“My ultimate dream would be to make a queer Disney princess movie.”

Those were not the first words I expected to hear coming out of Jamie Margolin’s mouth. I’ve known about Jamie for a few years because an article she wrote when she was fifteen, “Racism is the Root Cause of the Climate Crisis”, was my introduction to the interconnectedness between colonialism, imperialism, extraction and white supremacy. Her book, Youth To Power, which just came out last year when she was eighteen — she’s nineteen now — is a must read for anyone over the age of thirteen who cares about this world and wants to do something about it.

Jamie is one of the founders of Zero Hour, a youth-led climate action collective that organises marches, strikes, lobby days and educational campaigns for climate justice. She is currently suing the state of Washington for continuing to worsen the climate crisis, and she was also a surrogate and delegate for Bernie Sanders.

On the day we met, she was in her dorm, seven days into a mandatory quarantine for new NYU students, about to start her first year in film school. I was surprised when instead of telling me she was there to make documentaries, Jamie came out with a whole new side of herself that not many people know about.

JAMIE: I want to make TV shows like She-Ra and the Princesses of Power and other very empowering queer shows, and movies like Birds of Prey to get people amped. My dream would be to make something as iconic as Frozen, but with gay characters, not queer-coded. I want us to finally be a part of the fairy tale and to have our own ‘happily ever after’ instead of being sidekicks, or a lesbian couple who got what was coming to them, or connected to something traumatic. I want a movie about a lesbian superhero instead of a 50,000th Batman movie. I’m like, ‘Okay, great, thank you, we don’t need this.’

BOJANA: In your book, you mention art as an agent for cultural shift, and culture as an agent for shift in government. It interests me that fiction is your passion because knowing your work, I thought you would pursue documentary making. It’s a great dichotomy. What drew you to those fantasy stories and Disney in particular? Because let’s face it — Hollywood and Disney are the two places art goes to be commodified.

J: I’m not interested in Disney because I love everything they stand for. I am interested in it because it’s the hallmark of family friendliness and it’s beloved to so many people. So if I ‘infiltrate it with the gay’, then so many people are going to feel included, and I am going to help so many kids feel accepted and believe that they too can get a ‘happily ever after’. I need a break from the real world where the bad guys seem to be winning all the time. Also, I was writing fiction before I was an organiser. There are videos of me from when I was three years old telling stories, holding a picture book and pretending I was reciting it. Film school is less of me departing from climate activism and more of me returning to the spark that was there before I realised the world was fucked up. I don’t want to be defined by this horrible issue that has consumed my life. My passion isn’t in screaming about the climate. I want to be known as Jamie the director and show-runner and writer who also happens to care about climate change.

I have a similar feeling when I think about Colombia and my grandmother. I want to think about her food and her self-sustaining farm. But then Colombia has the highest rates of environmental murder. So I am confronted with that darkness, while all I want to do is eat my grandma’s food and drink her coffee.

My grandma inspired me to be an activist. She was what we call a campesina — she grew up on a family-oriented tropical farm in Cundinamarca. They lived off the land — there were mango trees, chickens, coffee. It was very fertile land; anything that they planted grew. They didn’t use pesticides. My grandma had that ancestral wisdom. Whenever I’m sick, she’ll brew together something like ‘oh you put the garlic in this and the lemon on that.’ She taught me that if you treat the Earth well, it treats you well back.

B: That’s what my family does in Serbia, too. Garlic, of course, cures everything. But my family there have one cow and a few sheep. They eat from their field, which is ripe with tomatoes, eggplant, zucchini, raspberries, strawberries. They pickle stuff for winter. When I was growing up in Yugoslavia, the food was seasonal. It paralysed me when we moved to Australia and I saw countless options for each food in the supermarket. Like, you guys eat strawberries in winter, that’s—

J: Sorry to interrupt you, but I just Googled you and I saw you’re in Birds of Prey. Oh my god. I love that movie. You don’t understand. It’s my favourite film. So you know Margot Robbie?

B: What are you doing? We’re talking about sustainability and you’re Googling me?

J: You were also in I, Tonya?

B: Yes.

J: Oh my god. Okay, let’s finish the interview, and then I would like to speak to you about Margot Robbie. I am a massive fan and I know she’s not an activist but—

B: Can we get back to you being a badass who inspired a revolution?

J: Yes.

B: So… I actually came to know of you through your article “Racism is the Root Cause of the Climate Crisis”. How did you first learn about the interconnectedness between imperialism, colonialism, extraction and white supremacy?

J: I actually learned it from another Colombian activist, Juan Rueda, while doing community organising in Seattle. He helped make me aware of my own privileges and how that affects people of different cultural backgrounds who we were working with.

B How did you feel when you found out?

J: It was a gradual process, so it wasn’t like an ‘aha’ moment. Racism doesn’t exist separate from patriarchy. It wasn’t like the people enforcing racism were totally cool with women’s rights. They were also incredibly sexist, and still are. So all of these things intersect.

B: For me, there was nothing gradual about it! I read your article and it blew my mind. I just never put the pieces together that the groundwork for the climate crisis began way before the extraction of oil because I associate it so much with fossil fuel extraction. But it’s not just fossil fuels — it’s extraction in general. Indigenous lands were cleared, slaves were brought to work those lands, new plants, new species, new diseases were integrated. Now it’s so obvious. Zero Hour, which you founded, is run by people of colour. Your protests preceded, and actually inspired, the global climate strike. You inspired Greta Thunberg, and you were a kind of the modern genesis of this global uprising, and got pretty much no recognition for it.

J: Greta wrote about that in the forward to my book.

B: I’m talking more about the media for whom the international icon for that global movement became a white blonde girl instead of a bunch of rabble-rousing women of colour.

J: Technically, I’m white. I’m Ashkenazi Jewish. I’m Latina. I’m one of the whitest people in my organisation. Maybe just not white enough for the mass media. Greta didn’t ask for any of what happened. She just kinda sat outside with a sign, and the media was like ‘snap snap — perfect!’ The movement precedes us, anyway. Its genesis is with indigenous land and water protectors, who I learned a lot from.

We need community involvement, community initiatives, local legislation, stuff like that to shift the culture so that we can have a mass overhaul when the time comes. I worked very hard to make sure Trump did not get reelected, but I’m not happy with Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. I was a surrogate for the Bernie Sanders campaign and a delegate for him so it’s very clear where my politics lie.

Systemic change doesn’t mean the White House does something. It means a general community and society shift of our thinking and the way we work. It can’t just be you not using a straw. I mean, good for you, but in the end the change comes from a shift of people working together on different things.

B: Where do you think a practical solution lies when it comes to subsidised industrial agriculture? Billions of dollars are being given to corporations, who hide behind the historical image of ‘hard working farmers’ but who are actually pillaging land for the containment of millions of animals — who they then slaughter — in order for a McDonald’s burger to cost $3 instead of $20. That’s big government and big business making it almost impossible for small farmers, particularly plant-based farmers, to keep their heads above water.

J: I don’t think individual community initiatives are gonna save us all, but they do make improvements on a local level and give us a blueprint of what life could be like in cities. So while something shifts, and a small win happens in one place, it can activate others to seek it in their region.

I have a weird relationship toward the climate crisis and food – it’s taken so much away from me in terms of my future, in terms of my life, in terms of all the work that I do. Like, ‘fuck you, climate change, I’m not giving you my empanadas.’

I actually eat meat. I know it’s not logical. But the main reason I’m not vegan is my own mental health. I almost had anorexia, and I have OCD, so restricting things for me would just make it worse. I’m supportive of all that, and I want to be vegan one day, but it’s just not what works for my lifestyle right now. I totally admire all people who are, but I get people messaging me like, ‘Greta’s vegan. Why aren’t you vegan?’ I think she can make her own decisions and that is what works for her, but I have my own health and history and culture that is different.

A lot of people get turned off on environmentalism because there’s a lot of shaming to it. I’m not talking about vegans here, I mean environmentalists. I don’t believe in shaming the individual for a systemic issue.

B: Absolutely. A person wouldn’t be using plastic bags if the council banned them. But then the council sells out to petro-chem companies, plastic bags stay. There’s an amazing biochemist in Serbia, Dr. Dragana Djordjevic, who talks about how our government blames people for burning plastics in their woodfire ovens while they don’t provide them with new heating structures. She has openly told the government, ‘if you banned the sale of plastics and you subsidised people’s climate control, they wouldn’t have to heat their house with wood ovens and furnaces and they wouldn’t be burning plastics.’ She, like you, and like me, believes that our representatives are responsible for a just transition.

J: There’s a great article by a mentor of mine named Marg Hagler called ‘I’m An Environmentalist and I Couldn’t Care Less If You Recycle’. Like, I grew up getting all my clothes from Marshalls and discount stores. I don’t know if that’s eco-friendly. I don’t know if this is a Latino thing, but a lot of other Latino can relate. We could never afford designer clothes, so I never thought about fashion and wanting to look good until recently. I want to try thrifting now because my mom never believed in secondhand. Her mom was super poor but insisted that the few pieces of clothing that they did own were new and never secondhand.

B: My mom was like that, too. She’d get very upset because I was into grunge, and she cried when I wore ripped leggings, begging me not to wear clothes that made me look poor. I was like ‘Mom, that’s the look!’ I got some nice stuff so she would feel better. I never really buy new clothes anymore. Fashion is overwhelmingly wasteful, and I know I am saying this in a fashion magazine, but there’s no one reading this who doesn’t know it. The fashion industry has enough fabric to clothe the world thirty times over.

J: The only type of fashion thing that I will invest in is makeup. I feel like that is very important. I’ve done two red two real red carpets in my life. One was the MTV VMAs. I learned that the Dakota Keystone Pipeline had leaked, and I was like “Well, I need to put together a look. What do I have?” I had some eyeliner, and I asked a makeup person to do it on my face like tears of oil, and then I asked someone to write on my arms. All these other people were in their designer looks, but because I made a statement with eyeliner that you can get at a drugstore, I was in all the blogs.

Support Zero Hour on its website. Jamie Margolin’s book, Youth to Power: Your Voice and How to Use It, is available now.

photography + words. Bojana Novakovic

fashion. Nicolas Eftexias

talent. Jamie Margolin

hair + make up. Brenda Johannesen

retouch. Studio Navona

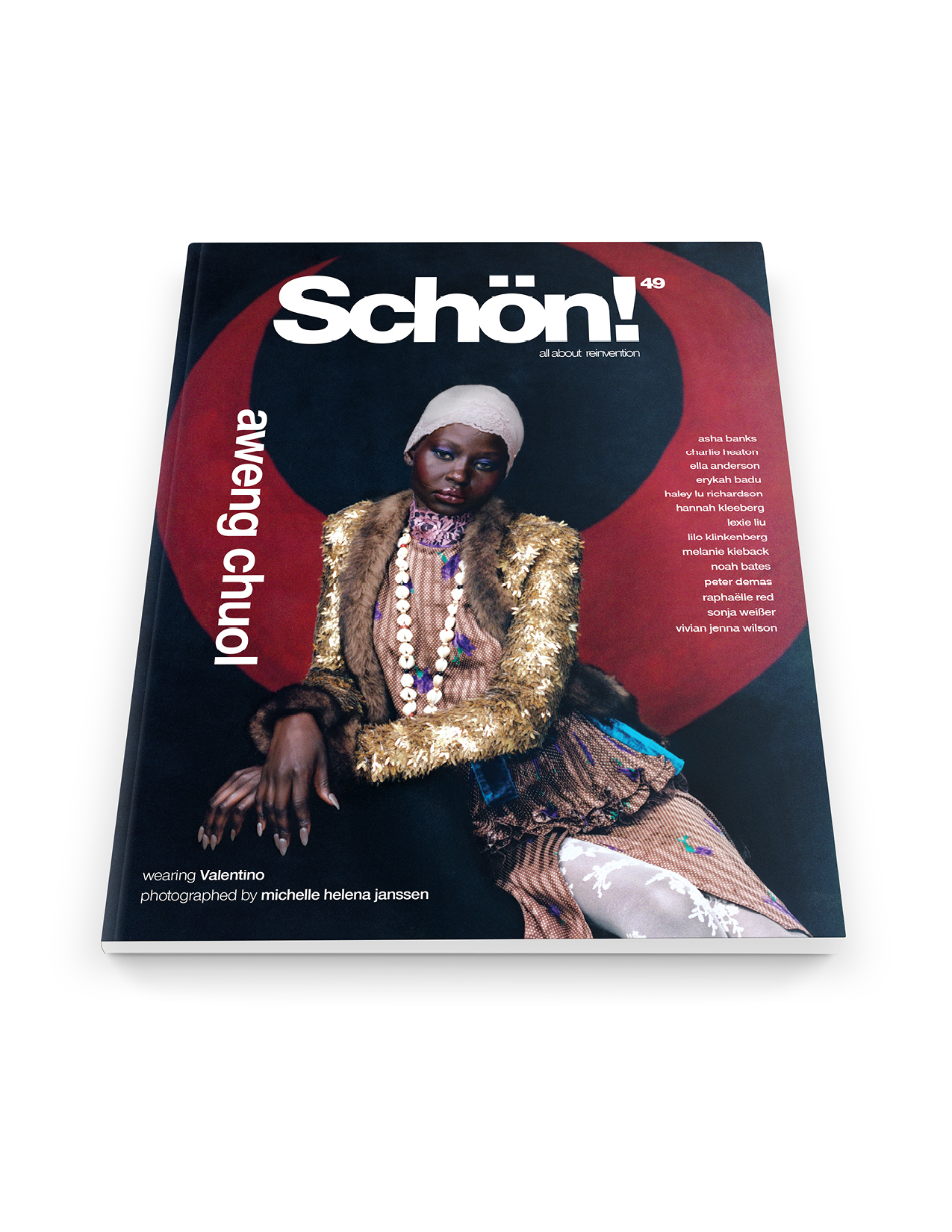

Schön! Magazine is now available in print at Amazon,

as ebook download + on any mobile device