When we meet artist Thomas Lélu at Café Etienne Marcel, a retro futuristic Parisian brasserie, Lélu beckons the waitress and orders, “Un moelleux au chocolat s’il vous plaît.” With this, we start our conversation. Growing up in Brittany, France, Lélu started drawing at a very young age. From there, he transitioned into painting, and continued the practice all throughout his teenage years. He entered École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs with the intention of studying classical painting. While it was clear he wanted to pursue what he had already been doing for a large portion of his life, Arts Décoratifs provided opportunities elsewhere. “I discovered a lot of other alternatives such as visual communications, graphics, design, and photography,” Lélu says. “I think I was getting bored with painting, since I already had a formation in it. Painting is very solitary, and I’m not projected as a solitary individual. Suddenly, there was something much more open, and I was deeply interested in artists who had training in applied arts.”

Some of those artists include Pierre Huyghe and Pierre Bismuth, whose analysis of imagery stimulated Lélu. From painting, Lélu deviated towards a practice that was more linked to commentary on images. There was a more conceptual dimension, more linked to reinterpretation.

One example is Lélu’s art series Hide and Stain, which features images of women from ’70s men’s magazines. He splashes paint on women’s bodies and scribbles on their faces. Using the feminine figure as a principal subject, his first objective was to conceal a part of the body. “I wanted to hide the most charged part, whether erotic or emotional. On one hand, it’s a pictorial veil, and on another, it’s a game of transparence. In a certain manner, the paint acts as clothes. I was constantly uncovering and discovering,” Lélu explains.

The mixed colours act as a language – a sort of poetry. The colours are reminiscent of a cocktail. It’s a rendition of variation on an image that is in itself very brutal and frontal. Lélu generates a form that has its own identity; the painting almost makes the image three dimensional in volume, like a sculpture. In the global manner, however, Lélu looks to the individual who is not trained in art. “The amateur practice is doing something without intending to make art. I am interested in people who are not artists. I find that it’s rare, and all that is rare is precious,” Lélu describes.

After spending several enriching and fun years as the Creative Director of French Playboy and Artistic Director of Citizen K, more than anything, Lélu extracted literary influence from these jobs. He has written books and novels, and claims that his work is not related to fashion. “It’s more fashion that is interested in my work, Lélu articulates. “I remember the first time I entered Colette – I found it horrible. It scared me; I was aggressed by it. When I had my first exhibition and published my first book, Colette proposed me to create something for their storefront window. I didn’t understand, but I had fun with it.”

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Lélu’s work is that each series he churns out is more innovative than the last. He most recently worked with printed images on car bonnets, a retake on the book La Persuasion Clandestine. The dimension of camouflage and concept of image sculpture motivates the artist. “What interests me in a reoccurring manner in most of my work is the question of perception,” Lélu enlightens. “That, and I have a lot of fun on Instagram where I put objects on images.”

Art is a daily process. Lélu accumulates notes everyday and jots down his ideas left and right. At a certain moment, the ideas begin to naturally take shape. All of a sudden, it’s evident. It’s the right moment and the correct context. “It’s an ensemble of elements. It often comes from a discussion. I really believe in meetings and dialogues in the creative process. One needs to be available; the mind and spirit have to let things come,” Lélu smiles. He further explains that contrarily, the artist can conceptualize the idea through a “spark.” Ideas materialise on their own, but it happens through practice. “You have to be in contact with the material,” Lélu elaborates. “There’s a given moment where letting go has influence in the creative process. We heighten the concept to another dimension. That’s something about sensitivity and sensuality.”

“Often, ideas and projects come out of the conversations. For me, the dialogue is one of the principal elements in the creative process. There’s something in the art of immersion. There’s a barrier between the atelier and real life. I really believe in this exchange. I can’t stay locked up in my atelier nonstop. I immediately have a pressure that drives me in circles.”

Because Lélu has an outside job, he does not feel pressured when it comes to art. Art and work are two distinct things for him. “In relation to creation, this allows me to create without being dependent on money,” Lélu explains. “I like to be linked to the normal world. It doesn’t interest me to only rest in the world of art. Art for art is something that turns around itself.”

To see more of Thomas Lélu’s work, click here. For his Instagram, click here.

Words / Sheri Chiu

Follow her on Twitter.

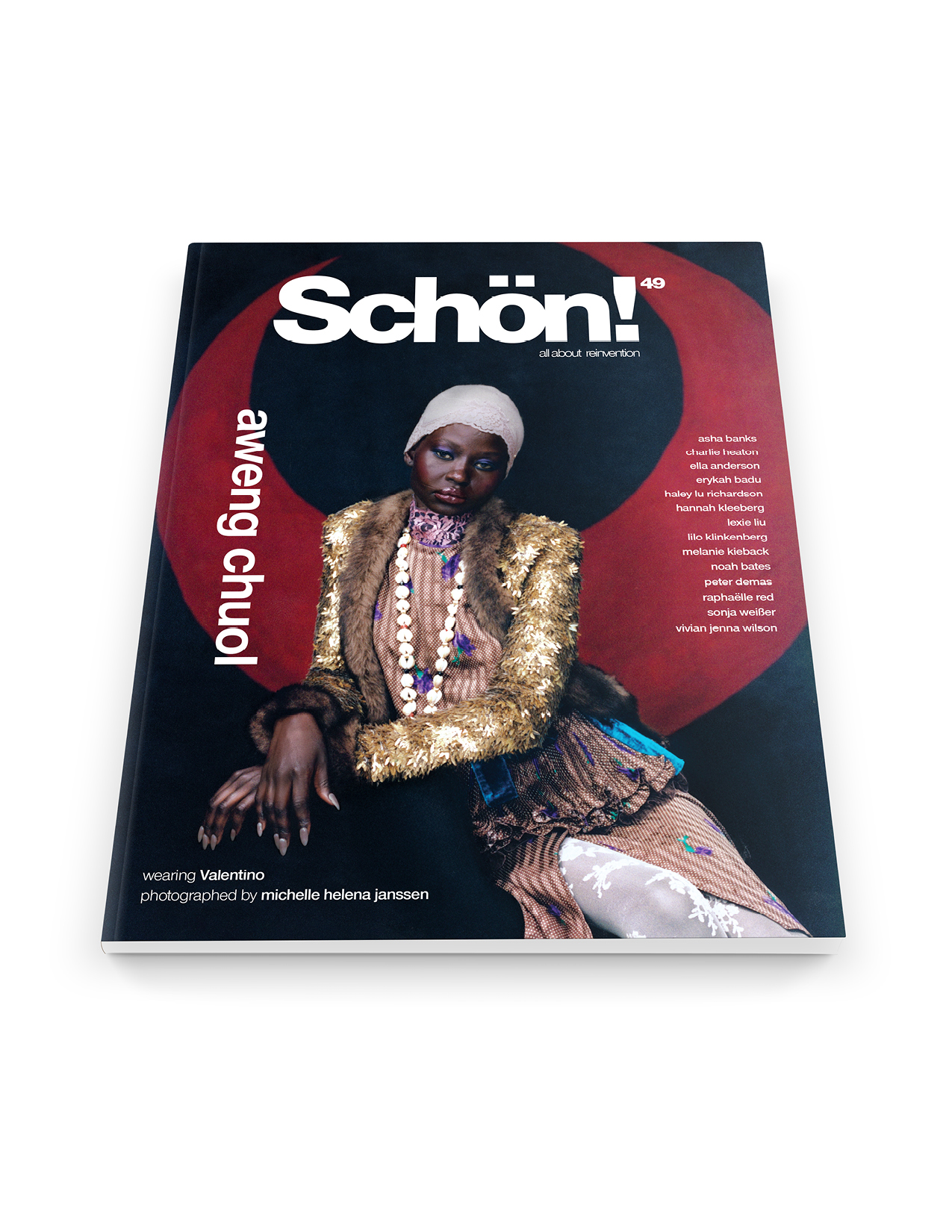

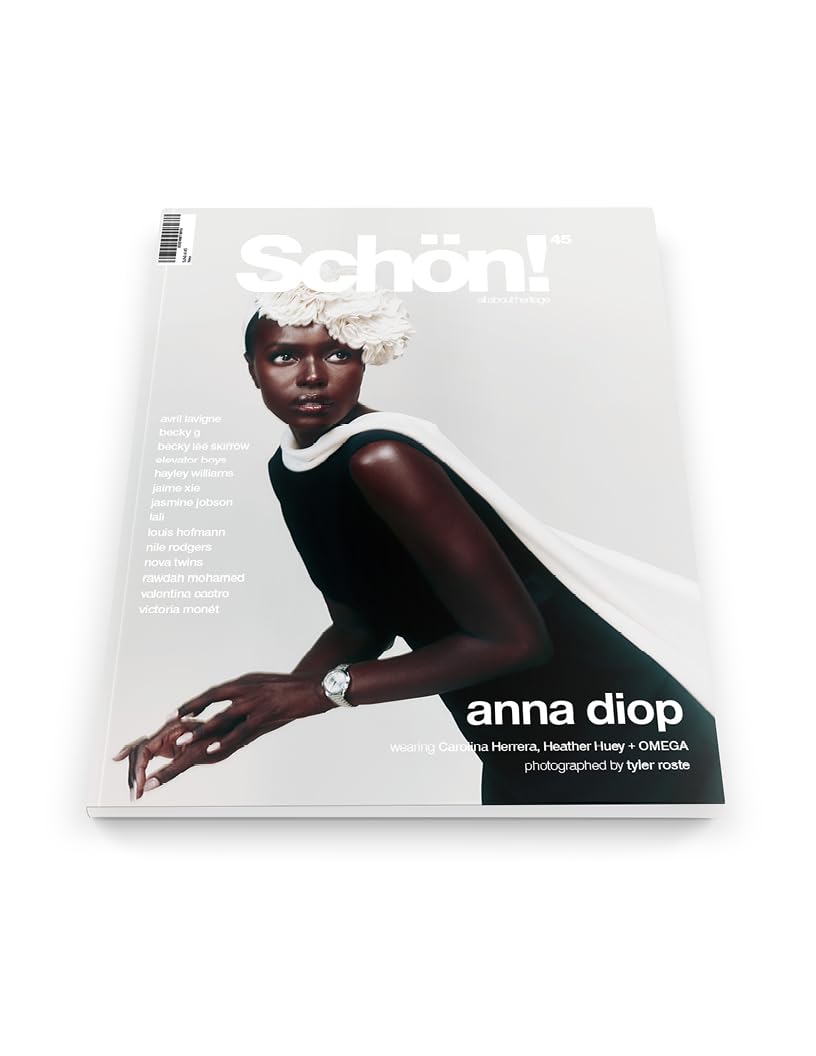

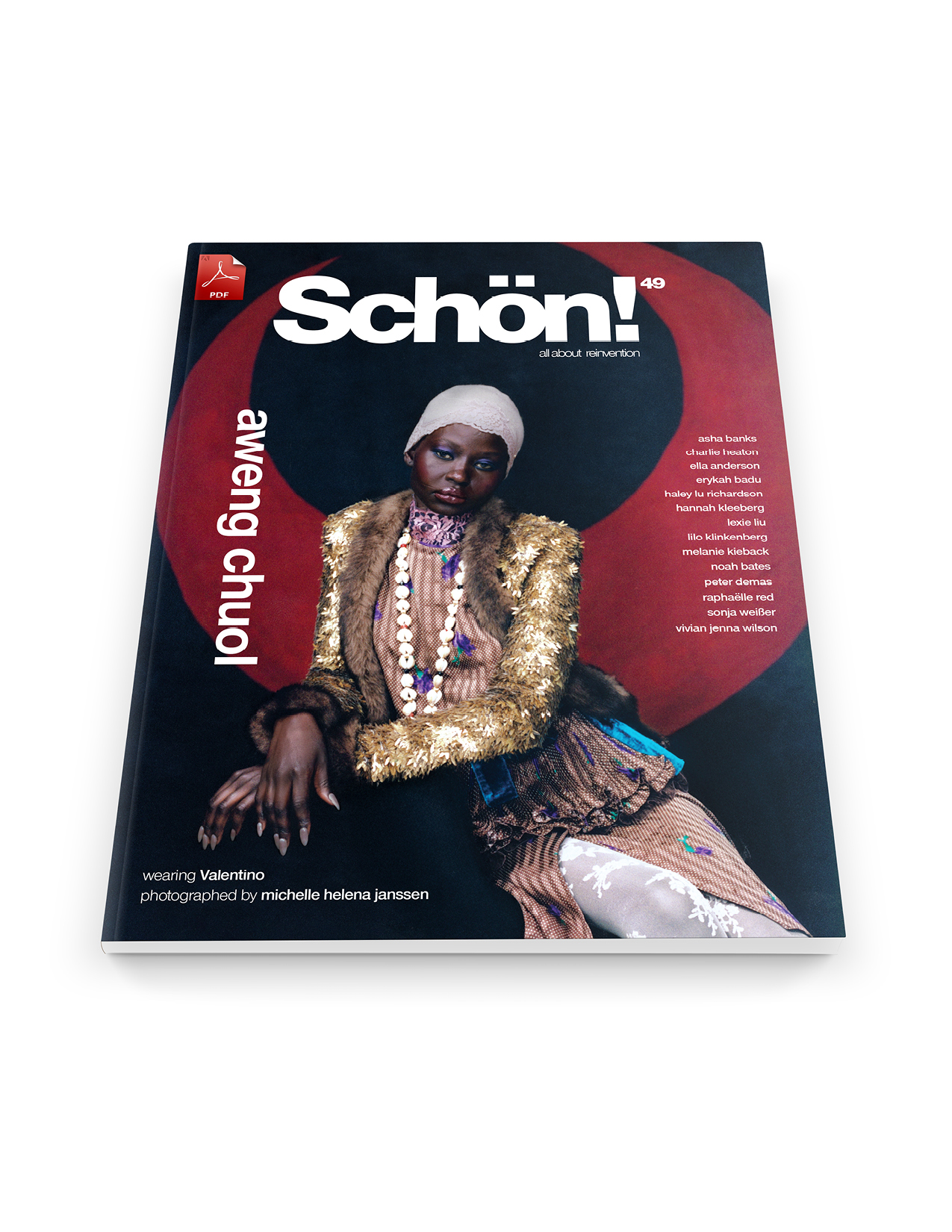

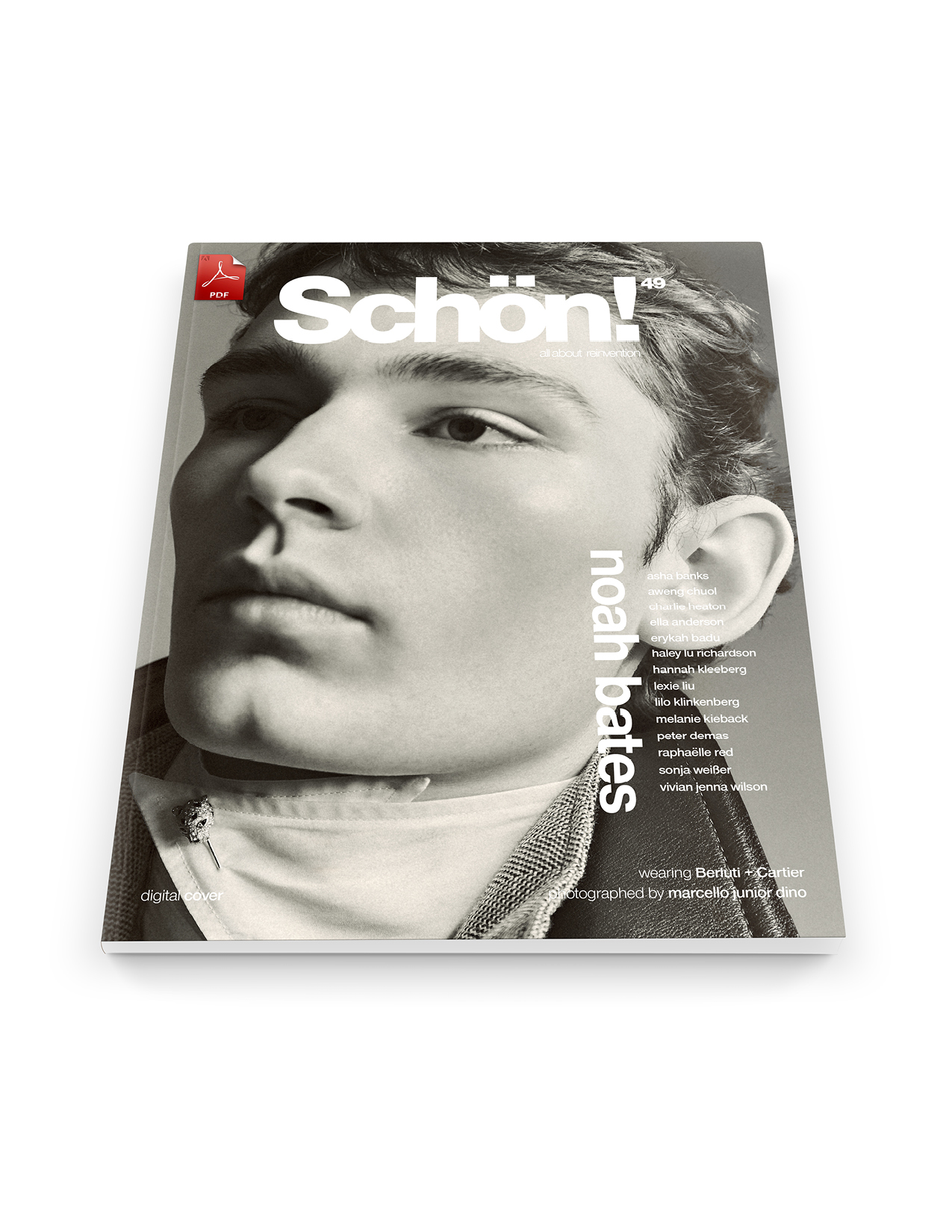

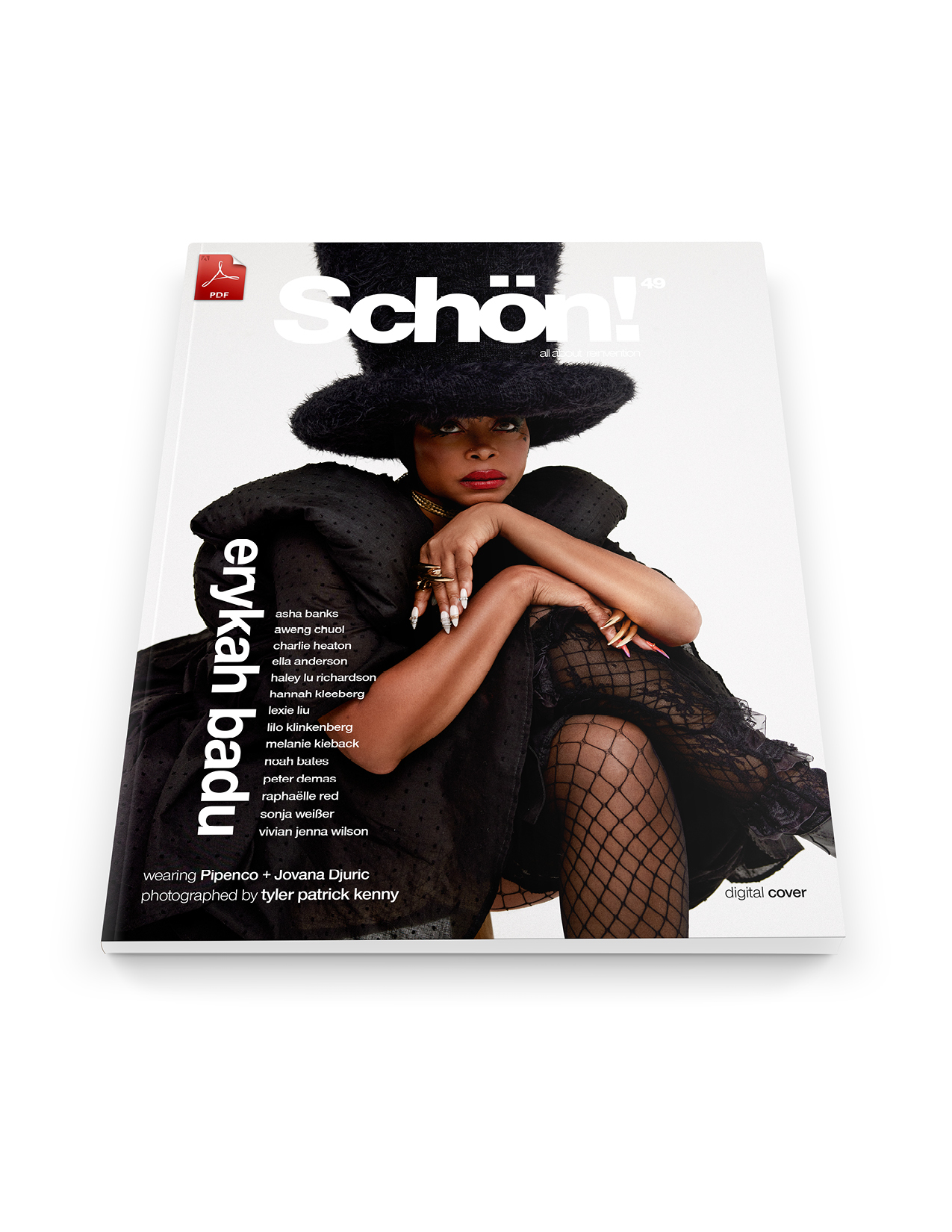

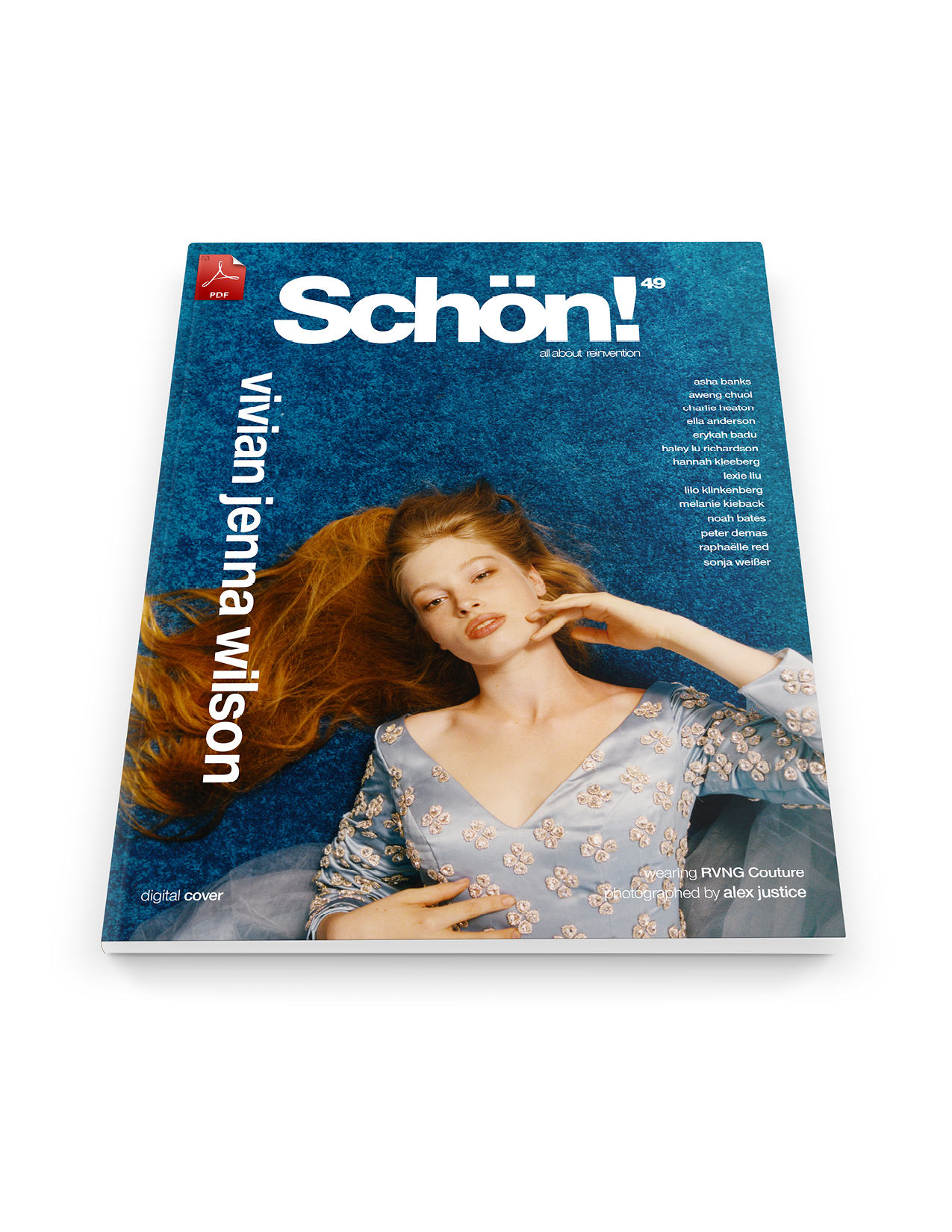

Discover the latest issue of Schön!.

Now available in print, as an ebook, online and on any mobile device.