In 2024, Ruinart is embarking on an artistic endeavour titled “Conversations with Nature” through its Carte Blanche initiative. This initiative brings forth a diverse group of artists deeply committed to nature and driven by their unique talents. While their artistic mediums vary, they all share a profound bond with the natural world. Some explore climate dynamics, others delve into biodiversity. Yet, all endeavour to illuminate the intricate interplay between humanity and nature from their distinct viewpoints. Andrea Bowers merges art with activism, Thijs Biersteker draws from scientific data, Marcus Coates forges connections with the “more than human” realm, Pascale Marthine Tayou uncovers unexpected beauty, Henrique Oliveira crafts striking sculptures integrating plants and organic elements, and Tomoko Sauvage explores the captivating world of bubbles. Chosen deliberately, these six artists will engage in a dialogue with nature in the Champagne region, prompting reflection on our relationship with the living world and embodying Ruinart’s collective vision.

The connection between Maison Ruinart and art stems from the enduring belief that artists possess a unique insight into the world, perceiving what others may overlook. Their evocative creations harbour hidden meanings that possess the power to deeply affect and motivate us. Thus, the Carte Blanche 2024 effectively highlights the symbiotic relationship between artistic expression and the natural world. Over time, these artworks engage in a dialogue, rendering the world more comprehensible. Committed artists, craftsmen, winemakers, and cellar masters join forces, pooling their talents to celebrate beauty in its myriad forms, whether mundane or extraordinary, tangible or imagined.

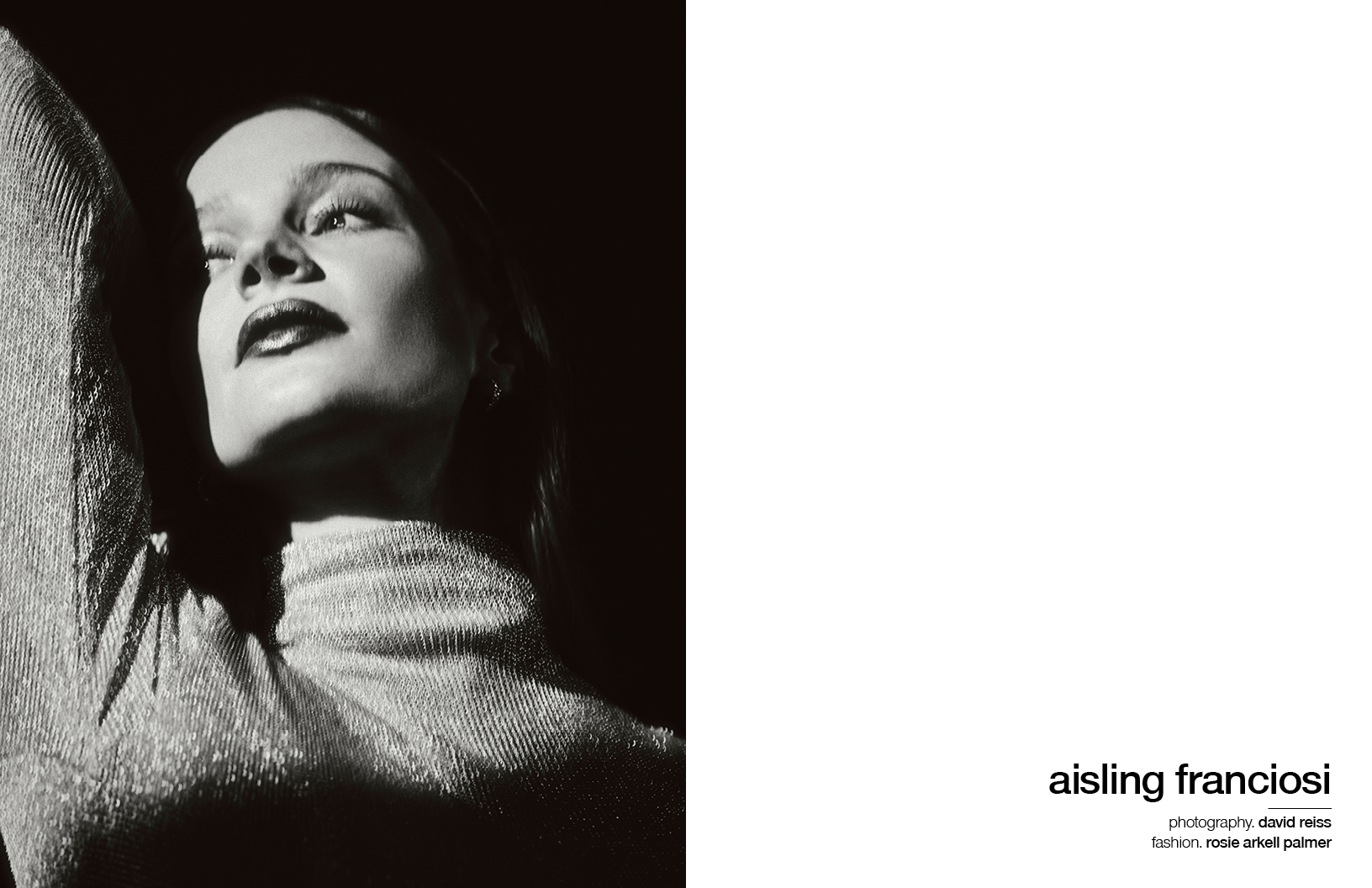

Schön! sits down with artist Henrique Oliveira to discuss his origin story, his work with Ruinart, and more.

What made you move to London instead of staying in Brazil?

I lived in New York before and I was not living in Brazil because around 2007 or 2008 I was traveling regularly. I was spending five months out of the year away from Brazil anyway, so I felt that I needed to have a base or a studio. The first idea was not to move out of Brazil completely but to have a studio outside of Brazil where I could produce, work, and store materials and use as a base for international projects because it is more complicated to send materials from Brazil.

I decided to work outside my home country for inspiration and the desire to have a studio elsewhere. In 2013, I undertook a five-month residency in Paris, where I had a small studio and produced some work, an experience which I thoroughly enjoyed. This stint abroad reinforced my desire to be elsewhere. Additionally, I encountered difficulties shipping materials from Brazil when I was completing a project at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris. A shipment of wood, sourced from discarded materials, was held up in Brazil due to customs issues; they required an invoice despite the material’s negligible value since it was repurposed. This incident highlighted the challenges of relying on international shipping.

Initially, I considered moving to New York, having previously lived in London on two occasions: a year in 2001 while attending art school in San Paolo, and during my teenage years in Cambridge for language school. However, my attempt to settle in the United States was thwarted by recurring visa issues and the associated fees for Brazilian artists. Each time I left the country, I had to renew my visa upon return, as the passport stamp did not align with the three-year validity of the visa. This logistical hurdle coincided with numerous exhibition invitations in Europe between 2018 and 2019, prompting me to consider relocating there.

Given the options of Paris, Berlin, and London, I ultimately chose London for its relatively lower costs, particularly regarding taxes for foreign residents. The UK’s policy of allowing residents to maintain separate tax status for a certain period appealed to me, despite the evolving nature of these regulations. Additionally, London’s status as an English-speaking city offered an opportunity to further improve my language skills, as my previous experiences in English-speaking countries had been relatively short-lived.

Since you have studios in London and Sao Paulo, how do these two places inspire your work?

I don’t know if I get inspiration directly from the places I’ve lived, but there’s a strong possibility. I spent my formative years in a small town until the age of 16, where I had ample contact with nature. We’d swim in the clean river, go camping, and kayaking. Contrastingly, when I moved to São Paulo as a teenager, I found the urban environment stifling. Despite being surrounded by an oppressive atmosphere, I sought solace in nature whenever possible, visiting beaches and mountains on weekends. Upon returning to my hometown, I established my first painting studio and worked there for two years. However, realizing that pursuing art required a move to São Paulo, I relocated to the city to attend art school at São Paulo University. The campus, with its vast green spaces, offered respite from the city’s chaos, making it a comfortable environment for learning.

Interestingly, my initial inspiration didn’t come from nature but rather from the urban environment of São Paulo. As I immersed myself in the art scene, made friends, and explored the city, I found inspiration in its streets and structures. This led me to incorporate found objects into my artwork, influenced by the materials readily available in the city, such as construction scraps and plywood. Working with these materials became a form of collage, reflecting the layers of the city’s architecture and the stories embedded within them. My artistic journey reflects a fusion of urban and rural influences, with São Paulo serving as both a source of inspiration and a canvas for my creativity.

When you hear the words “conversations with nature,” what comes to mind?

As my work evolved, I found myself drawn back to nature, reconnecting with places that held significance to me. This shift marked a natural progression in my practice, influenced by both personal connection and artistic development. Initially, my work was inspired by urban environments, reflecting the textures and colours of city streets. I recall my earliest pieces from art school, where I simply nailed patches of found plywood to walls, treating them like brushstrokes on a canvas. Over time, these works became more three-dimensional, taking on forms reminiscent of trees and organic shapes. This transition was evident in my installations, where I explored the interplay between painterly surfaces and organic constructions. Some pieces focused on recreating the texture of oil paint using dry, brittle wood, while others took on more fluid, organic forms resembling roots or branches.

One significant moment was when I exhibited at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, where my work began to embody these organic shapes more prominently. This shift had been brewing since earlier exhibitions, such as those in Paris and Washington, D.C., where I experimented with transforming plywood into tree-like structures. This ongoing exploration reflects a deepening relationship between urban and natural elements in my work, blurring the lines between industrial materials and organic forms.

How did you get involved with Maison Ruinart?

I’ve been familiar with the art project for quite some time, as I’ve collaborated with the gallery in Paris since my first group show there in 2008. The idea of installing a permanent piece in homes and champagne, a location often mentioned by the gallery, had been floating around since my initial involvement. However, it never materialized due to various reasons. When the gallery extended another invitation more recently, expressing a desire for a permanent installation, I seized the opportunity and agreed to proceed with the project. That’s how it came to fruition.

Once you’ve finished your art piece, what do you hope they take away from it?

I believe that art serves as a vessel for various ideas, both from myself and from those who view it. People often share their interpretations with me, sparking new insights that I sometimes incorporate into my subsequent works. However, I don’t create with a specific expectation of how viewers will perceive it because art is meant to stimulate individual thoughts and perspectives.

It’s interesting how journalists tend to interpret artworks differently from the artist’s original intent. Sometimes, the essence of a piece is simpler than what is perceived by others. Aesthetic ideas or intuitive impulses often guide the creation process, rather than a singular intention. There can be an overlap between the artist’s vision and the viewer’s interpretation, but it’s not always a direct correlation. Each person brings their own unique perspective to the artwork, which can lead to diverse interpretations and understandings.

I read that you had an experience when you were 18 that led you to become interested in art. Can you tell me more about that time?

During my teenage years, drawing was a significant part of my life. However, when I turned 18, I had a profound experience with magic mushrooms. On that day, two friends and I ventured into the fields and gathered a considerable amount of mushrooms, luckily mostly the edible ones. We brewed a potent tea from them, which resulted in a transformative experience for all of us. It was intense, both challenging and exhilarating, like diving into a turbulent yet captivating journey.

Following that experience, I felt a strong urge to express what I had encountered through art. I found myself drawing fervently, seeking to capture the essence of my psychedelic journey on paper. Despite the depth of these drawings, I’ve never shared them with anyone.

How has your experience in nature and childhood influenced what you’re doing now?

Yeah, it’s challenging to pinpoint exactly how my experiences have shaped my perspective, but I believe they’re deeply ingrained in my being. Growing up, I spent time in the tropical jungle near my hometown in São Paulo state, which had a unique ecosystem, albeit different from the urban environment of São Paulo itself. Exploring nature with a biologist friend heightened my awareness of the intricacies of the natural world, from insects to plants.

Interestingly, while my upbringing exposed me to nature, it was during a period of urban living, particularly my weekends in São Paulo, that I felt a shift in my artistic practice. It was amidst the hustle and bustle of city life that I found myself drawn to working with wood, a material inherently connected to nature. This urban phase marked a transformation in my creative journey, leading me to explore the intersection of urban and natural elements in my work. The reconnection with nature, which had initially been overshadowed by urban life, came later, adding depth to my artistic expression.

The artworks by Henrique Oliveira, Thijs Biersteker and Marcus Coates exclusively created for Ruinart will be exhibited during the Gallery Weekend at the “Ruinart Maison 1729 – From Champagne Vineyards to Berlin” at Tacheles (Oranienburger Straße 54, Berlin) from 25th April to 29th April. They will then be presented at art fairs around the world over the course of the year and displayed in the historic garden of the Maison Ruinart in Reims from September.

In addition to the creations of the three artists, inspired by the impressive artistic surroundings, visitors can enjoy a first-class dinner in the Verōnika restaurant and take part in extraordinary workshops – the world of Ruinart, brought to life in Berlin.

Learn more about Ruinart’s “Conversations with Nature” series at Ruinart.com.

interview. Kelsey Barnes