipped with some rather fine Claret, we traded confessions all night long, but his English wasn’t very good, and my French wasn’t very good: it’s like playing the piano with two fingers, which is sometimes all you need!” Yet, according to him, a pragmatic approach is all you need. “You get to the point far quicker when you’re playing with two fingers, than when you can with the full score.”

With his candid shots and ‘family snap’ style photographs, Andrew Birkin has given us a very intimate view on his relation with two icons of French culture. Talking about Gainsbourg, we discuss the influences, the style and the humour, so particular to the French songwriter. And of course, we turn to Gainsbourg’s desire to uproot, unsettle and unravel the Norm -something Andrew Birkin traces back to wartime Paris, whilst it was still occupied by the Nazis. Being of direct Russian Jewish descent, Gainsbourg was forced to wear his Star of David for the full duration of the occupation. “On the whole, he hid his yellow star with shame.” But his legendary sense of humour, or “exhibitionism,” as Andrew Birkin calls it, was already latent and ready to pounce. “But – this is very Serge – he couldn’t resist occasionally flashing it in front of a group of Bourgeois, just to see the looks of shock on their faces. He absolutely loved to shock. Lots of people love to shock, but they don’t have the talent to go with it.”

With this anecdote, highly representative of Serge Gainsbourg as a whole, we bring the interview to a close. Drawing on an incredibly rich visual legacy, Andrew Birkin’s work is sensitive, intimate and quite unlike anything you’ve seen before.

Andrew and Jane Birkin will be present at the book launch and signing today, November 8th 2013. Click here for more details.

Words/ Patrick Clark

All images © Andrew Birkin/ TASCHEN

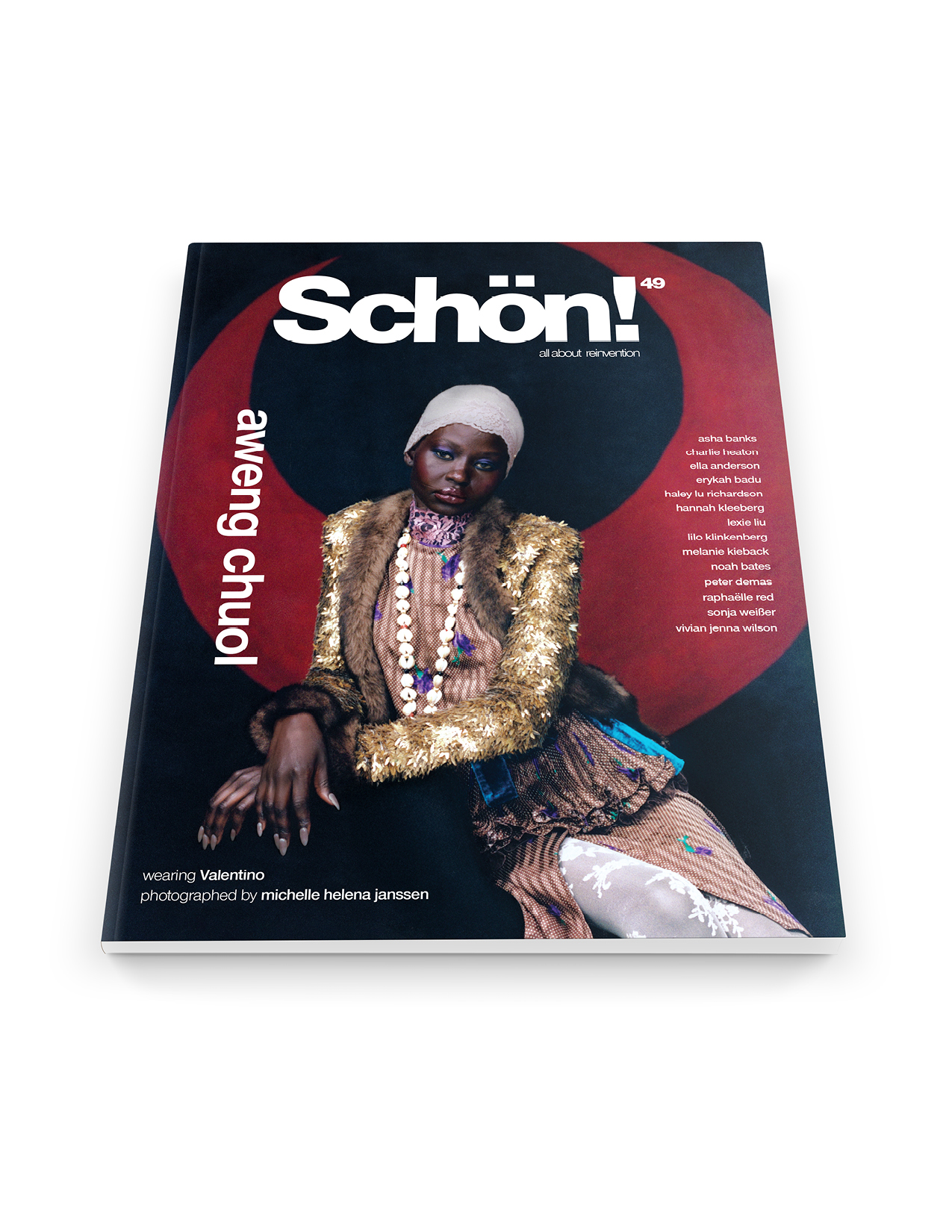

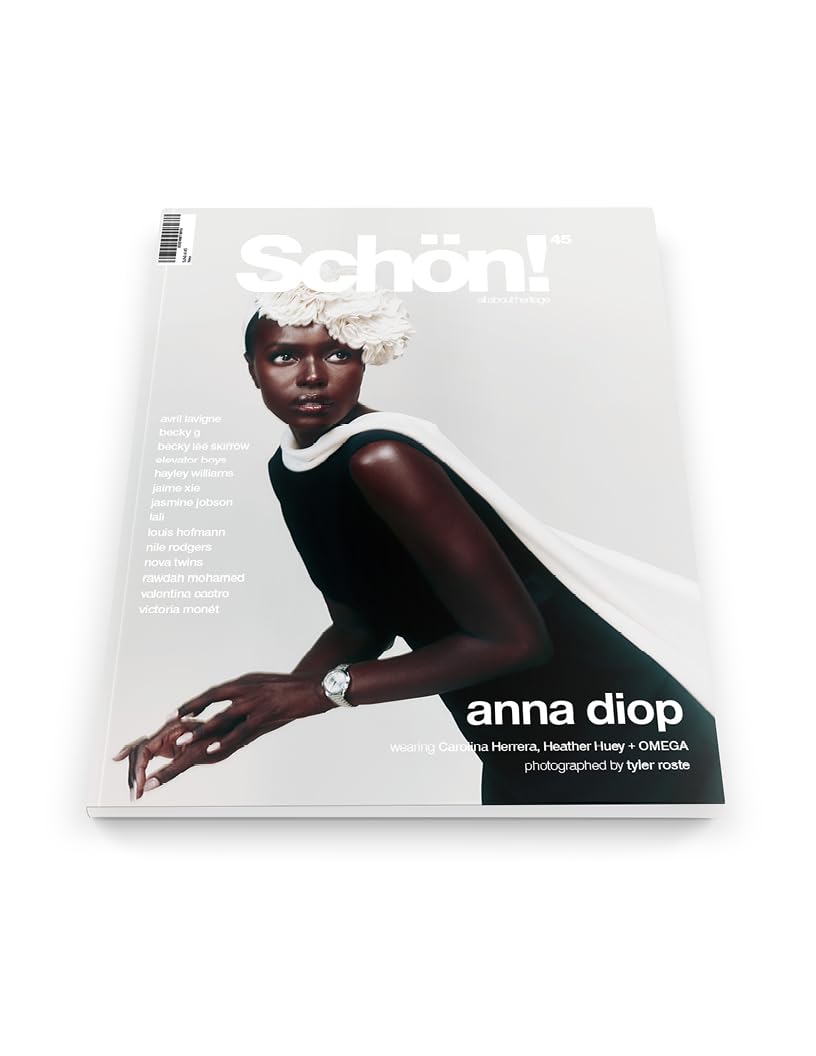

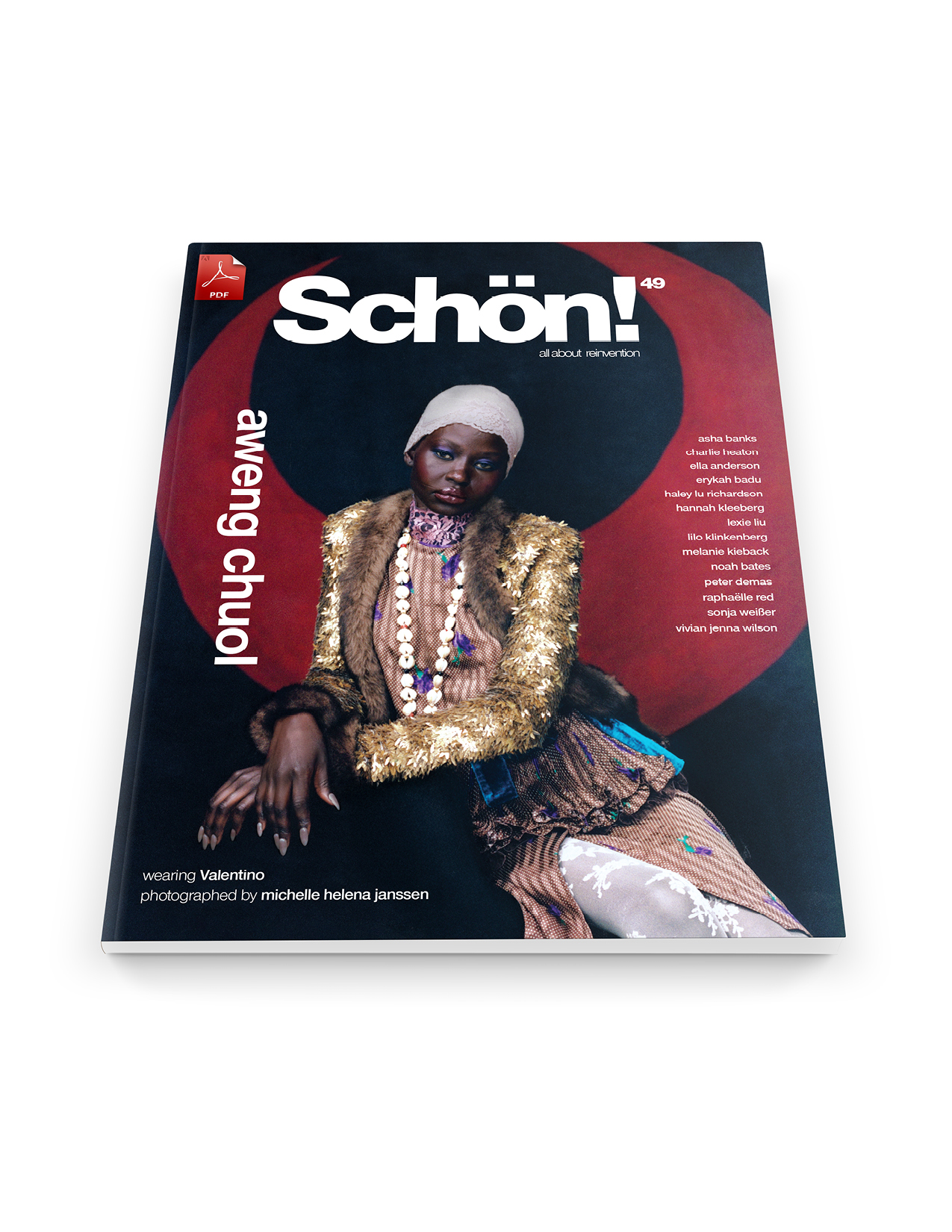

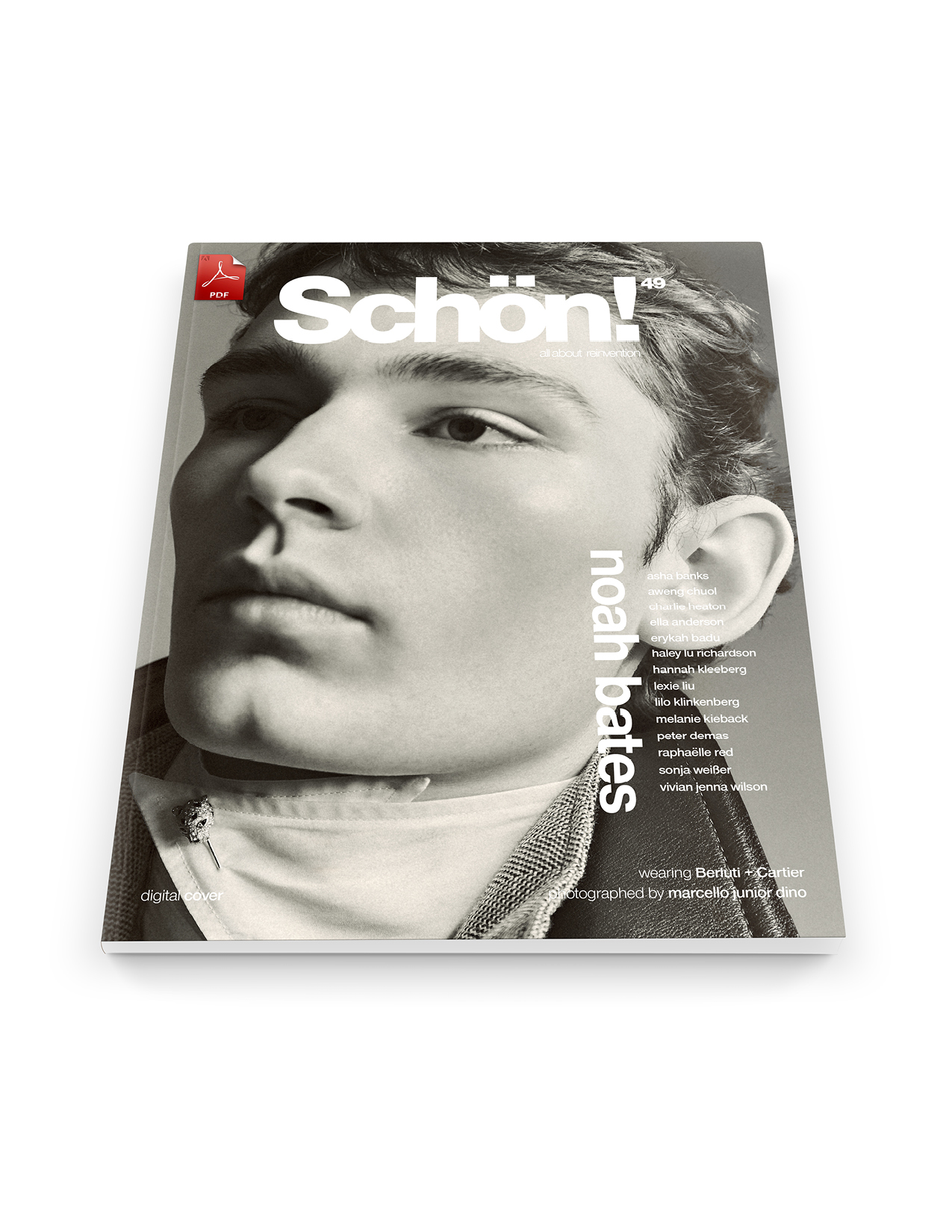

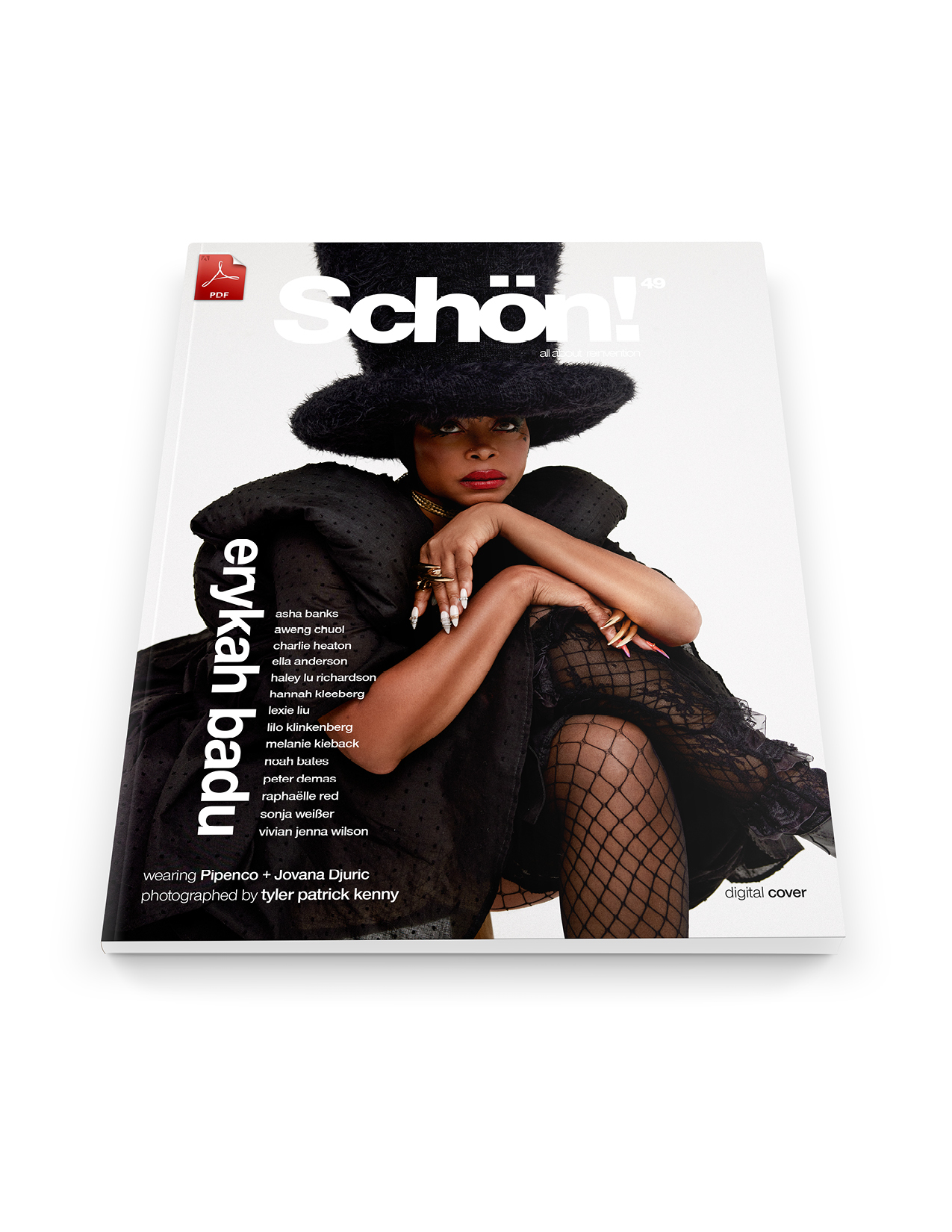

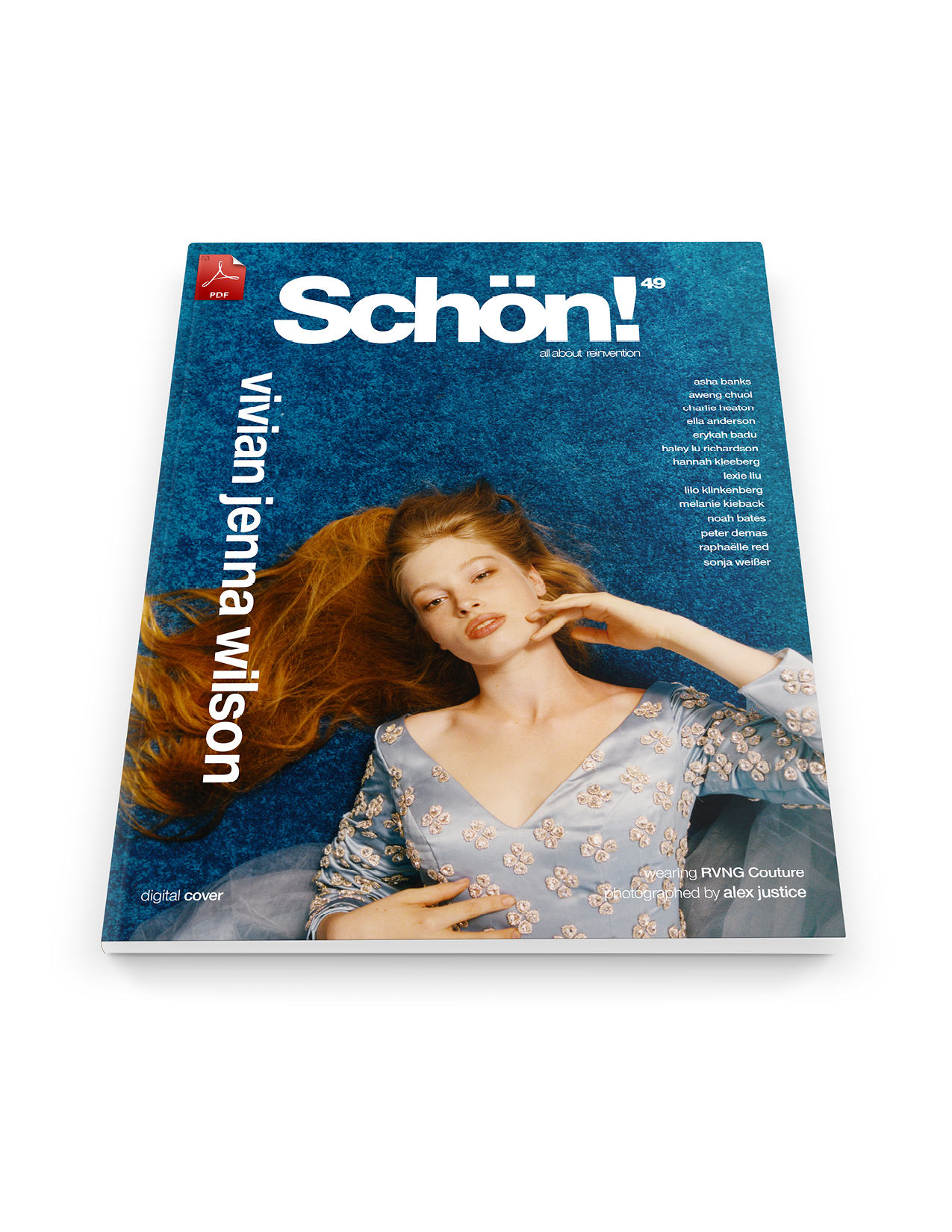

Click the below links to view the newest Schön! Magazine

Download Schön! the eBook

Schön! on the Apple Newsstand

Schön! on Google Play

Schön! on other Tablet & Mobile device

Read Schön! online

Subscribe to Schön! for a year

Collect Schön! limited editions