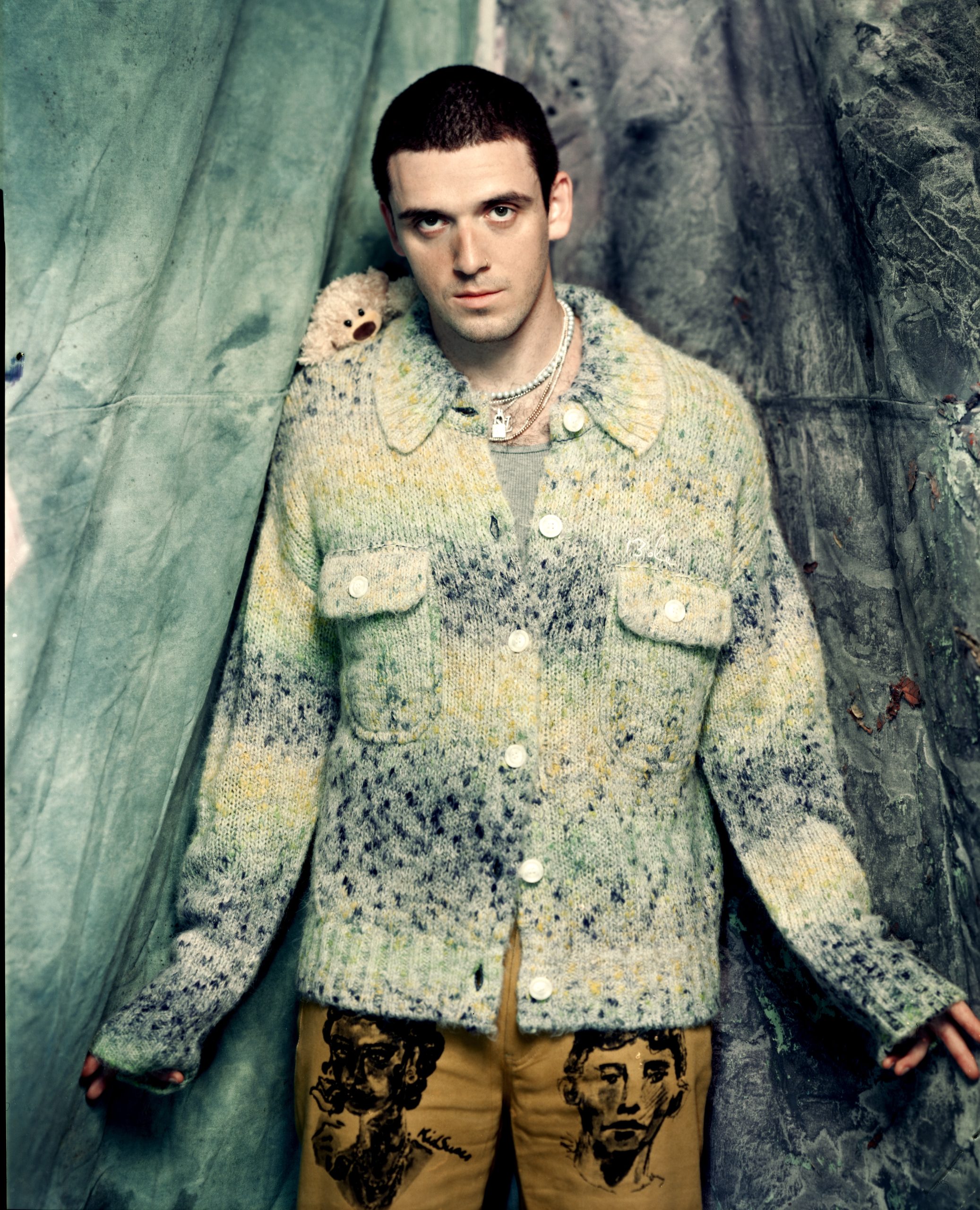

Few performers are as agile in holding multiple talents together as Nicolas Maury. Although he stepped into the international limelight with his role as Hervé in the Netflix series Call My Agent, Nicolas Maury already had a wealth of acting experiences behind him, from his debut with revered French filmmaker Patrice Chéreau, a career in French cinema, to an appearance opposite Maggie Gyllenhaal in Paris, Je t’aime. But, it was on stage that Maury really began to weave together his talents in one web, training in Paris at the national theatre school before moving onto regular roles both in theatre.

Now, in 2024, he acts, directs and writes, and, last year, he released his debut album. After his shoot with Schön!, we find Nicolas Maury in a secluded cocktail bar at The Hoxton in Paris, and he settles into a plush armchair to discuss some of the subjects that animate him most. He transmits an insatiable will to understand and share, and is generous in formulating his experience into words. Delving into the idea of generosity on stage, of discipline, he describes how various art forms all combine to create a form of self-less truth, always in the search for human encounters.

In conversation with Schön!, he discusses everything from the word “queer,” Pasolini, and Kleist, to avoiding virtuousness and intentionality. His ultimate goal, he tells Schön!, is achieving the ultimate connection.

What projects are you working on at the moment?

I’m shooting a series called Ça, C’est Paris! with Monica Bellucci and Alex Lutz. It’s the same producers and directors as Call My Agent. I’m the only original cast member in this new series. It’ll be out next autumn, I think. I’ve also been on stage recently in A Prince of Homburg by Kleist, directed by Robert Cantarella, and I’m also going to play in Phèdre by Racine in June, directed by Murielle Mayette. I’ll be playing a woman in it – Oenone – as Murielle thought that I should play a woman. Oenone has a very tragic destiny.

I’m also working on my own project, Les Saisons, with Arte. It’s the story of a woman who falls in love with two men at the same time and we follow them from their 15th to 45th birthdays between 1991 and 2021. It’s a series of four 50-minute episodes. It’s highly emotional and is a sort of portrait of France in recent years.

When looking at your career, the first thing that strikes me is the multidisciplinary nature of your work – do you feel enriched exploring various art forms, rather than seeking accomplishment in one discipline?

This idea of changing roads and paths whilst always maintaining the same heartbeat, the same state of mind – and switching not to show off a form of virtuosity, but rather to find something honest – has always been important to me. I move from one art to another, as a way of getting closer to what we call the chambre à soi – a room of one’s own – that moment when you encounter yourself, just as great writers do. By diffracting myself, I focus on who I actually am. By diffracting myself into multiple versions of myself, I don’t go looking for a sense of self in myself. My ego is not at the heart of everything – my vision is.

It’s this feeling of being as close as possible to this honesty of feeling, singing, directing and acting in both theatre and film. They are two very different worlds. Theatre is the most extreme and austere form for a performer. But, it’s my first calling. It’s an art that takes all of me when I do it. There has to be a verticality to the spoken word. There has to be a form to poetic art and, with a director, there’s always a form. I only like directors who write their own form. I don’t like television theatre, I don’t like theatre with stars who get a thrill out of doing theatre.

How did you get into acting?

I started acting professionally when I was 16 and then I went to the Conservatoire National in Paris. It was almost as if to prove something to my parents because my parents aren’t from that background at all. It was as if to say to them: ‘I got into the conservatoire – which has 2,500 people auditioning for 25 places every year.’ I had to prove it to myself too. Patrice Chéreau had prepared me for it because I had met him working on a film together.

This idea of working between these different mediums, these different languages, is central. You don’t play Marivaux the way you play Kleist, the way you play a contemporary author… It’s all quite dizzying and magnificent. For example, I’ve been working on Kleist since last January and it’s taking up my whole life. Every day, I do a read–through of my role, which is two and a half hours long. It’s like a sport. In fact, it’s a high-powered sport – you have to be fit, you have to have stamina, real discipline and rigour. But always with a sense of truth. You’re working on a written language, in German from 1811, and you have to find an impression of the moment, an immediate impression, in front of 500 people: that’s marvellous, it’s like music.

It’s almost mystical.

Absolutely, religious, mystical – religious in the godless sense. Etymologically it’s about connecting people: religare. Theatre is a religion in that sense.

It’s a very ancient art form!

I love that word, ancient.

You mentioned music – how does music fit into this?

I released an album a year ago, Les Porcelaines de Limoges, and now I’m going to make a documentary about my music with Didier Varrod, who’s in charge of music on France Inter Radio. He filmed me on the train I used to take, the Paris-Limoges line, and at a festival I did last year. It was an incredible experience, stopping everything for two years to record, to go into the field of music. This place of encounter is a form of nudity, where you’re almost more naked than on stage: suddenly, singing means completely losing yourself. You have to have very little ego. In any case, it revolutionised my journey. As I was signed for several albums, I’ve already started work on a new album.

I found a real coherence when listening to it between your theatre work, your film work, and the music you write. There’s a sense of self-narrative, an emotional truth…

I didn’t want it to be a case of: “Oh he’s trying to be a singer now.” I didn’t want it to be an event, because it’s not an event. I think this is a pretty good example – when you find a vine against the front of an old house, the vine twists and turns in multiple directions, but the root at the base is the same. These different directions are inspiring for me, they’re part of any being that grows. Anything I’ve tried to do with too much strategy or intentionality has never worked.

On the other hand, I’m someone who takes a long time to incubate, to receive. I know it’s not very fashionable at the moment, but I don’t like intentionality or virtuosity. I don’t like being given something that’s a success. Either it’s a great success, but with a touch of madness in it, or it’s duller, more muted, more indecisive. Often, what is highlighted is the success itself, and not the disaster. For me, disaster is something that makes me write. A falling star. Everything ridiculous fascinates me. I find it incredibly vivid, it can make me fall in love. It’s not charming or seductive.

Everything that is a failure, has its specific beauty.

To really show imperfection and share it with people: that’s a form of grace. I really like broken people. It’s one of the hardest things to reveal though. It’s not all about coming to terms with bad anecdotes or things that happened. And that’s who and what I’ve been studying, who I’ve been observing in literature, who I’ve been obsessed with since I was a child. As I’ve gotten older, I can say it: my path leads towards deep, hidden forests.

It’s also a form of self-acknowledgement, perhaps?

Yes, to meet oneself, to forgive oneself, to understand oneself. It’s one of the most difficult things to formulate and to give yourself this possibility; today’s society doesn’t encourage these explorations, we’re very focused on achievement. Has the binarity of failure and success worked really? These are areas that don’t interest me.

There’s a book I love – The Queer Art of Failure by Halberstam – that captures the queerness in this imperfection.

What I like about the word “queer” is that it’s so indefinable. I was on a radio programme with a presenter who is very straight – I know, it’s strange to define him as ‘very straight’. Either way, his name is Matthieu Noël, he invited me to appear on his programme because I was president of the Queer Palm at Cannes. He was trying to understand what was meant by the term, with difficulty. What I find beautiful about this term is that it’s very much alive, very difficult to discern, and that’s what queer is for me. It’s very much alive. Artistically, it inspires me.

As an artist, the beauty of being human is the beauty of continuing to meet people – even those you’ve already met. For me, this works for everything: an encounter needs to be repeated, an encounter needs to be revisited, as Duras says: “Encounter is a difficult thing. It needs to be re-examined, this act of meeting.” It would avoid a lot of wars, I think.

Sometimes meeting also means conflict. It’s not just in the sense of communion – it’s the act of thrashing things out, of saying “I don’t understand what you’re saying”, of never giving up on understanding each other. Even my friends tell me when I won’t let things pass, “It’s a slog, let it go”. But for me, it’s a way of not being superficial about things.

If I understand something, I start to know myself a bit and I love passing that on to people. Especially to young actors and new friends. This rigour of truth (a dangerous word to say, it can be dictatorial), is the fact of assuming who you are.

Does queer as a label, when applied to your work, interest you? Is it important to you?

Thinking about it doesn’t inspire me. I like escaping from conformity, I like contradiction. I like the fact that it’s an eternal quest. Today, I think the risk is that to label anything queer might become an accessory or a trend.

You have to get rid of excess when working in acting. I have my way of doing my job, I create my own projects and I’m a bit of a soldier when I’m working. I ask myself, how do others work? But ultimately my practice is my way of understanding. Cocteau said, “Too much is just enough for me.” For me, it’s a bit like that. Labels like ‘gay films’ reduce work to something restrictive. But to make a queer film is to open the floodgates. It means going into unknown areas.

Exploring doesn’t mean knowing the destination. I think it’s ancient. We’re in a post-post-post-post art form, which means I’m anything but amnesiac. I haven’t forgotten what Greek tragedy is, or what early opera is; we’re in the post-era of that. It’s as if we have to go through the ruins of all these forms, to arrive at something new. People say, “It’s too intellectual”; but on the contrary, I think it’s very sensual.

That’s the way I like to think about the idea of queerness. Pasolini and Fassbinder for example, represent this. I don’t know if they’d be defined as queer. However, Fassbinder – I’ll never get tired of his work – worked in theatre, put on 3 plays a year, 4 films a year and produced television films that were grandiose… He carved out his own territory. I don’t know if it’s queer, but it is for me. To look at things as he did is to be queer.

I’ve always thought Pasolini’s approach to making art is extremely queer.

His love of the ancient is exceptional – you mentioned this word earlier, it’s a word I love – anything ancient is incredibly punk these days. Like when he filmed Maria Callas, when he filmed his mother in Mary Magdalene, or when he captured the faces of working-class Italians in The Gospel According to St. Matthew, when he filmed Christ as a handsome man,… these are all examples of queering cinema. He always spoke about the aristocracy of the people. It’s the love of two things that don’t go together. That’s my queer heritage: saying two terms – like chiaroscuro – but the two are not opposites as you might think. It’s two terms that come together, like the feeling of ‘truth’. That’s what interests me.

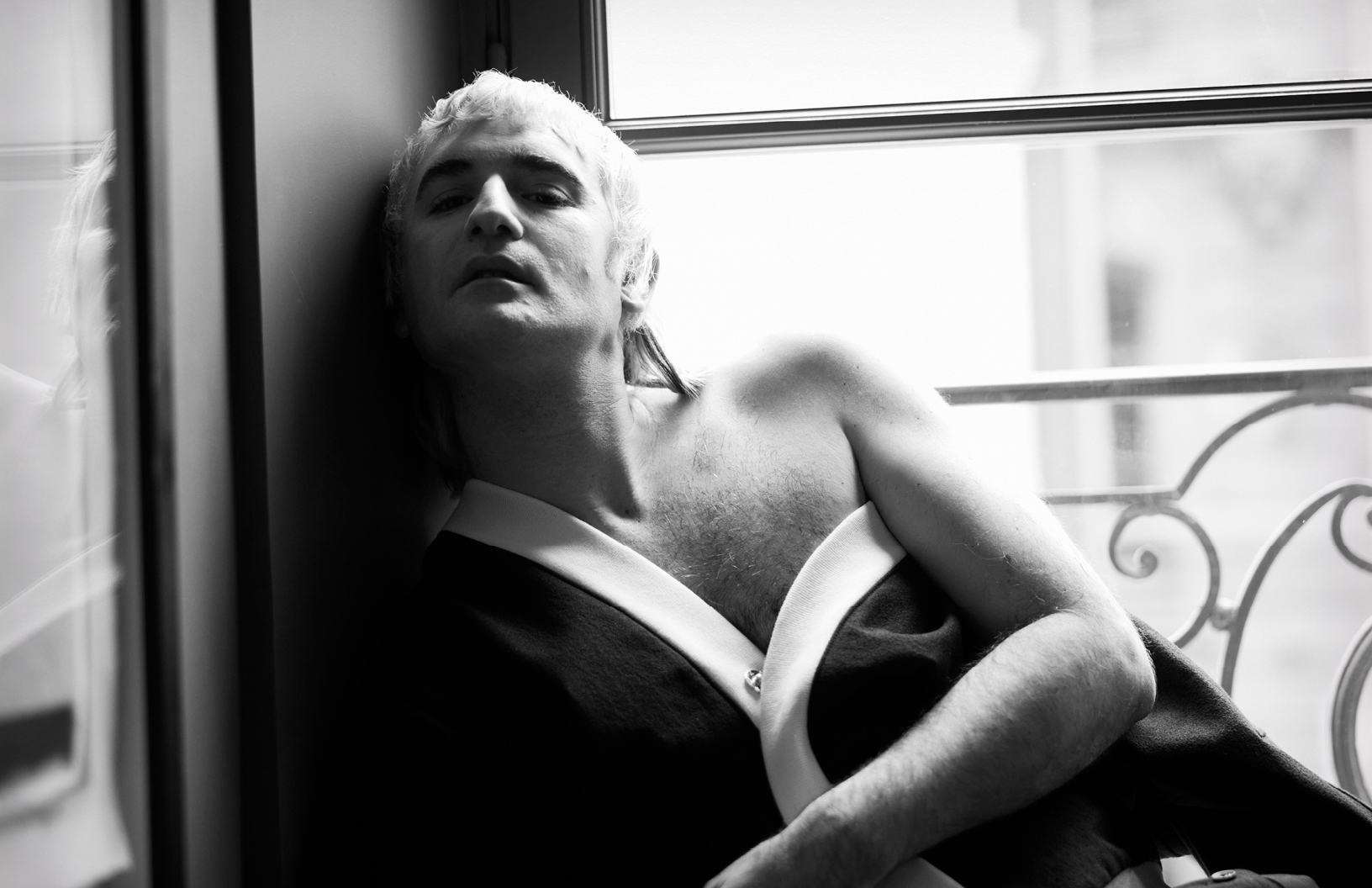

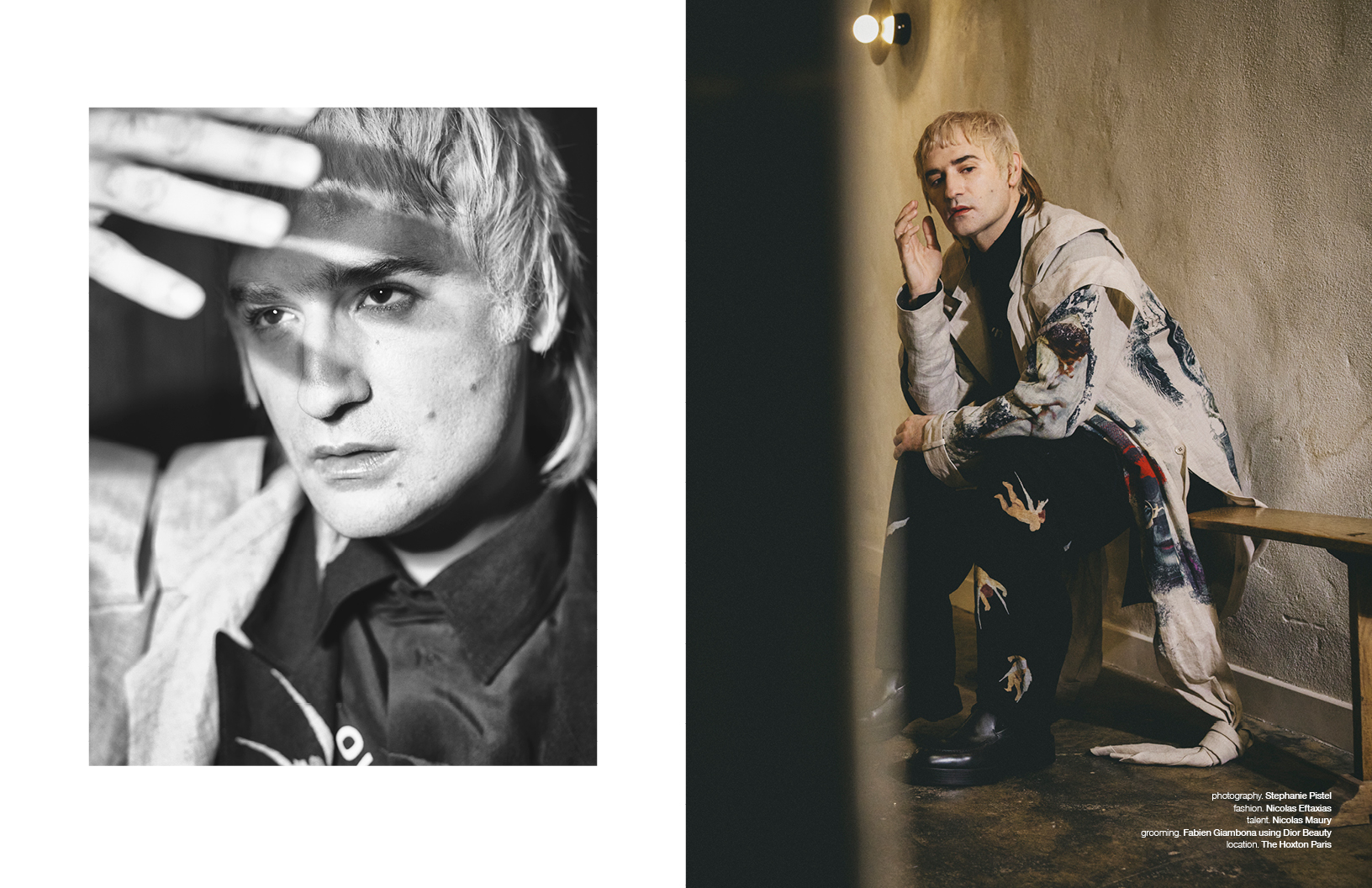

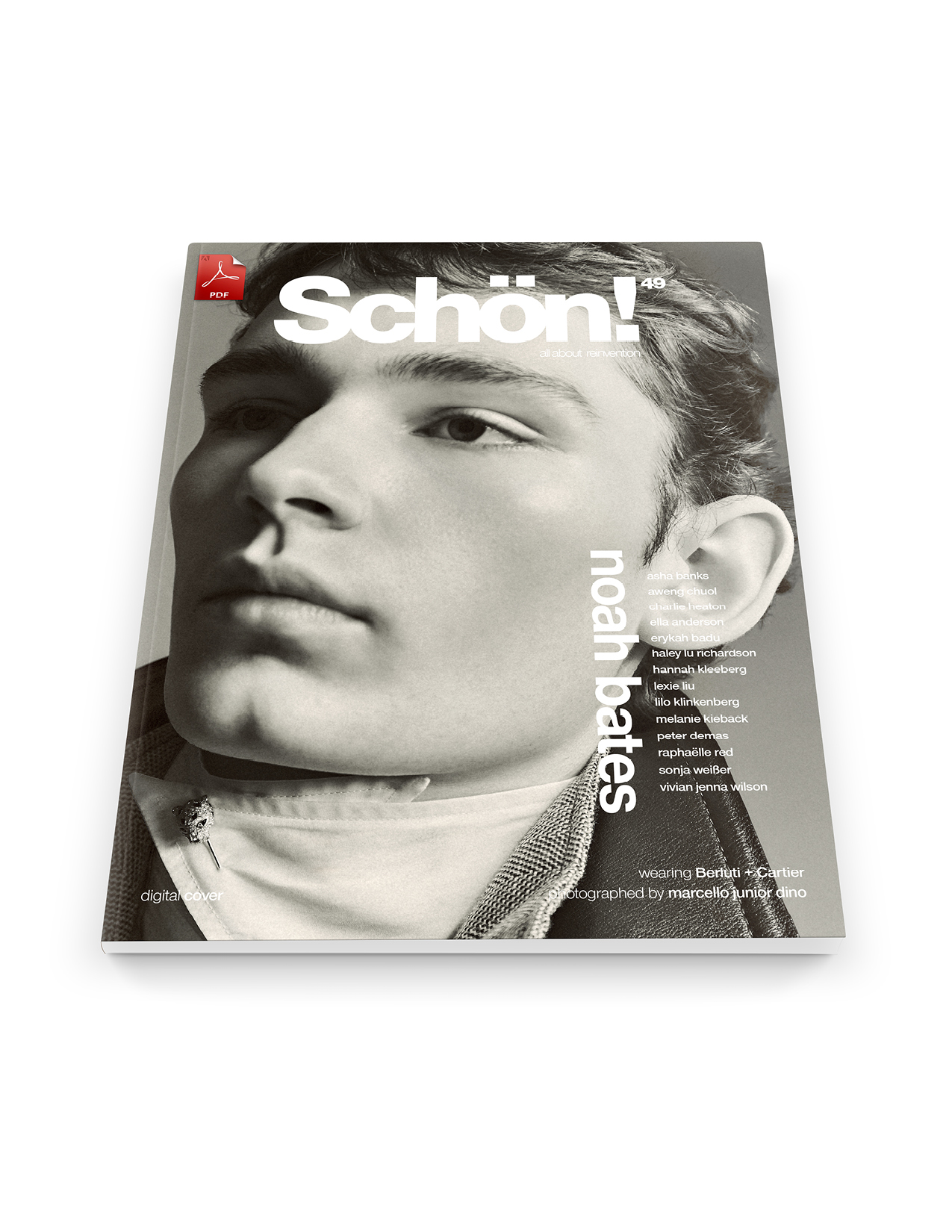

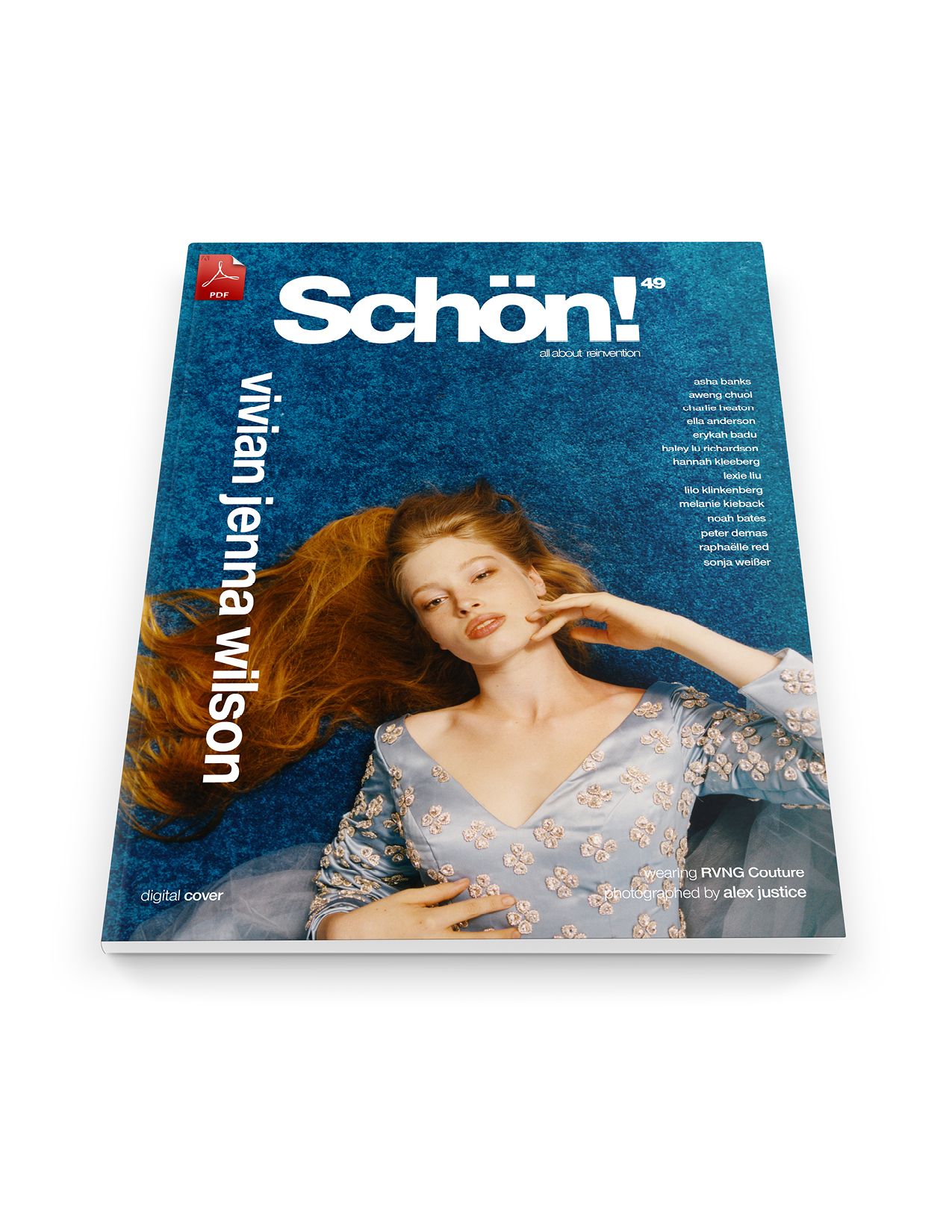

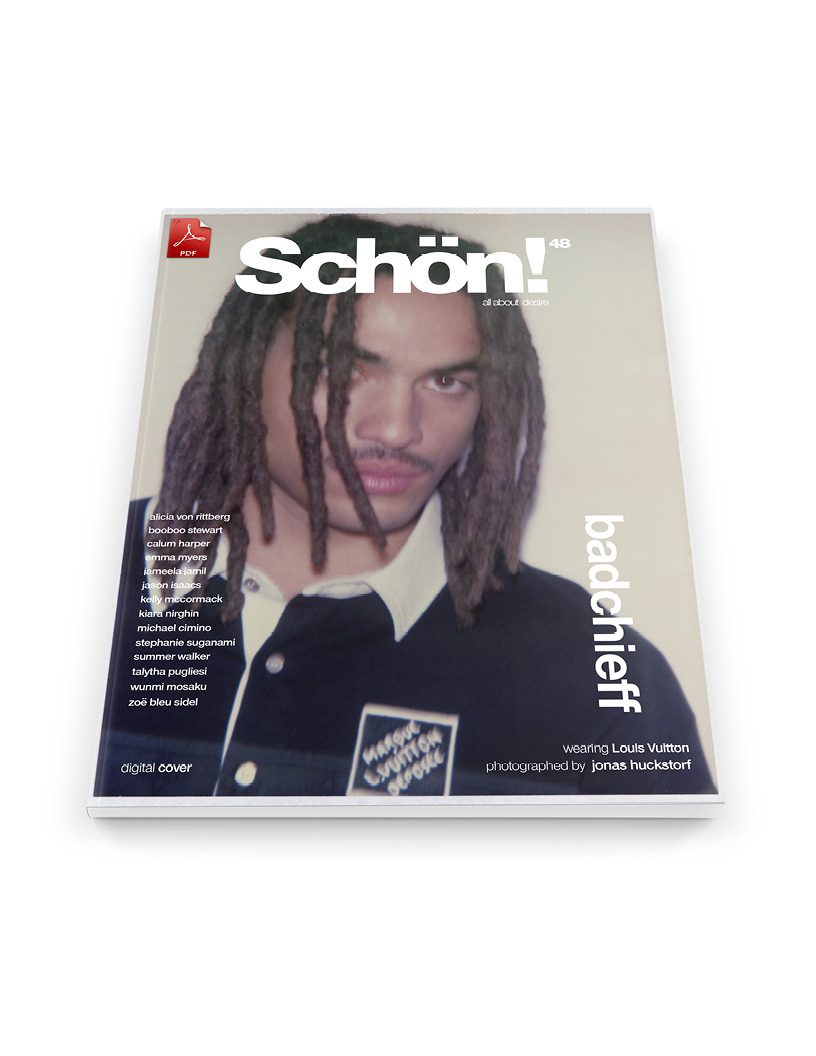

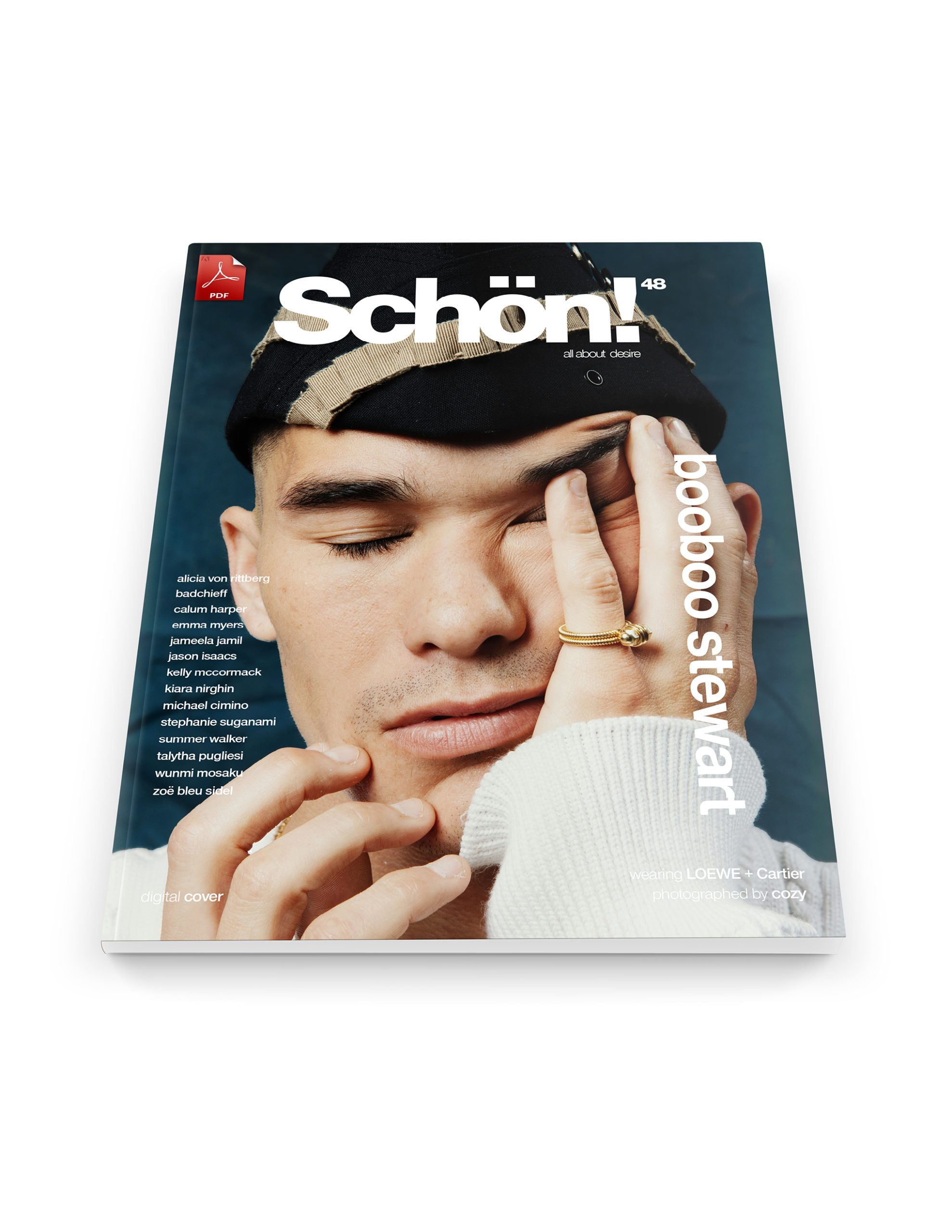

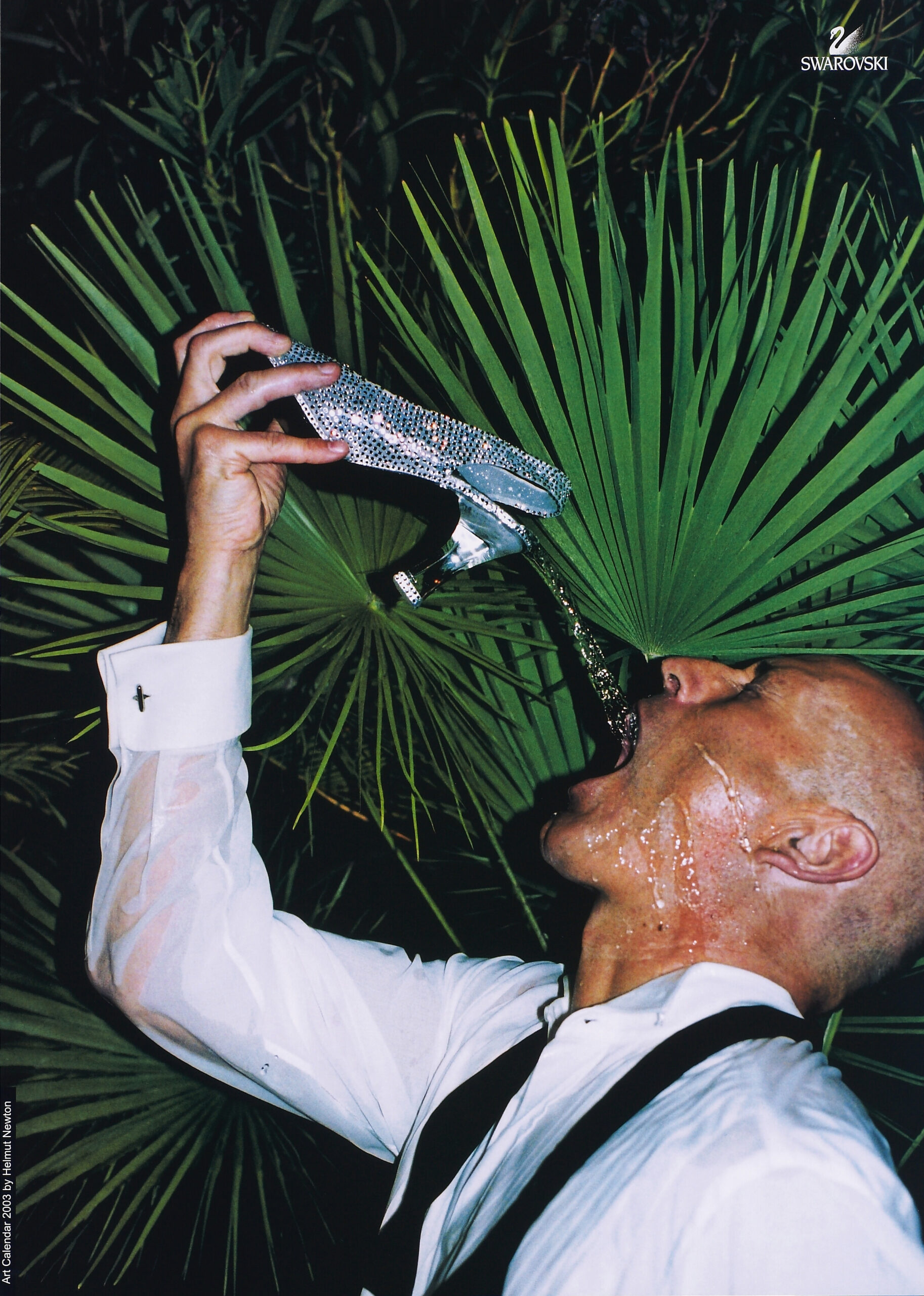

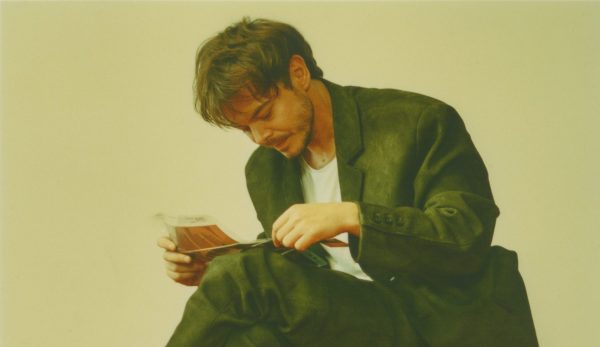

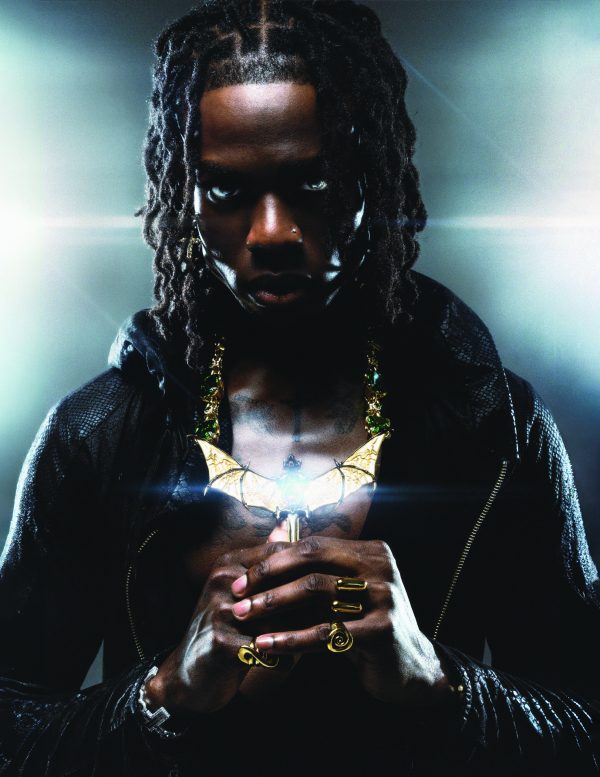

photography. Stephanie Pistel

fashion. Nicolas Eftaxias

talent. Nicolas Maury

grooming. Fabien Giambona using Dior Beauty

location. The Hoxton Paris

interview. Patrick Clark