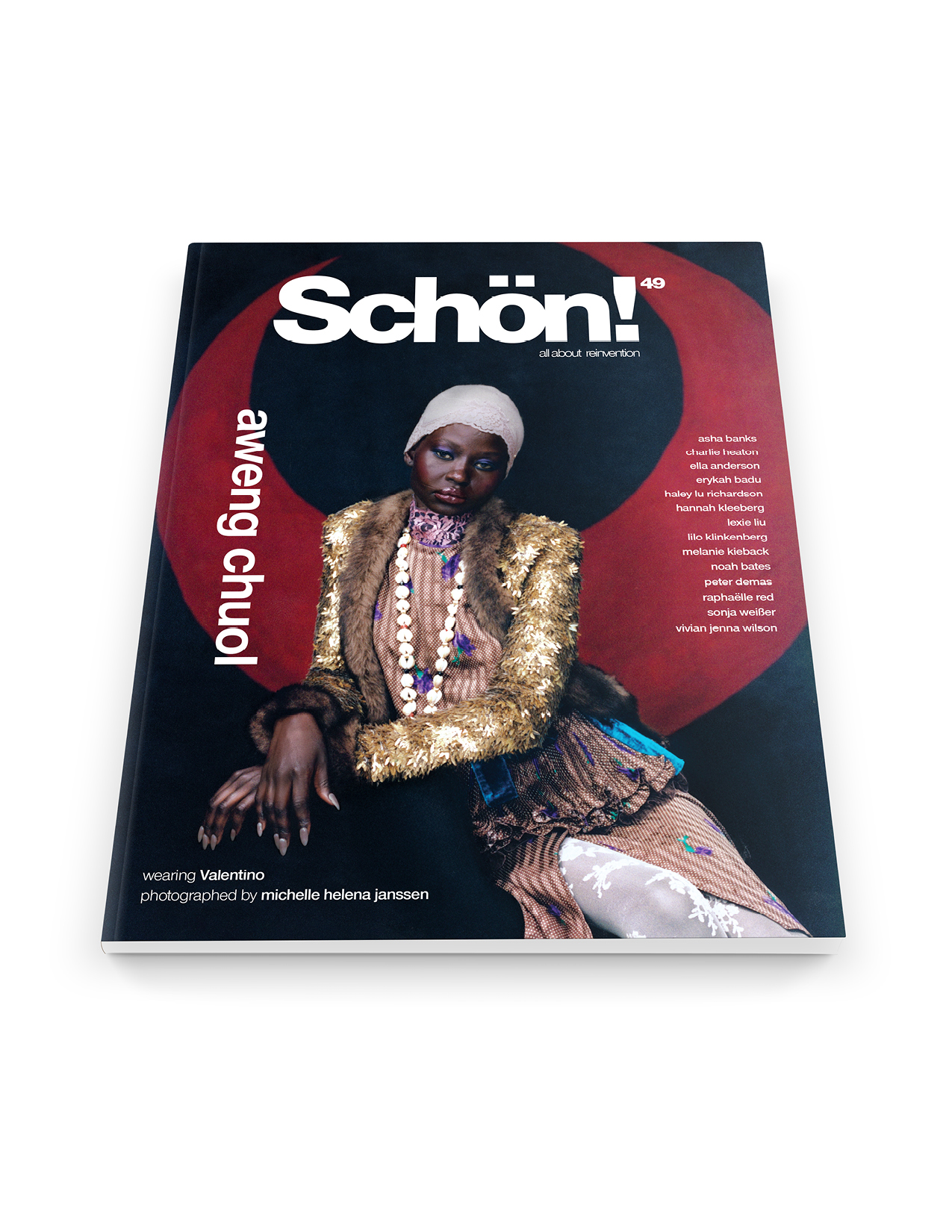

La Galerie des Magnums.

Wine cellars, Maison Ruinart.

4 Rue des Crayères, Reims, France

ruinart.com

For centuries champagne has been synonymous with celebration, but climate change is affecting how this beloved beverage is produced. Frédéric Panaïotis, Chef de Caves at La Maison Ruinart, shares with Schön! alive how the renowned champagne house is adapting to these shifts. Champagne has long been associated with joyous occasions, but the traditions behind its creation are now being tested by unpredictable weather patterns. Rising temperatures, harsher winters, and erratic seasonal changes are altering the growth cycles of vines, compelling winemakers to rethink their methods. In response, the industry is increasingly embracing sustainable practices to safeguard the future of champagne.

Ruinart’s winegrowers and winemakers have observed the accelerating impact of climate change firsthand. To counteract these effects, they have refined their techniques, adjusted their blends, and collaborated with startups to study the consequences on biodiversity. This proactive approach ensures that the rich heritage of champagne production remains intact while evolving to meet new environmental realities.

Born in 1964, Frédéric Panaïotis developed an early appreciation for viticulture in his grandparents’ vineyards. Immersed in the art of winemaking from a young age, he pursued formal education at the Institut National Agronomique Paris-Grignon, specializing in Viticulture and Oenology. He later earned the Diplôme National d’Œnologue from the École Nationale Supérieure Agronomique in Montpellier in 1988.

In 2007, Panaïotis joined La Maison Ruinart as Chef de Caves, where he became responsible for crafting the house’s signature blends. His expertise extends across Ruinart’s portfolio, from the non-vintage Blanc de Blancs and Rosé to the prestigious cuvées of Ruinart, Dom Ruinart, and Dom Ruinart Rosé. Under his guidance, Ruinart maintains its commitment to excellence while integrating innovative approaches to combat climate change.

As Ruinart navigates the evolving landscape of champagne production, Panaïotis emphasizes the importance of balancing tradition with forward-thinking strategies. By respecting time-honored techniques while embracing sustainable solutions, Ruinart ensures that future generations can continue to savor the magic of champagne. The world of champagne is changing, but its essence remains. Through dedication, innovation, and a deep respect for the craft, La Maison Ruinart is leading the charge in preserving this timeless beverage for years to come.

clockwise.

Diane de Chevron Villette.

Cheffe de projet environnement & OEnologue

HABITATS.

by Nils Udo, 2022

The Taissy vineyards of Maison Ruinart.

Since 2014, these historic vineyards have

been certified High Environmental Value and

Sustainable Viticulture in Champagne.

Tell us how you got into the world of champagne.

I was born and raised in this region. My dad liked wine, and it grew in my family. My grandparents had a small vineyard, so when I was very young – around two years old – I was allowed a little sip of champagne every now and then. As I got older and started to think about what I would do as a job, I studied biology and, even though it was not my initial wish, I naturally chose the path to study vineyards and winemaking. But what really convinced me is the people, not so much the product. We had this amazing trip to Burgundy when I was a student, and this old producer opened a jeroboam of Pouilly-Fuissé 1969. I remember he said, “I have four of them, but I’m opening one for you,” and I was mesmerised because we had no money – we weren’t going to buy anything – but the guy was so generous to open and share and show us what an old Pouilly- Fuissé tasted like. I think that’s what I like about wine. It’s about sharing, memories and friendship.

Can you tell us what a typical week looks like for you?

The good thing is that there’s no typical week or typical day. That’s what I love most about my job. There’s zero routine and because the season changes, you’re constantly learning. There’s always something new. I feel like it’s a big privilege that I don’t get bored, and I honestly can’t get enough of it. There are so many outside factors that make every day different, but there are also human factors. In the morning you’ll be wearing your boots and stomping through the mud, going around the vineyards but then in the evenings, speaking to a crowd of VIPs in Paris about the vintage. clockwise

Nestled in the Nicolas Ruinart Pavilion, near

the Crayères, a secret cellar is home to

iconic cuvées and historic bottles of Ruinart

champagne, preserved as milestones in the

Maison’s history such as the

Dom Ruinart Blanc de Blancs 1961

What is the secret to making excellent champagne?

Grapes, vineyards and grapes again! That’s where it all starts from. Then teamwork, passion, dedication, and time to make champagne – because that ageing time is extremely important. Time is one of the essential elements of champagne, but the beauty is that you can drink it early on. You can also age them and discover another facet of the champagne. Is there some sort of mindset you enter when you’re working? How can you not be happy having this kind of job? I came across this Chinese saying: “Find a job you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life.” I’ve been doing this for 35 years and not once have I felt like I’m working.

Desnatureza 6.

by Henrique Oliveira, 2024

Open to all, 4 Rue des Crayères

offers an immersive experience of

art, history and bespoke champagne

pairings crafted by acclaimed chefs.

How is climate change impacting the production of champagne?

It brings new challenges. The grapes are ripening faster, the cycle of the vine is shorter, and it brings a different balance in the grape. So, we had to reinvent and re-adapt ourselves to the new conditions. We’ve proven with Le Saint-Golier that we can still make great champagnes even in the craziest, warmest year on record, which could be the norm in 20 or 30 years. It showed that we have the capacity to adapt because we still have water, which is obviously one of the most important things when you deal with plants. And we have the knowledge.

What we’ve done [is] based on a know-how that’s decades – even centuries – long. We know how to adjust and slightly change to the new parameters and still make champagne that is very appealing and enjoyable with this kind of softness, nice texture and with a beautiful, fresh balance. Even though the climate is changing in our region, we can manage for a few decades. That could probably not be the case for other regions that are exposed to extreme drought. South of France, Italy, Spain…some of the areas might disappear in the near future. In Champagne, we still have some future, but we need to rethink and be ready to change a few things.

Do the other houses think this as well?

We are lucky in Champagne to have this amazing committee that equally integrates the houses and the growers. So, we work together. We’re on the same boat, so we go in the same direction, and I think most people are very progressive about it. When you work with nature, you really see climate change. It’s not through books or Instagram stories or the news. It’s the reality. You deal with it. I think people in Champagne are fully aware how precious the name is.

Champagne is apparently the second most known French word in the world after Paris. Everywhere you go – to any country in the world – you say Champagne and people know what it is. That’s not the case with Camembert, for instance! We know our name is an amazing treasure, so we need to protect it. We need to protect it by making sure there’s no copy using our name, but also by making sure that the land stays the same for as long as it can, that we are sustainable in everything we do, from growing, winemaking, shipping to packaging, etcetera. I would say that maybe not all, but a high majority of producers, are fully aware of it.

What was the most significant thing you’ve learned since starting this position?

I realised that I don’t know so much! The cool thing about this job is that you keep on learning, which keeps you fresh and young. The other thing I’ve learnt is that you need to be in love and in harmony with the company you work for, sharing the values and the tastes as well. Here I feel at home.

What makes Ruinart special compared to the other houses?

We have this incredible mix of modernity and tradition. We express it in many ways, but we also express it in wines. We are the oldest champagne house. We were the first to make rosé back in 1762. We’ve been innovating since the beginning and have been the first in so many fields. Today the style of our wine is not old school at all. It’s actually amazing. We use modern technology to make our wines more precise. So, we really have that tension between tradition and modernity in every aspect of the house and I think that’s what makes it so special and so successful. If you’re modern with your style, it means you change it all the time. The Blanc de Blancs you taste today is different from the Blanc de Blancs that we made ten years ago, because we are living with our world and adjusting to new conditions. Also, we’ve been disruptive. The second skin packaging, for example, was a little revolution. It’s part of the DNA of the house to innovate.

What do you bring to a 300+ year history? What’s legacy to you?

I feel like it’s easier to go away when you’ve left something tangible – whether it’s a book or a piece of art – and we’re lucky because we leave bottles for the next generation. Rebuilding the library is a huge pleasure because I know that, in the future when I retire, someone, somewhere will enjoy it.

Bottles of Ruinart in the innovative, authentic and

environmentally conscious Second Skin Case.

ruinart.com

Nicolas Ruinart Pavillon.

An exceptional space where every

guest is welcomed with bespoke care,

offering inviting lounges, a champagne

bar, a boutique, and a terrace for a bright,

immersive experience.

And what is most challenging about part of your job?

Climate change. We see the effects. We’ve seen them for the last 25 years and it’s bringing new issues. For example, we’ve had to adjust and change the recipe for the rosé because of the grapes ripening early. And not only learning how to react, but how do we play in our role towards sustainability as well? We’re taking so many actions, like how we can reduce packaging yet ensure it still looks luxurious.

What advice would you give to someone wanting to enter the industry?

Be passionate and be humble, because wine is a lot about humility. It teaches you humility and it’s hard.

And what’s the most rewarding part of your job?

When people smile and are having a good time. That’s honestly the best reward. I have friends or customers send me pictures of bottles they’ve enjoyed, and they’ll say ‘Fred, thank you,’ even sometimes when I’m not responsible for a particular bottle! Like someone once sent me a picture of 1990. I wasn’t even there! But you feel like you gave them some pleasure. This kind of recognition is the greatest reward I can get. There’s two ways of seeing my job. As a cellar master, my job is to make wine according to the style of the house, and in that way, I’m the guardian of the temple. But the other way I see my job is to make people happy. I’m bringing pleasure to people. And how many jobs in the world do that?

clockwise.

Fenêtre sur vignoble.

by Ugo Gattoni, 2024

Cerf Contrôle.

by Pascale Marthine Tayou, 2024

Serpentine Bell.

by Tomoko Sauvage, 2024

left

Retour aux sources. art installation

by artist duo Mouawad Laurier, 2019

right

Chateau of Maison Ruinart.

mirrored in the Nicolas Ruinart Pavillon

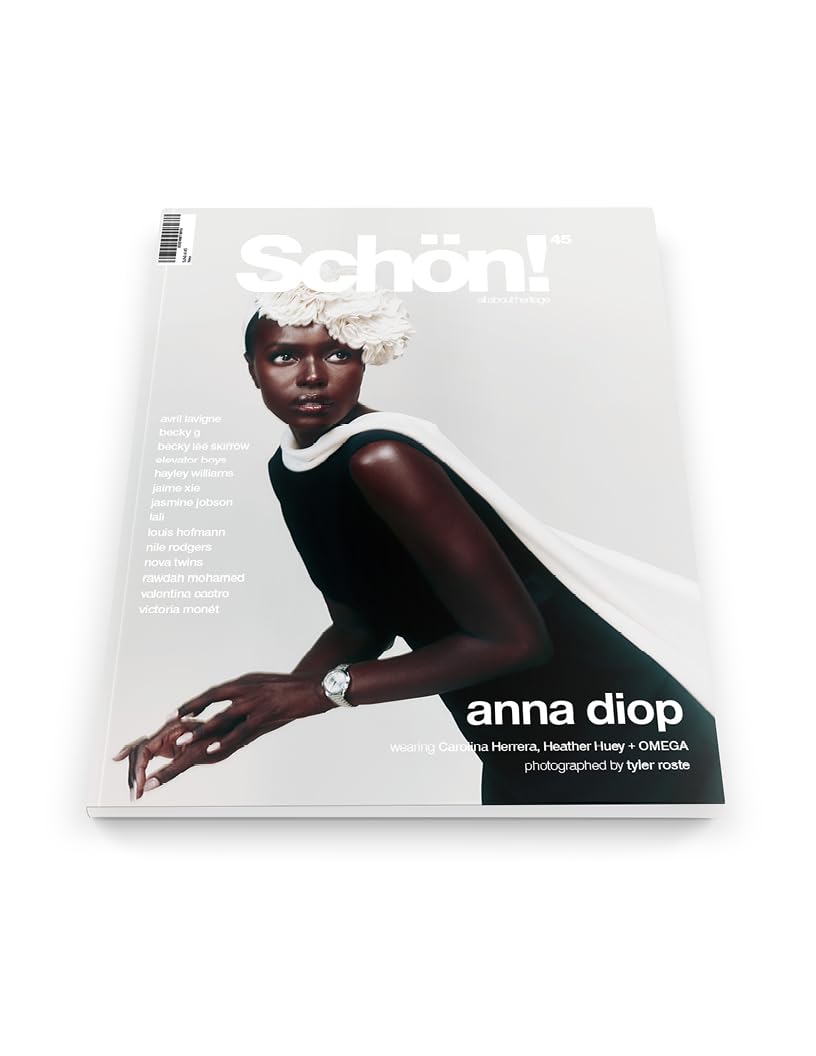

Get your print copy of Schön! alive at Amazon.

Download your eBook.

interview. Raoul Keil

words. J. Bibi Cooper

photography. Simon Lipman