Opera Gallery New York is set to open Lines in Motion, a group exhibition running from May 8 – 31, 2025, that dives deep into one of art’s most fundamental — yet endlessly expressive — elements: the line. Spanning works created between 1948 and today, the show gathers a heavyweight lineup of artists including Pierre Soulages, Sol Lewitt, Hans Hartung, Georges Mathieu, André Lanskoy, Serge Poliakoff, Victor Vasarely, Richard Prince, Carlos Cruz-Diez, Pablo Atchugarry, John Helton, Pieter Obels, and Fred Eerdekens.

Grouped into four themes — Lyrical Abstraction, Op Art, Art and Text, and Sculpture — the exhibition traces how artists have used the line as both form and feeling. In the lyrical works of Hartung and Lanskoy, the line becomes a raw, emotional gesture: multicoloured pastel marks in P1948-16, or the tumbling abstraction of La Bataille d’Uccello, which reimagines Renaissance battle scenes through fluid, spontaneous strokes.

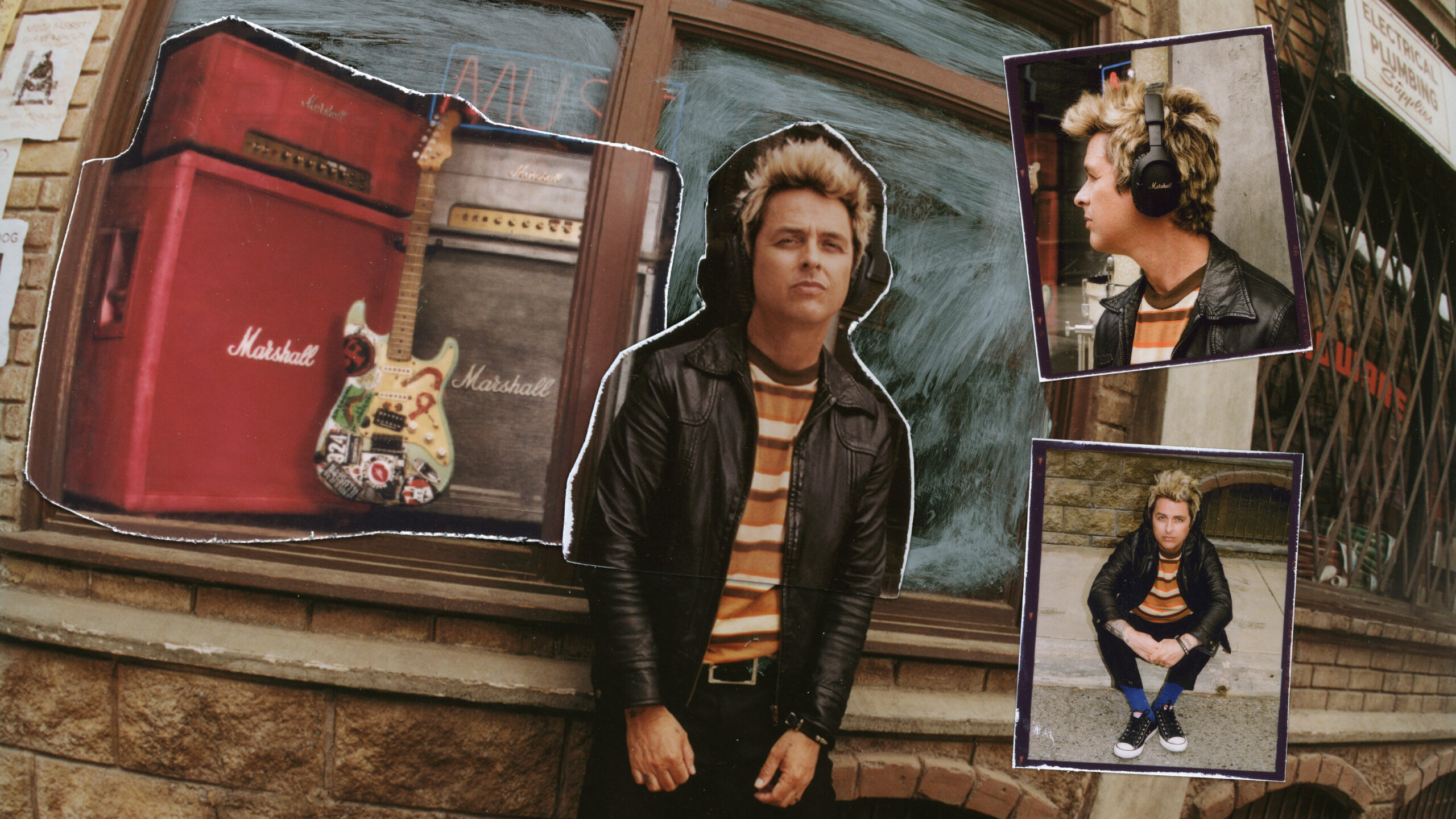

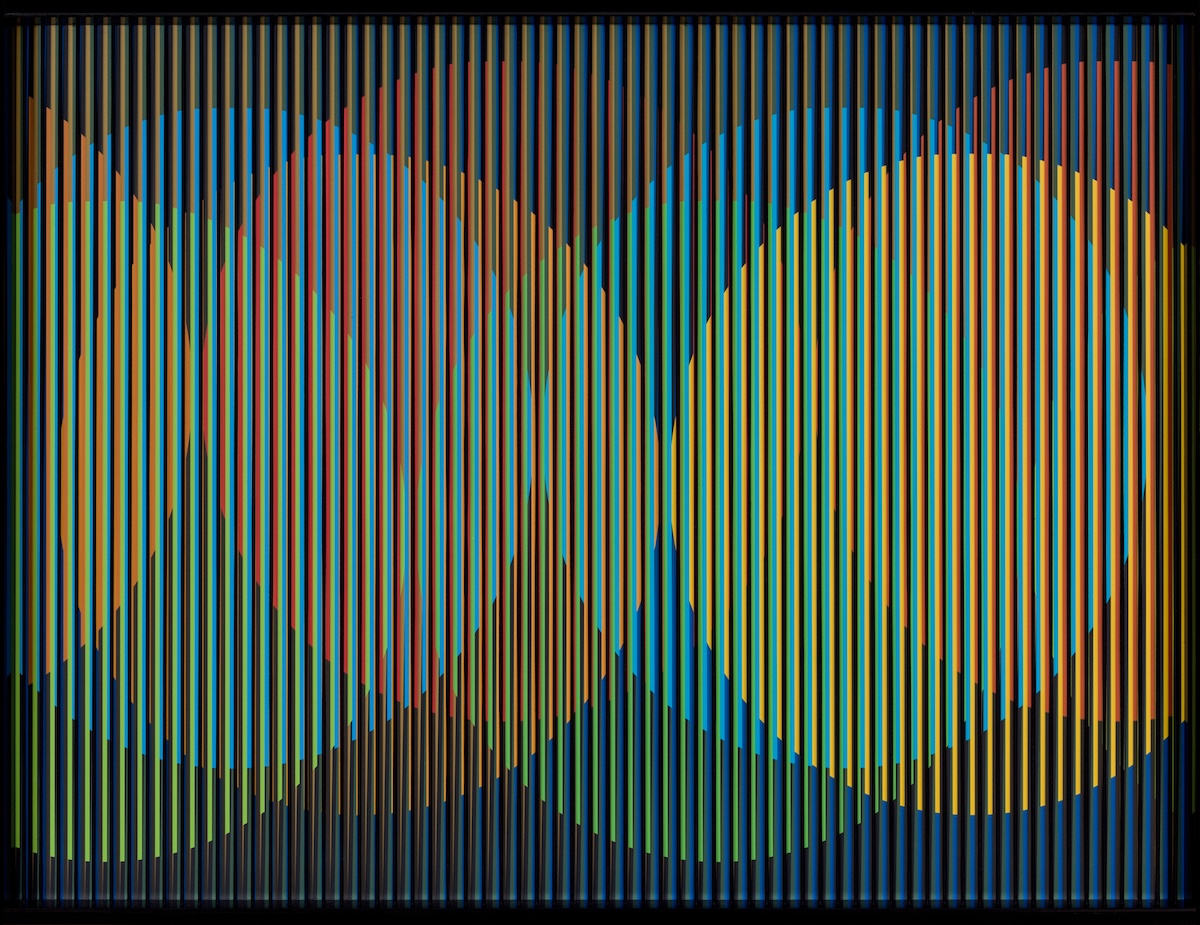

Op Art’s cool precision appears in Victor Vasarely’s Anadyr-R, where converging lines and geometric patterns create illusionary depth, and Carlos Cruz-Diez’s Cromointerferencia Espacial 13, where colour-charged lines seem to vibrate and shift, even when still. Both artists channel kinetic energy and technological fascination, echoing a mid-century optimism — and unease — about the future.

That tension between control and chaos runs through the exhibition. As Art Curator Christian Rattemeyer writes in the catalogue essay, “In the beginning there was the line. At the risk of sounding like a cliché, there is little opposition to the idea that the line is a fundamental building block of all visual expression.” Rattemeyer reminds us that many works in this show — especially those by Mathieu and Hartung — emerged from a postwar era defined by the existential threat of the atomic bomb, where mark-making became an urgent act of sense-making. As the exhibition moves into more contemporary terrain, the relationship between freedom and line softens, opening up to play, ambiguity, and experimentation.

That playful spirit comes through vividly in the intersection of Art and Text. Richard Prince’s Untitled (2008) uses language to cheekily deconstruct American culture, while Fred Eerdekens sculpts delicate metal strips that, when lit, project shadowed words and phrases onto the wall — transforming abstract forms into fleeting, poetic meaning.

In sculpture, the line becomes physical. Pablo Atchugarry’s marble carvings suggest elegant folds of drapery, while John Helton and Pieter Obels take heavy bronze and corten steel and bend them into shapes that seem impossibly weightless.

Whether sweeping and emotional, coolly precise, or texturally physical, the line remains one of art’s most potent tools — a way for artists to navigate history, technology, memory, and meaning. With this show, Opera Gallery reminds us just how much can emerge from something as simple as a line, drawn across space.

Carlos Cruz-Diez, Cromointerferencia Espacial 13, 2015, chromography on aluminium, 23.6 x 31.5 in | 60 x 80 cm

Discover more about the exhibition here.

photography. Opera Gallery, On White Wall

words. Gennaro Costanzo