Slava Mogutin’s trajectory, be it personal, cultural or political, is one that defies conventions. From an Orthodox adolescence in Soviet Russia to a short-lived career in porn, and with a career that blurs lines of all sorts – social, cultural, corporeal –Mogutin’s work is indecipherable if read through a heteronormative lens. It takes a queer pair of specs to penetrate the masses of bodies, humectant skin and fetishistic imagery – to unveil a narrative of intimacy, sexuality, explicit scenes, love: queer identities exposed through the contorted, restrictive dynamics of oppression. Celebrating life beyond vulnerability, Schön! sits down with Slava Mogutin to analyse the process of creative catharsis: a process which confronts personal and collective, East and West; that pits mediums against one another, and frees the body from the yoke of straight capitalism. With a career that’s seen him team up with Allen Ginsberg, Dennis Cooper, Gilbert & George and Marina Abramović, to name a few, Slava has a tale to tell.

The multimedia nature of your work is particularly fascinating – how did you come to combining so many practices? Does one hold a particular place in your work?

I started writing poetry and journalism in my teenage years and when I moved to Moscow I supported myself by working as a reporter and editor for the first Russian independent newspapers, publishers and radio stations. Around the same time I was already exploring photography, performance and film. I was always interested in multimedia art that combines different genres and mediums and involves both parts of my brain. And I was always unapologetically queer about my own identity and point of view, writing on gay issues at the time when it was still taboo in Russia. When I was forced to leave my country and moved to New York, visual art became my main passion and medium, although I remain a poet in everything I do.

How did your interest in photography begin? Was there anybody who influenced your photographic style?

Before I left for Moscow, I borrowed (or stole rather) my father’s old trusted FED-3 camera and started documenting my world by taking pictures of friends, underground rock concerts and crumbling Orthodox cathedrals. I got baptized at the age 16 and was deeply religious at the time, but it’s fair to say that my work was very unorthodox from the get-go. It was a reflection on my sexual identity, underground subcultures, post-Soviet symbolism, and Orthodox mythology. I was very much influenced by Alexander Rodchenko, one of the pioneers of Soviet photography, his fearless documentary style and incredible photo montages and graphic design experimentations. I always wondered what his work would look like if he had access to colour photography, and his powerful austere aesthetic still inspires me to this day.

Your poetry seems to focus on the workings of the fascist behavior towards non-conformative beings or queer sexualities. With a difficult and oppressive adolescence in Russia, what part does the personal play in your work?

All my work comes from a personal place and experience. Considering the hostile homophobic environment I grew up in, I think it’s only natural that I wanted to explore the alternative modes of human nature and sexuality. At school we were taught how to operate tractors and machine guns instead of our own bodies or brains. Our bodies simply belonged to the Soviet Union, we were just tiny screws in that giant totalitarian machine, and it left a stark and damaging impression on my adolescent years. Then I spent the rest of my life reclaiming my body and studying others.

What do you think the importance of individual action (such as your action of getting married with Robert Filippini despite the obvious risks) is when facing institutionalized homophobia and violent oppression? Where does the limit between individual and collective action lie?

At the time when Robert and I tried to officially register our marriage, it wasn’t yet legal anywhere else in the world. Robert was a member of Queer Nation and the founder of the first Russian-American AIDS support group. He was also someone who introduced me to the work of many important queer figures, such as David Wojnarowicz, Derek Jarman, Bruce LaBruce, and Gus Van Sant. Back in the early 1990s, there was only a small network of gay activists and entrepreneurs in Moscow and St. Petersburg, we all knew each other and tried to contribute all we could to the common cause. Robert and I felt like it was an important moment for such a symbolic and personal gesture as attempting to register our Russian-American union. Much to our surprise, we got permission from the first consul of the US embassy in Moscow. And even despite the fact that our marriage was rejected by the Russian officials, we were successful in bringing international attention to the issues of gay rights in my country. In recent years our action inspired several other gay and lesbian couples to make similar attempts, and I do hope that same-sex marriage will become legal in Russia in my lifetime.

In line with this, you were the first Russian to be granted political asylum for homophobic persecution. Does the exile still hold its weight? How did you deal with such a traumatic event? What importance did this event have in your life, in the lives of others?

Being exiled from my native country was obviously a traumatic, life-changing experience that shaped my personal and artistic identity. My last few years before the exile were poisoned by homophobic persecution, day-to-day police surveillance, death threats, and media harassment. I couldn’t imagine that I would make so many enemies by simply being openly gay but that was the reality of my situation and I had a choice between fighting to my death in the Russian jail or escaping and starting my life and career all over again in the US. My asylum case consisted of hundreds of pages and gathered support of all major human rights groups. Most importantly, it opened the door to many cases of other gay refugees from Russia and former Soviet republics. Without a doubt, this flood of refugees only increased in recent years, with the adoption of the infamous “gay propaganda” law, which essentially prohibits any public expressions of homosexuality.

How can you contextualize current political and social situation in Russia now? Do you see any evolution in the situation or any chance for change?

I’m always following the Russian news and unfortunately I don’t see any evolution or improvement in sight, as long as Putin’s corrupt authoritarian regime is in power. Putin is the new Tsar who sees his mission in reasserting Russia’s role as a global superpower, even if it comes at the expense of free speech, free press and individual freedoms. That said, his popularity is just as high now as it was when he first took office back in 2000, thanks to the fact that most Russians see him as a strong, sober and patriotic leader, as opposed to his predecessor, the drunken buffoon Boris Yeltsin, who was perhaps the most corrupt leader of Russia ever.

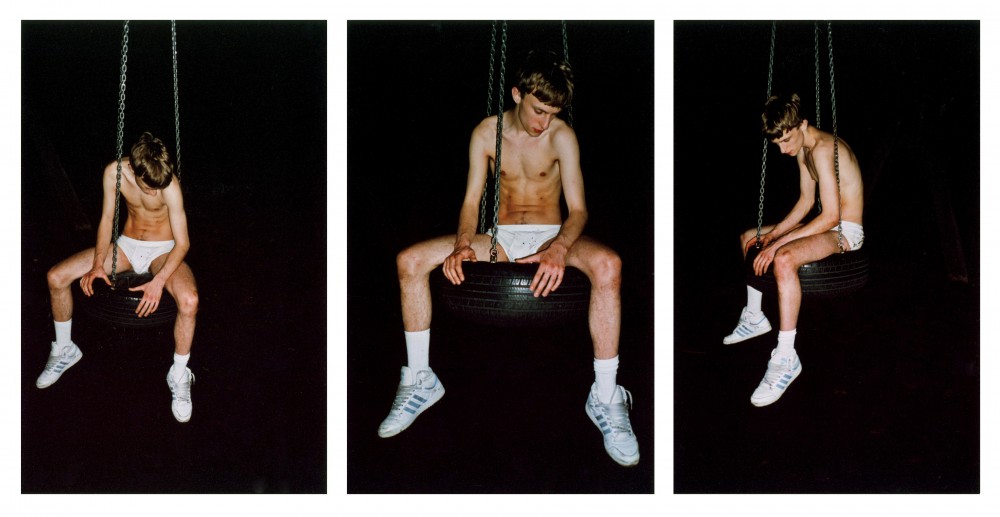

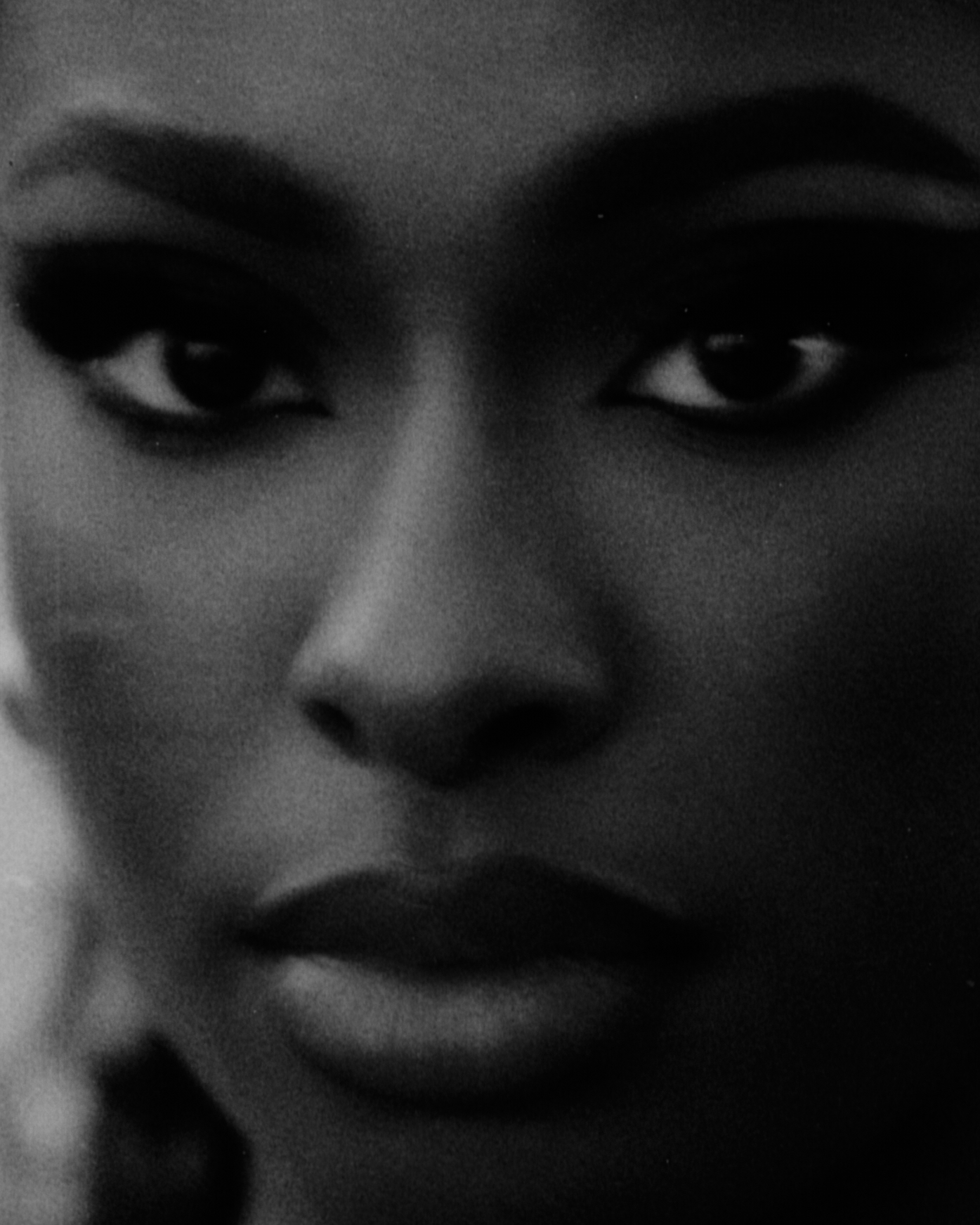

Your work recurringly addresses both the vulnerability and the violence exerted on the male homosexual body. Where did your fascination for capturing male bodies, in interaction, alone, come from?

Perhaps, this fascination came from the Soviet schoolbooks depicting homoerotic paintings of young uniformed men in various stages of undress and stories of tortured young pioneers and partisans. I believe that Soviet propaganda had a strong homoerotic undertone, so no wonder those mythical heroic stories and images had triggered my creative imagination and sexual awakening. Torture and pleasure, submission and domination, loyalty and betrayal, crime and punishment, love and hate—those were the ideas that occupied my mind from an early age. All the brainwashing aside, I think there was something very romantic about growing up in that paramilitary environment and being a part of the collective Communist Utopia—just waiting to turn into a giant circle jerk of uniformed guys. I must admit that to this day I find uniforms of all kinds very appealing, and the role-play that comes with them.

Do these practices exist as a personal, collective catharsis?

From my personal and artistic experience, many people in the fetish and S/M community find their particular fetishes and sexual practices very liberating, empowering and all-consuming. It’s something more than a lifestyle; it’s a religion, dogma. I suppose, like any other religion, it can offer you salvation or eternal punishment, depending on what you’re looking for.

Where does the power of performance reside? What does the involvement of your own body entail in your works?

Performance is perhaps the most immediate and effective way of transmitting your creative juices and ideas into the universe. When I do live performances I often think of my body as a vessel for higher power and purpose—it’s a feeling that gives me goose bumps and a huge adrenaline rush and makes my hair stand on the back of my neck. Moments like that are sure worth living for!

You’ve previously mentioned a failed career in pornography – now your work continuously seems to address a recording of social, political and cultural histories/stories of sexuality. What role does sexuality and sex play in your life and work now?

Yes, it’s a true story—I was disqualified first as a porn actor and then as a photographer. I used to shoot for magazines like Honcho, Inches, Playguy, and Playgirl, and my editors would always complain that my pictures were too hardcore or too soft, too humorous, or didn’t contain enough hard-ons. I guess I was never as phallo-centric as other photographers shooting for them. I think the attitude towards porn is a good indicator of how progressive our society is. At the same time, porn reflects and challenges certain social norms and moral stereotypes that shape who we’re and what we consider acceptable or obscene. These perceptions have changed throughout human history and now it seems that we enter the period of new Puritanism, with the Internet censorship on the rise and nudity being perceived just as dangerous as it was in the good old Victorian times. I use nudity and sexual imagery as a weapon against censorship and hypocrisy. I’m more concerned with dissecting this outdated notion of sexuality and masculinity and showing an encompassing spectrum where sexuality takes many different shapes and forms.

Your collaborators are numerous and varied – Bruce LaBruce springs to mind – what do collaborative narratives include that others don’t? Does power still reside in collectivity?

I’m always inspired by the work of my fellow artists and drawing on the energy we create together. I was fortunate to work with some of my heroes, including Allen Ginsberg, Dennis Cooper, Terry Richardson, Gilbert & George, Marina Abramović, Michael Stipe, and, most recently, Edmund White and Susanne Oberbeck of No Bra. I do believe in the third creative mind activated by letting go of your personal ego and limitations.

With exposure through social media and other digital media, do you believe the new generation Russia is more accepting, liberal, open? What role does the Internet play in regard to the young generation of queer Russians?

Internet is perhaps the only refuge and safe place that Russian queers have today, since they still have very little visibility and acceptance in the mainstream society. I do think that the new generation of Russians is more open-minded and tolerant since they get to travel more and experience other cultures—something that very few people of older generations were able to do before the fall of the Iron Curtain.

Earlier this year, you were seen walking in Hood By Air’s Fall/Winter 2016 fashion show. Have you followed the work of Shayne Oliver in the past?

Shayne and I go back. We met some years ago at the time when I was working on my book NYC Go-Go. He is one of my favourite DJs and his shows always remind me of the good old clubland days. The theme of Shayne’s latest Pilgrim collection is refugees and it’s something that I could strongly relate to, thanks to my own refugee experience. I wanted to support him because I think it’s important for artists to make a statement on this issue at the time of the worst refugee crisis since World War II and the rising xenophobia and chauvinism in the US and across Europe.

With Shayne Oliver being one of many who is creating a new wave in fashion, breaking gender lines and introducing queer imagery and bodies into a public space – does fashion still have the potential to queer norms? Do queer bodies have a place in fashion that they didn’t previously have?

I think fashion is finally fully embracing its queer roots by giving more attention to the queer, transgender or gender-neutral body, without playing the traditional macho game. It’s remarkable how the fashion ideals of male beauty and masculinity have changed over the last 20 years, from a beefcake to an androgynous anorexic boy with long hair. I’m convinced that the future of humankind is gender-neutral and fashion has a special function in this Universal Transitioning.

What projects are you currently working on?

I’m putting together several new book projects, including a book of poetry comprised of spam and a book of photography covering over a decade of my studio and magazine work.

Discover Slava Mogutin’s work here.

Words / Patrick Clark

Follow him here.

All photography and works courtesy of Slava Mogutin ©

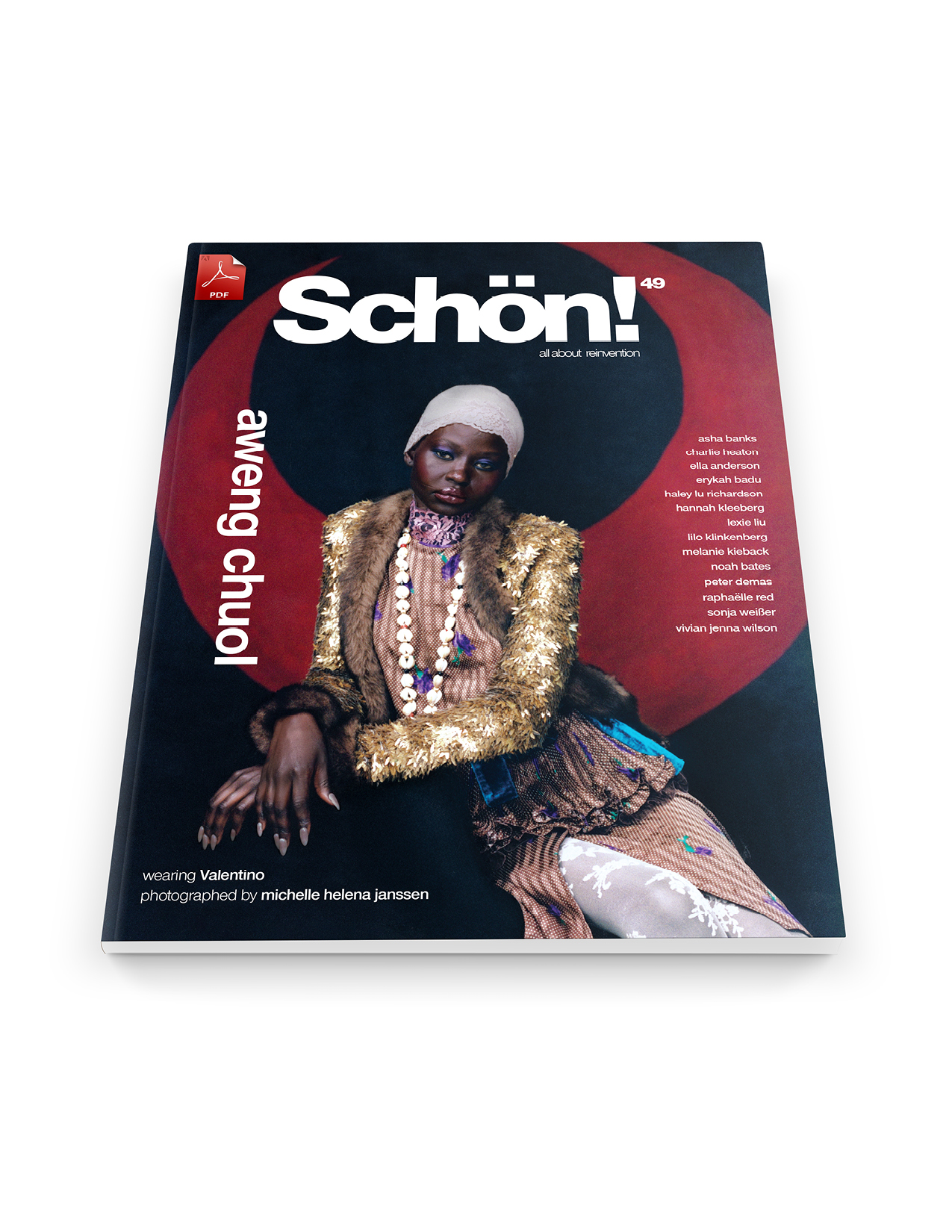

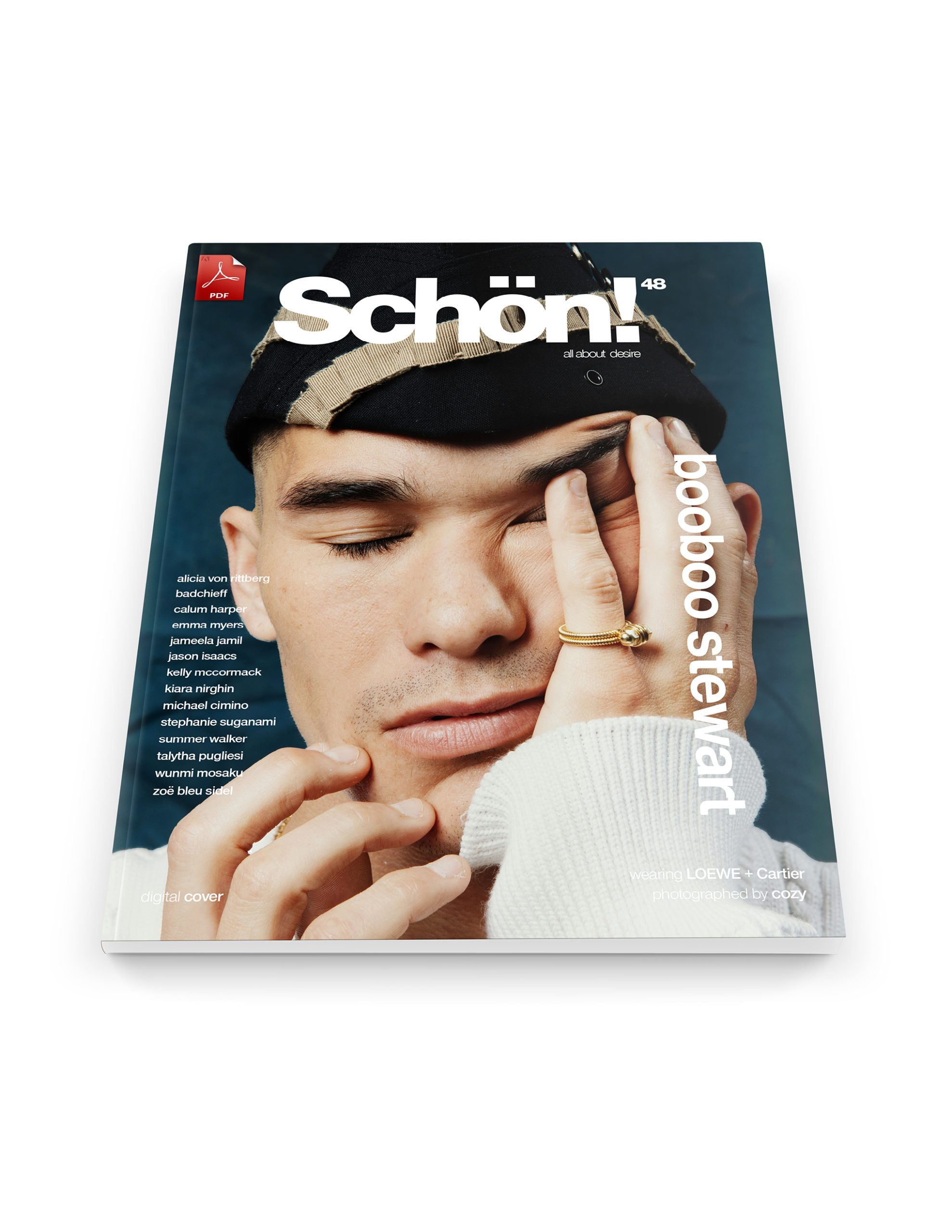

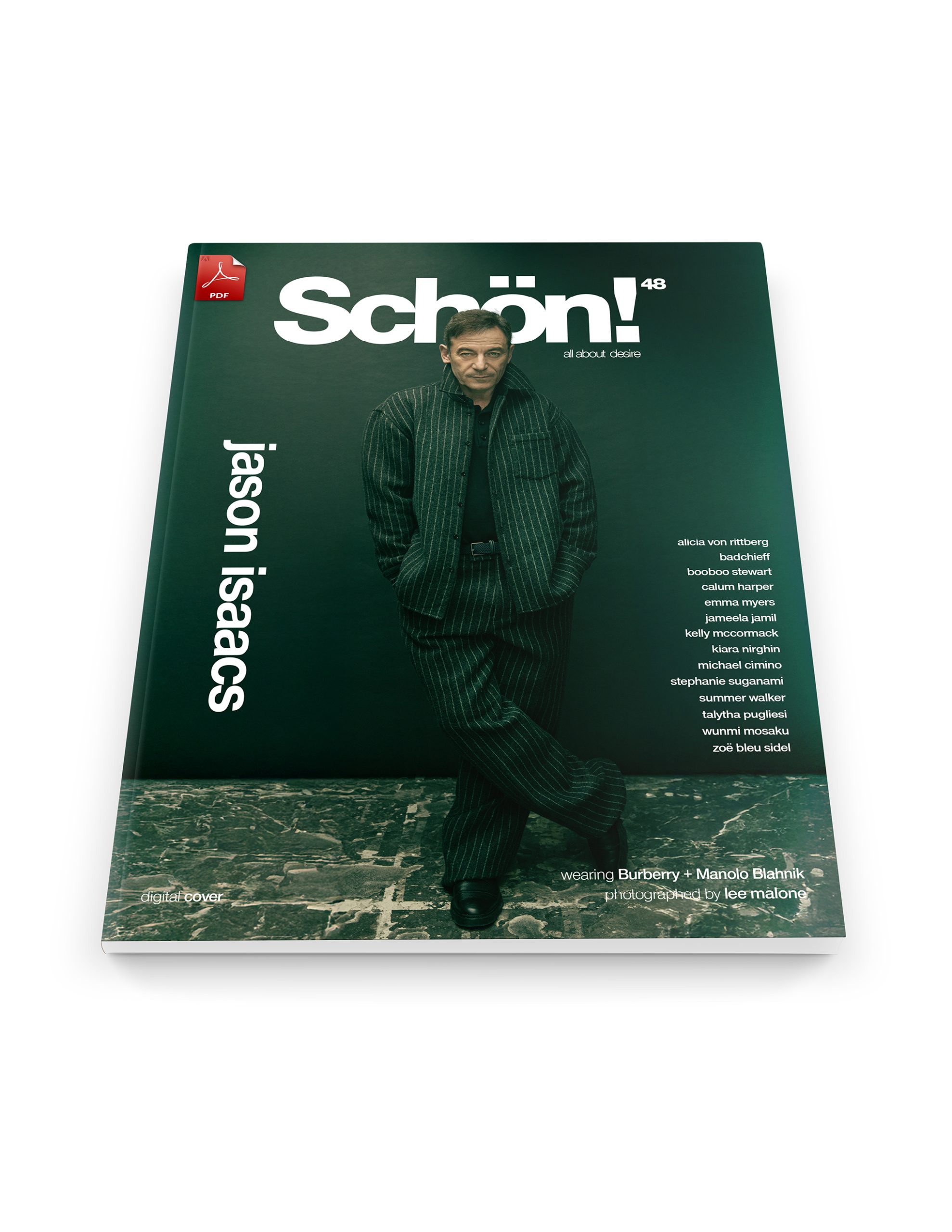

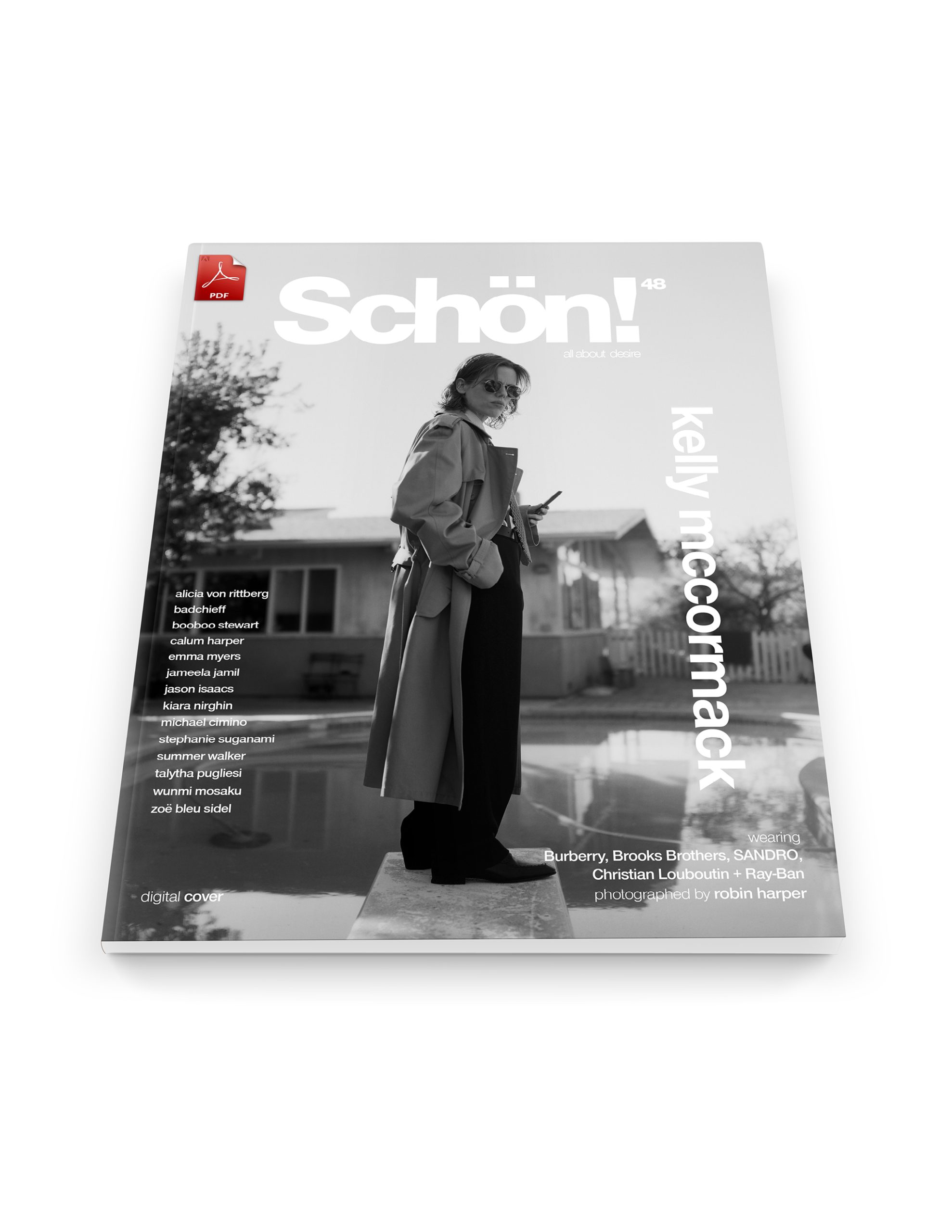

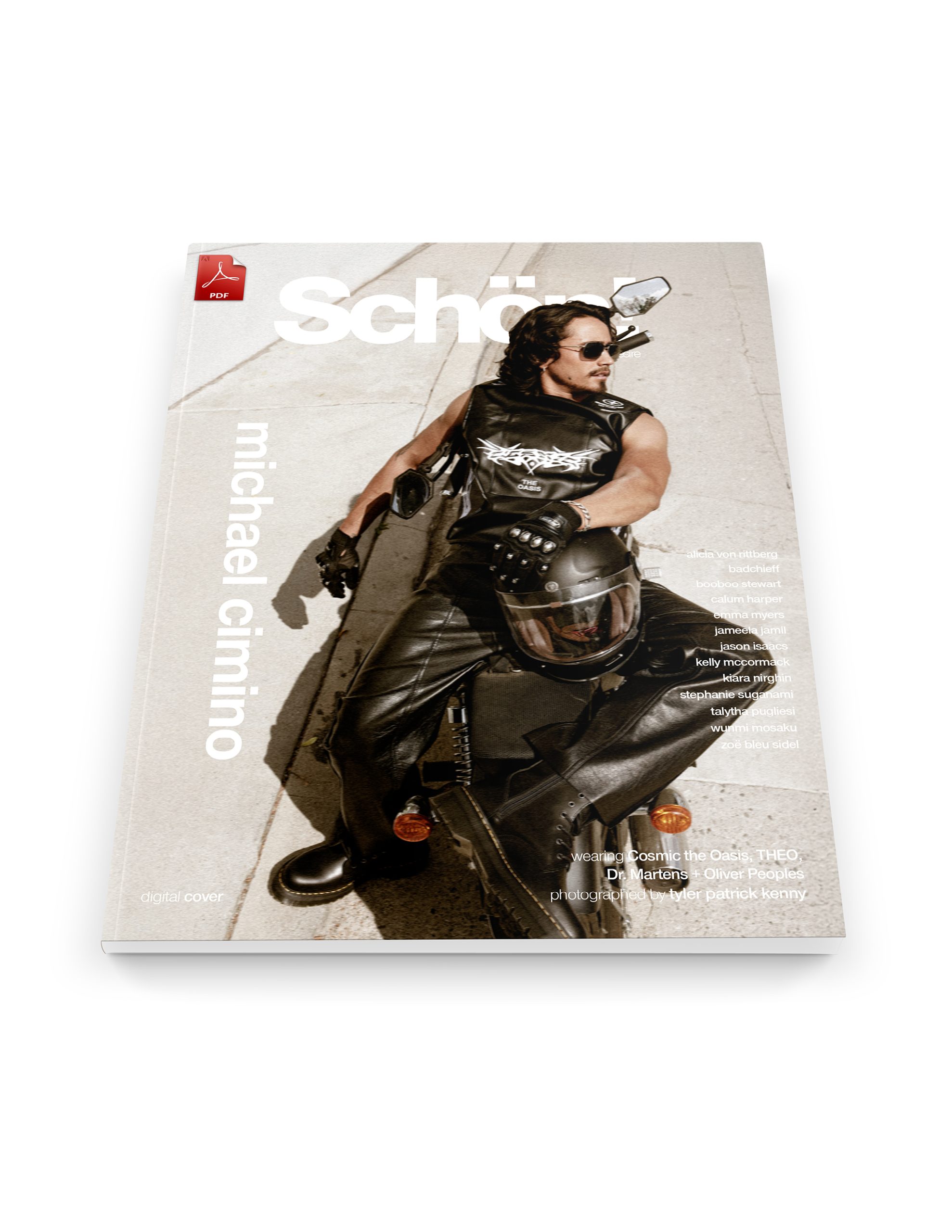

Discover the latest issue of Schön!.

Now available in print, as an ebook, online and on any mobile device.