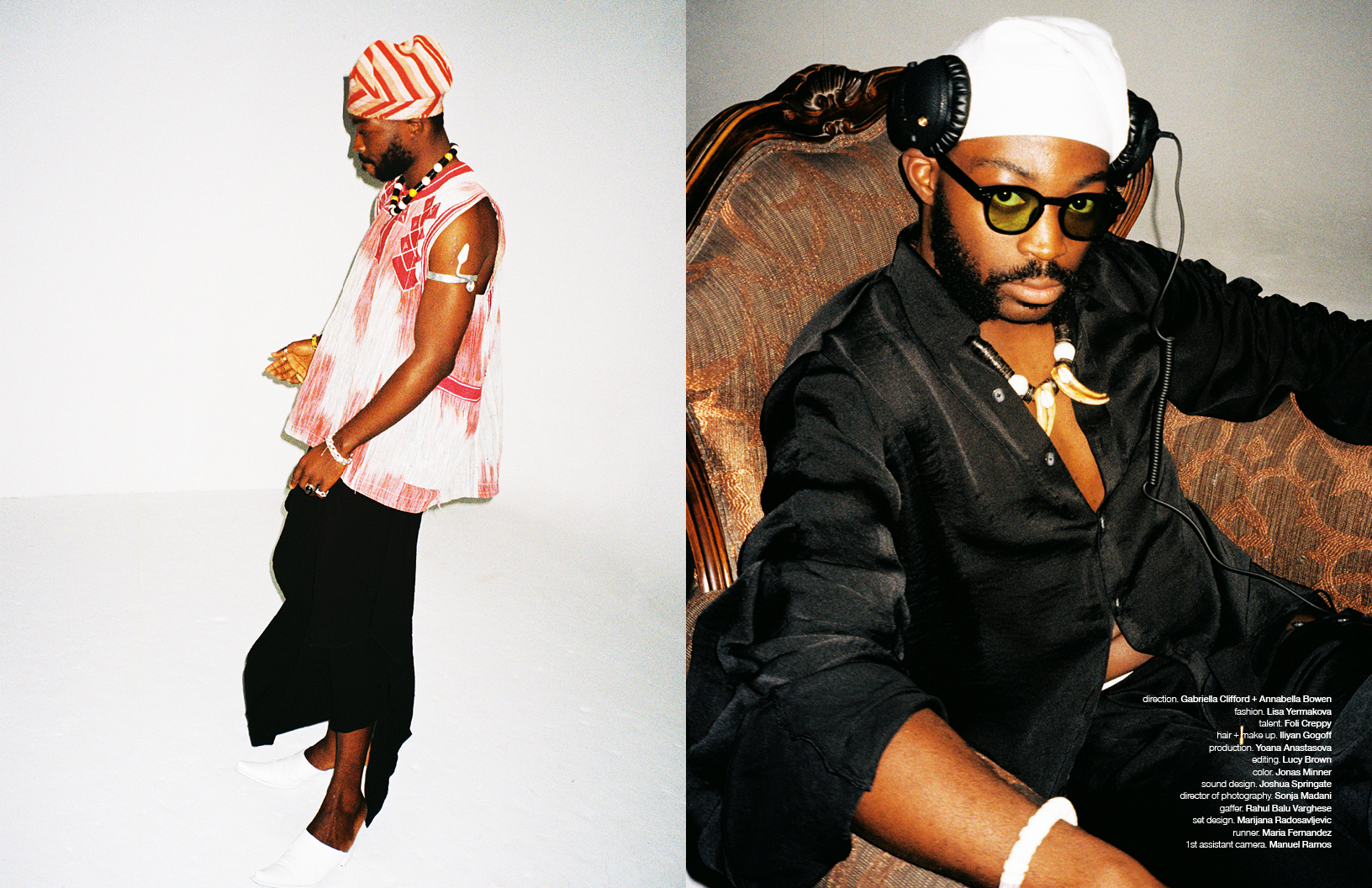

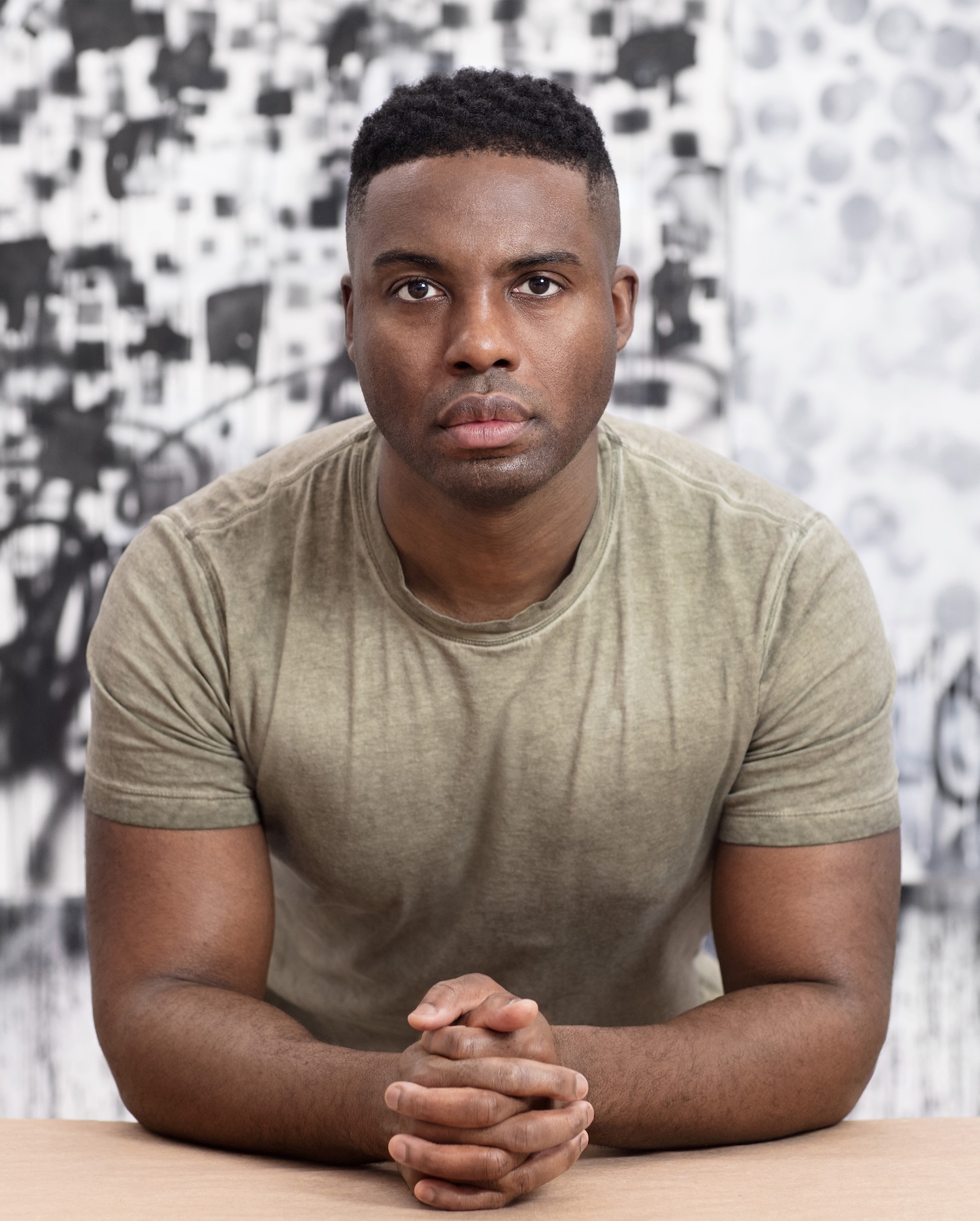

Sofia Coppola, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

The art we consume is dreamed up of visionaries and, in turn, the art they create shape our worldview. After a summer of ‘girlhood’ centric art and the term being thrown about over social media, it’s integral to note one filmmaker who has been shining a light on the myriad stages of womanhood for years: Sofia Coppola.

For over two decades the celebrated filmmaker has showcased and celebrated the intricacies of growing up as depicted in The Virgin Suicides to her own view of celebrity culture and wealth, as seen in The Bling Ring. Her own cinematic universe opened a world for young people who first were exposed to her films through social media and blogs to gain an interest in film. Now, with the release of Sofia Coppola: Archive published by MACK, everyone can dive into Coppola’s creative process.

At the start of Archive, Coppola talks about the collection of trinkets and mementos she ends up gaining once one of her projects wraps. From notes to photos to scripts, the collection turns into a kaleidoscope of Coppola’s career — a true archive of her work as a filmmaker that readers and film lovers alike now get to indulge in. The extensive look of her career spans across all of her feature films, beginning with the cult classic The Virgin Suicides to 2023’s Priscilla, including everything from Polaroid images from sets to screenshots of emails sent by Presley herself.

Leaning entirely on Coppola’s artefacts as the driving creative force behind the book, Joseph Logan and Anamaria Morris incorporated splashes of pink, the director’s favourite colour, to tie all the sections together. The start of Archive includes a moving interview with famed film journalist Lynn Hirschberg to who Coppola says: “Across all my films, there is a common quality: there is always a world and there is always a girl trying to navigate it. That’s the story that will always intrigue me.”

Edited and annotated by Coppola, Archive is a dream realised for both the filmmaker and her devoted fans. Now, rather than dreaming of what it must be like to be inside Sofia Coppola’s mind, they can see it for themselves.

Sofia Coppola, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Sofia Coppola, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Sofia Coppola, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Sofia Coppola, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Sofia Coppola, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Archive (2023) by Sofia Coppola, published by MACK, is available now.

imagery. MACK

words. Kelsey Barnes