Sometimes food is more than sustenance. Sometimes it’s the memory of a homeland or a person held dear. Chef Chet Sharma shares the inspirations behind his heartfelt cuisine. British Indian chef Chet Sharma’s spin on Modern Indian cooking has been making waves in London’s restaurant scene since BiBi opened to critical acclaim almost four years ago.

One could conclude that the progressive, contemporary techniques employed at BiBi are the result of the Chef Patron’s extensive experience working in some of the most exacting kitchens in the world. Or, perhaps, they are influenced by his formidable academic background in the sciences. To say that Chet (Chetan) Sharma has, in his 37 years, already lived a life less ordinary would be an understatement. The Berkshire-raised boy was born with a lung condition, which meant he spent limited time playing outdoors.

Instead, he filled his hours watching his grandmother cook and immersing himself in books (he now owns an impressive collection of over 1,200 tomes). It’s not surprising then that he excelled academically but, with a Bachelor’s in Chemistry, a Master’s in Neurology and another Master’s and a DPhil in Condensed Matter Physics, perhaps the last place you’d expect to find him is in a kitchen.

Yet, in his youth, Sharma completed a staggering 16 stagiaires in Michelin-starred restaurants, including Dabbous and The Fat Duck, before going on to land positions at establishments like Le Manoir Aux Quat’Saisons, Moor Hall and The Ledbury. But the real inspiration and drive behind BiBi stems from something altogether different. The restaurant is an ode to both his grandmothers (in Urdu, BiBi is an affectionate term for grandma), and its influences are firmly rooted in nostalgia.

Schön! alive is intrigued to find out more.

Chet Sharma.

Chef Patron at BiBi London

bibirestaurants.com

photography. Anton Rodriguez

How did you go from a PhD in physics from the University of Oxford to becoming a chef?

I didn’t always want to be a chef. It sounds simplistic, but I just love cooking. Food gives me a way to explore my own heritage, my culture. It also gives me a creative outlet that the sciences never did. In our culture, we’re surrounded by food from an early age. The very first thing they give you when you’re a newborn – the day you’re born – is a spoonful of honey from a local beehive, which they will now tell you is the worst thing you can give to a baby, but it’s a very old tradition. Even my nieces and nephews have been through the same treatment. It’s supposed to help, from an old, pre-science thinking about allergies, maybe? I don’t know, but maybe this is why people don’t have allergies in India.

So, it’s about the health benefits as well?

Food’s such a big part, not just to bring together communities in India, but from a medical point of view as well. We still use some of those principles in the restaurant here, where we look at old ayurvedic practices: what you should eat, when you should eat, what spices do, what the balance of spices is, because that’s where a lot of the old recipes come from. Delhi was the old capital of the Mughal empire, and one of the physicians said to the emperor that he needed to eat more spicy food to counteract the bad water from the river, so that’s where this whole thing of using lots and lots of heavy spices in Indian cuisine came from. There are many examples of using food as medicine. Food isn’t just something you sit down and eat when you’re around the table. It kind of dictates everything you do in life as a North Indian, especially one with a farming background.

Is it true that you also worked as a DJ at Ministry of Sound during your studies?

Yeah, so it’s a bit of a weird one. I’d do the dinner service at a restaurant, finish anywhere between 11 pm and 1 am and then go and do a set at a nightclub. I had this pumped-up energy and desire for creativity, which I maybe didn’t fully understand at that time because, when you’re a young chef, you’re just executing other people’s visions. The music side was honestly a lot of fun, as you can imagine, being 18 years old and a DJ at Ministry of Sound. I did New Year’s Eve at Wembley Arena once, which was pretty special. It’s funny because journalists pick up stuff like I DJed alongside Kanye West and 50 Cent. Well, technically, yes, but as a warm-up to the warm-up act. There is a video, though, of me dancing on the stage with Sean Paul!

clockwise.

Ikejime Trout + Plantain.

Cornish Native Lobster with

peanut + sesame salan.

Chamba Chukh Turbot.

photography. Anton Rodriguez

BiBi was meant to open in 2020 but then, of course, there was the pandemic. How did you handle that?

The pandemic was a horrible period for everybody – people lost family members, lost their jobs – and just horrible for our industry, which has still not fully recovered. But, in some ways, it was one of the best things that could have happened to me. Not being in service basically for a year before opening this restaurant really gave me a sense of perspective for the work-life balance for the team. It made me look back to when I was a junior, the hours I put in. I was just knackered all the time and a zombie on my days off. Now my body’s accustomed to it, but that’s not what I want for my team, for the people here who make BiBi what it is. And, on the other side, eating in restaurants is an important part of a chef’s job.

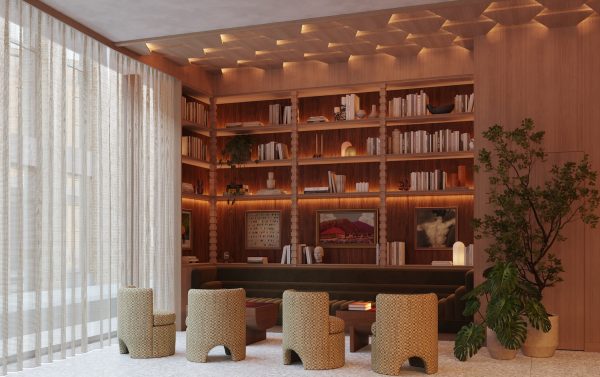

What did I miss about hospitality, about restaurants? That’s one of the reasons we slanted more casual with the style of service here. I mean, we take it very seriously – we just take ourselves a little bit less seriously…even in the music, the vibe of the room, we joke around and have fun with our guests. I hope we’ve created a very warm space, because at the end of the day, our jobs as custodians of hospitality is to look after people, look after our guests and our team. The interiors also create that warm environment.

They were influenced by your grandmothers, is that correct?

Yes, some of them were lifted directly from my two grandmothers. One of them had loads of pashmina shawls and saris, so we worked with a mill up in Huddersfield that recreated all those patterns, and they line the back of the chairs and some of the walls. And from the other grandmother, we got so many design ideas. She had this amazing colonnade in her farmhouse with these lovely arches, so the mirrors at the top of the counter kind of mirror that and then the beaded curtain at the back is actually from her farmhouse; it’s the one she used to have.

The sound of that beaded curtain really annoyed everyone when they first started working at BiBi but, every time I hear that, it transports me back to when I was a kid. The sound’s very nostalgic for me. In the same way, we light incense, because both my grandmothers were very religious, so they’d light incense every morning. The smell of incense is the smell of home to me.

How do you combine those nostalgic or more traditional elements with a modern approach?

It’s a great question. What we try to do in the restaurant is a bit of a juxtaposition. There are some elements of classical Indian design and then there’s conceptual modern art on the walls. There’s the mango wood counter, for example, the antique brass lights, but then you’ve got super rustic plateware that’s made by potters here in the UK; hand blown glasses that are super fine, but then we’ll serve you water in a recycled glass. It’s all – in a positive way – a little bit mishmash.

And does this approach extend to the menu?

Apart from the fact that you’ll probably be getting Lahori chicken – because that’s the only dish that doesn’t change on the menu – I want people to come in and not know what to expect. And, what’s nice is that most people with South Asian heritage will say that 90% of the menu they don’t recognise, but there’s this one moment that transports them: the ‘Ratatouille’ moment. This daal, or the roti or the chutney – whatever it is, there’s this one element that they walk away saying was super nostalgic. Sometimes they can’t even pinpoint why, but as soon as they eat it, they are like, “This tastes like something and I have no idea what it is, but it’s taking me back to India.” And, whether it’s India, or Pakistan, or Sri Lanka, those moments are really important for me.

Tell us about the grains, because the ones you use, for the rotis, for example, seem quite specific and not the standard stuff you could maybe buy here.

So, again, some of it is nostalgic. The first time I smelt Paigambari wheat being milled, it took me straight back to my childhood, because my grandmother used to mill wheat every day for her flatbreads. And, honestly, it only takes one person to validate that decision and to go through all this trouble.

We had these two Sikh Punjabi brothers… They were from Canada, but they were on their way back from scattering their grandmother’s ashes in Punjab and they stopped because the restaurant is called BiBi (grandma). They broke down in tears – I mean big, burly guys with beards and turbans. They’re a warrior caste, right, but they broke down in tears and said, “This wheat is my grandmother’s wheat, and this is what it tastes like.” That’s enough for me to say that wheat varietal will always be on the menu. So, yeah, the effort you go to for sourcing is quite extreme, admittedly. I have this policy of sourcing things from farms I visit in India. All that makes running the restaurant more difficult, but because of those two Sikh guys that day, it’s 100% worthwhile.

right

Calamansi Margarita.

photography. Anton Rodriguez

middle

Cold brew Osmanthus Tea +

Mysore Sandalwood.

left

Salted Kithul Old Fashioned.

Get your print copy of Schön! alive at Amazon.

Download your eBook.

words. Huma Humayun