In the growing shadow of the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements, conversations about abuse and sexual malfeasance have slowly entered the mainstream. Across western media, voices have been raised calling against mistreatment and discrimination, often to considerable albeit long-overdue consequence. However, the conversation in the West thus far has had a limited scope, frequently lacking a global perspective.

Enter Refuse Club, a new brand coming out of New York with roots in China. Designers Yuner Shao and “Stef” Puzhen Zho helm the project, the current aim of which is to bring further attention to issues surrounding sexual harassment, contemporary culture and, ultimately, one’s freedom to express themselves.

Although the project began in New York, Shao and Zho both hail from Chongqing, China, a location where they eventually hope to bring their work. By incorporating the many stories brought forth both in and outside China during the height of #MeToo, the duo has created a line of clothes rooted in traditional Chinese culture deeply influenced by the modern digital age. We spoke to the Refuse Club team about their name, expanding to China, and what the future has in store for the brand.

How did you two meet, and when did you discover your shared artistic interests?

We were friends when we both studied at Parsons. By that time, we always shared opinions of recent news and trends, and we thought it was interesting to blend fashion with some of those topics.

The Refuse Club name comes from the Salon des Refusés, a mid-19th century Paris exhibition that featured paintings too “scandalous” for the Paris Salon. In what ways does that story inspire your work?

Stef: I spent half of a semester writing a paper about Édouard Manet in a writing class first year at Parsons. That’s how I learned about the 19th century French Salon des Refusés, “the exhibition of rejects.” I always loved the name and the whole agenda behind it – to be independent and spontaneous, to show the world what you have to offer as an artist… It was so wild to me. And I think Yuner liked the idea of forming a community, so it worked out.

Yuner: Salon des Refusés introduced a new style of painting, giving the independent artist a chance to showcase… We also chose to showcase our collection outside of the traditional fashion week calendar and did not choose the schedule and venue of the traditional New York Fashion Week. As a new brand, our voice is easily overwhelmed by other big names on the white T-stage of fashion week.

For all of the traditional elements you incorporate into your collection, there are also plenty of distinctly modern components; pieces feature phrases like “404 NOT FOUND” and patterns emulating digital glitches, for example. How does this blend of traditional and modern play into the overall ideas and themes of the collection?

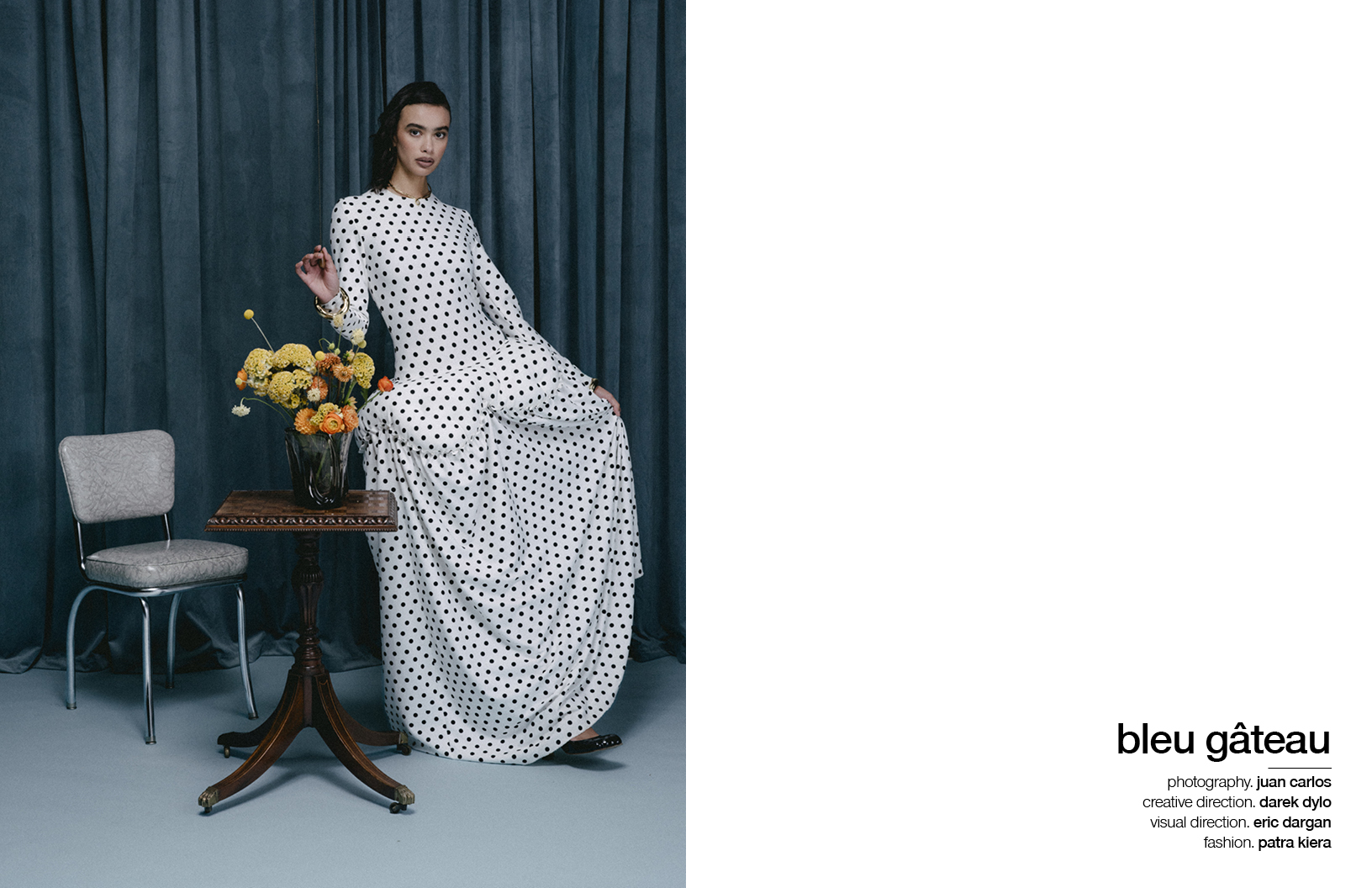

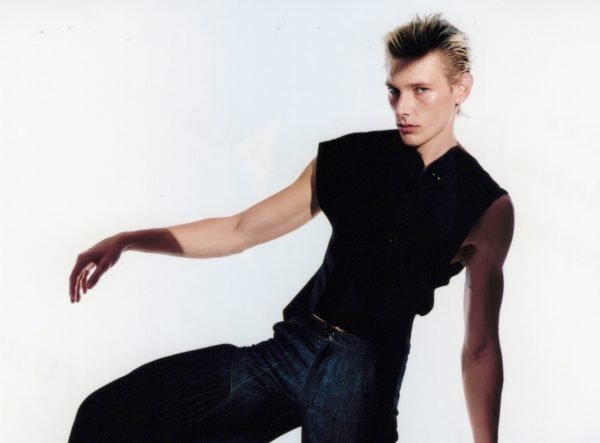

Y: Since both of us are interested in textiles, we started doing illustrations that turned into a booklet called “21st-century safety guide for women.” Each artwork is an irony which referred to some social event. I chose the traditional Chinese Qipao dress as the main shape for this debut collection. It is such a classic and elegant dress that can represent Chinese woman. The Qipao dress is known for its super slim fit – few people know that it was originally straight and loose. In order to approach western taste, people changed it to a slim fit that is not practical anymore. We deconstruct the Qipao this time because we want to bring back its practicality as well as breakthrough Chinese women’s stereotypes in western society. And then we screen printed our artwork on the traditional brocade fabric. Most traditional floral silk brocade was only used for women in the past in China. This time we also did menswear using this traditional Qipao dress silk to emphasis the genderless.

S: Somehow we both ended up having a focus on screen printing. We are both kind of old school for still believing in the power of image while knowing every day we are floating in the endless sea of imagery. Some photographers change the world with one photo; we would like to do the same with fashion. Qipao was one of the image archetypes we wanted to break down. We made the Qipao a loosely fitted dress to take away its underlying eroticism.

To answer the second half of the question, we read an intense amount of cases just so we don’t have to talk about individual incidents. A single case could be exceptional and deceitful, but when you come across a number of victims getting attacked wearing basic clothing like a quilted puffer, a pair of rain boots, or running shorts, you doubt if there’s any universal connection between the victim and “how sexy they dress.” Every woman in those unfortunate cases, her story belongs to her and her family exclusively. We don’t have the right to tell their story, but the “bigger story,” the story of so many women, happening in the past, now, and future, is our story – a story we are entitled to tell.

Right now your work is only available in the US, but you plan on expanding to China soon. How do you think your collection, which features themes of the #MeToo movement, will be received in China in comparison to your reception in the US? Are you nervous? Excited? Both?

Y: We are excited but also nervous, because Chinese customers might not be used to adding political statements into the collection. We are expecting that our collection will act as a [medium] to raise conversation. At the same time, some messages are hidden in the prints or in the inside flap of the pockets. There are some people who are not interested in showing political statements who still can enjoy our clothes.

S: As for the customers’ response, we thought about possible reactions and decided that we will keep the concept discreet. We have no intention to offend anyone by making assumptions. Instead, we merely want to encourage diverse conversation and engagement. We hide the hints in the lining or behind a print. There are different levels of accessibility, we believe. Most customers might just like our design for its colour or style. They probably won’t bother finding out the meaning. The ones that pay attention to details and spend time reading about our concept underneath must have a gentle heart. People like that judge carefully.

What similarities have you seen between conversations about the #MeToo movement in the US, where the discussion made headlines, and China, where the hashtag was banned across social media?

S: #MeToo has made a big hit on foreign social media, making it seem that sexual harassment is a first world issue. For those in developing societies, issues relating to sexual harassment are very easy to ignore. But then again, at least the Western countries engage in #MeToo and help improve some of our moral awareness. It is better than nothing. We noticed that in addition to China and other East Asian countries, including developed country like Japan and South Korea, although the #MeToo hashtag has not been banned, the discussion is still short. We still find victim-blaming happening a lot.

Do you see this theme carrying on into future collections?

We might focus on different issues through seasons, but I think feminism is a big topic. There are so many aspects that we can still talk about in the future.

What are some goals you have for the future of Refuse Club?

Our current goal is to encourage diverse social, political conversations because in China, not enough people in the art and fashion industries with access to exposure talk about things that are relevant. Our next direction might talk about unemployed small-town youth in Chinese suburbs. They have their own countercultural fashion scene going on, which is very cool.

Discover more about Refuse Club here and make sure to follow the brand on Instagram.

all clothing. Refuse Club AW19

photography. Xiaodan Lian (first half) + Xin Wang (second half)

fashion. Yuner Shao + Stef Puzhen Zhou

models. Charlie Ward + Nastya Siten (first half); Ali, Huihtui Ma + Hanwei (second half)

hair + make up. Agnes Shen + Team

words. Braden Bjella