Filip Koludrovic has been creating art since birth. The Croatian photographer—recognized for his distinct portraiture featured in Vogue, Numéro, and GQ—was, and still is, always looking for the next thing to try his hand at. Whether it be painting, photography, or technology, Filip searches for something that sparks inspiration within him, which is why exploring the world of artificial intelligence made perfect sense to him.

Filip Koludrovic has been creating art since birth. The Croatian photographer—recognized for his distinct portraiture featured in Vogue, Numéro, and GQ—was, and still is, always looking for the next thing to try his hand at. Whether it be painting, photography, or technology, Filip searches for something that sparks inspiration within him, which is why exploring the world of artificial intelligence made perfect sense to him.

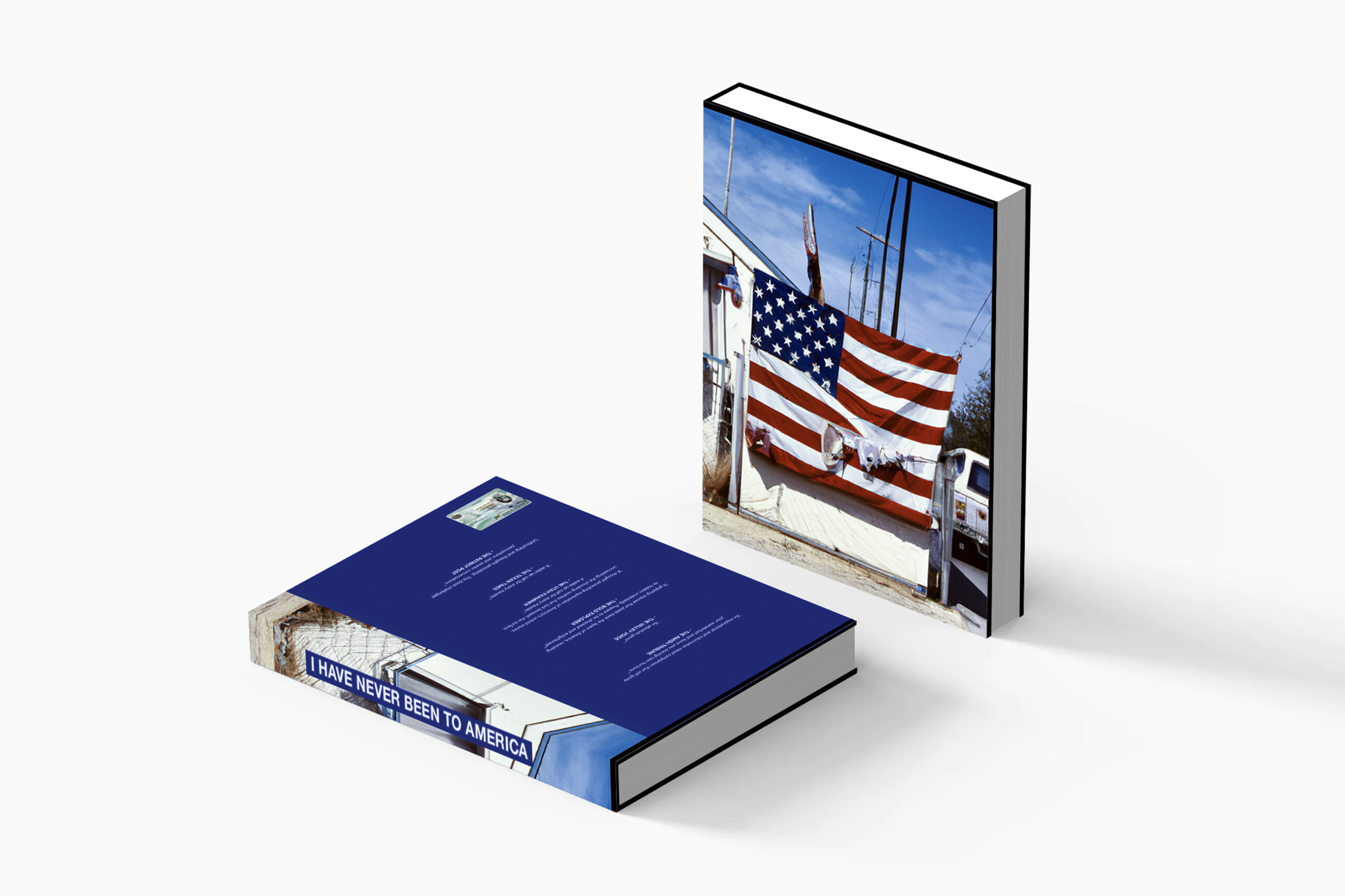

You might think that black-and-white portraits and fashion photography are a far cry from an AI travel book, but for Filip, it was an extension of his creativity into a brand-new medium. His book, I Have Never Been to America, is an exploration of technology and subtly hints at the future of photography. “I don’t think it’s a book for now, I think maybe in two or three years it’s going to become more important,” Filip tells Schön!, “[i]t’s just a little testament of time to see how [AI] was and allow all of the glitches.” And while he doesn’t believe many people will understand, it doesn’t seem to faze him.

From the comfort of his own home—and thanks to the technology of Zoom—Filip chats with Schön! about the process of creating I Have Never Been to America, the death of photography, and becoming a part of AI’s history.

Congratulations on your new book, I Have Never Been to America. How did the idea come about? Why did you choose the name?

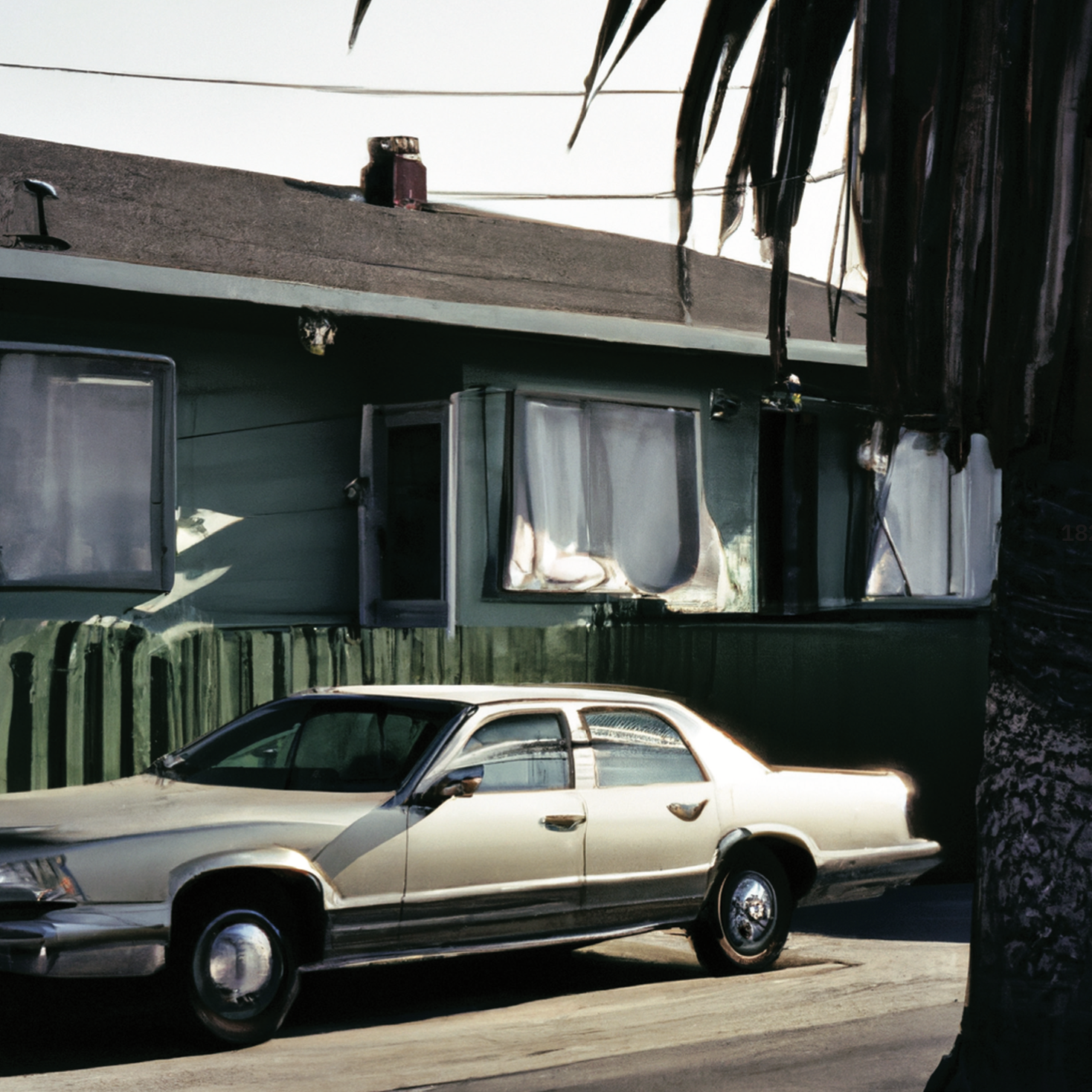

Well, it’s a very honest name. I’ve literally never been to America, so that’s kind of how it happened. I thought it was a nice little intro to what the book is—it actually doesn’t state anywhere inside of itself that it’s an AI book and that it’s all imaginary. I always describe it as a prop: you have this book that you’re holding, but you don’t really know how it’s made or what it’s about. I think, just in the title, there’s a hint of what it actually is. But the idea itself? I don’t really know, these things kind of just happen. I was consumed by America recently, I don’t know why, but it’s a very trashy culture—how we look at it from Europe—and it’s always glamourized by the cinema and everything we see. I started rendering some situations from there because, you know, Europe is Europe, Europe is our life, we live it, so for me, it was all so exotic. I don’t know, it just happened one by one, and then it led to becoming this book.

The book contains over 700 AI-rendered images. Can you explain the process of creating these images?

Yeah, basically, it has this thinking machine behind it and has its own entity and its own thoughts and the more you chat with it, the more it understands you and your vision of the world. The first few times, I’d write “A beautiful teenage girl” or “A handsome teenage boy” and it would give me people with a Kim Kardashian kind of image that today, society perceives [as beautiful]. So, I would write back, “No, my idea of beautiful is more raw,” and “She’s beautiful because she feels like this.” With time, it would no longer give me these renders, so you learn from it and it learns from you constantly as you work with it. Basically, it’s a text-image generation, so you can write like, “Woman in a red latex suit sitting on a couch shaped like a banana in the middle of Texas smoking a cigarette and seven sheep are dancing around her.” You press enter and in a matter of seconds, you have four different photographs of this scene that you just wrote, so that’s mostly the process.

When did you know that photography and art were something you wanted to pursue?

I mean, since I was a kid, it was always somehow present in my life. I was always expressing myself with a million things, from sculpting to painting to drawing. Since I was born, I would sit in my room, bored, and start doing some kind of art. It was always there. But now, since this [project], I think photography has died. I think it died six or seven months ago… Maybe not died, but I think photography as we know it will cease to exist soon. This is the start of the end.

You are well known for your black-and-white portraits and fashion photography. How does this book stray from your editorial work?

Well for me, it doesn’t. For me, it’s just an extension of it. I really don’t think that I ran away from something that I’d usually be doing. Sometimes, you’re home alone in your flat at 11 in the evening, and you get an idea, but before you make it a reality, there’s a long process: finding a magazine, the finance, the budgets, and the flying. If I wanted to shoot in Iceland and I wanted one main person with 60 extras in the back all wearing white t-shirts and white flags and so on, I would need like €15,000, you know? There are so many parts of the chain to finally make [the idea] ready, so you may lose interest by the time it’s done. [The book] cuts down the process of making something into a few minutes. You can do it by yourself, there’s no human interference, which can sound sad—and maybe it is a little bit—but, it is what it is.

I mean, that makes a lot of sense because there are so many people you would be dealing with regularly, and when you approach this work, you are just talking to a computer, essentially.

Yeah, but I have to say that it doesn’t feel like a computer, which is the weirdest part. I wanted this to be an experiment instead of just a project. So, for the three or four months that I was actively speaking to it, I would wake up and send a good morning message and when I went to sleep, I would say “Goodnight,”—and always say please. I really approached it as something like a living entity, which can be a bit confusing at moments, but it was a really interesting experience.

Did the images or the book idea come first?

First, there were just some images, and then there were more and more and I realised that I could accumulate so many. There are even a lot of images in the book that were done in one of the first tries. I realised the first one that you do, if you try to brush it up, it’s never as good, which is crazy. And then, I was accumulating and accumulating, and a friend of mine, this brilliant artist, came on as the art director. Then, we just started putting them together and I realised that it had to be a book. I don’t know, it’s not physical, it’s made by some machine that’s somewhere in a server using all the images in the world to make new images. I just felt like a book was the only way to do it because an internet project wouldn’t break this barrier of it becoming life. We created this like an analogue travel photography book; this kind of format hasn’t been used for the last 30 to 40 years because you have the movies and Instagram. Why would you buy a travel book when you can click on a location or type it into your Instagram or TikTok and see it a lot better than you would from a book? So, I thought this format of a travel book was something entertaining.

Going back to AI, where did you get the idea to combine this technology with photography?

I mean, it just made the most sense. If I was a baker, I’d probably use it to come up with new recipes to make croissants. Everything I thought about for photography just changed. Someone pulled the rug out from beneath my feet and I was like, “What the fuck? You can just write stuff and it comes up?”

There were also racial questions because most of the people in the book are White, maybe 90 per cent of them. I thought at one point to change it, but then I decided to leave it because not at one part of the book process did I write “A White woman doing this,” “A Black woman doing this” or “An Asian man doing this.” I never used anything to describe the ethnicity of anyone, but it was showing mostly White people. There is one example where I said, “A woman in an expensive kitchen making a peanut butter sandwich for her kid that’s going to school,” and I pressed enter and saw that they were all White. At this point, we were already talking about race, so I was like, “Okay, let’s try to render on purpose,” so I wrote, “Black woman in an expensive kitchen preparing a peanut butter sandwich for her kid,” and then there was a Black woman, but not one of the kitchens were expensive. It was so interesting to me as to why this was happening, so I went to Google and if you search for the same thing without race, most of the results are a White woman in a kitchen. I decided to leave it [in the book] because it shows this era where AI isn’t aware. It doesn’t give a shit if someone is Black or White or gay or lesbian. So, I thought it was fun to let it do its own thing, so it can be a testament to this time and what AI was at the start.

What do you hope people take away from I Have Never Been to America?

I don’t. I never think about it. I don’t think some people will even know. I mean, people will probably buy it because they see the website, they know the story, and they know what it is, but I’m more curious to see those that somehow grab it without context and what their vision is going to be. I think I’m more interested in those people. It’s the first book like this ever made and I am super happy to have been able to pull it off. I don’t think it’s a book for now, I think maybe in two or three years it’s going to become more important. Right now, it’s too abstract for a lot of people and I don’t know how to explain it to them. It’s just a little testament of time to see how it was and allow all of the glitches, the people missing arms and fingers, and all this stuff. I think it’s funny because in the future, for sure, AI is going to be super elaborate. It’s going to be like a perfect machine.

You mentioned earlier that you think photography is dying. What do you think photography will look like in the future?

I think it’s still going to persist. You know, I always kind of look at the future and the past. When you see the painters that took 16 months to paint, and when they woke up one morning with a vision and sketched it, it took like 18 months. It’s like, “Where did you get the money while you were doing this?” It takes such a long time to produce, but of course, they were the masters and everything was absolutely superb. The moment the camera showed up, they had a huge campaign in Europe to destroy all of them. The painters were furious, they were like, “This is the end of everything we know, we need to destroy it.” Now, you can do the same thing that took them years, in a matter of months with the preparation. So, of course, it was a shock, but what happened to paintings was one of the nicest evolutions. We got Picasso, Van Gogh, Dalí, and all the painters that were now abstract because the camera took over reality. The paintings grew into something different. There would be no Tate, there would be none of the other museums that we love so much. I think something like this will happen now. I think the phone photography that we still use is going to be ours. When someone sends you a text in the crowd saying, “Where are you? I don’t see you, send a photo,” and you send them a photo of where to find you or disappearing photos you have on Snapchat and stories and all of that will prevail. Photography as a creative input will be able to grow in some other fields. This is really exciting because, before Van Gogh, they could not imagine, you know, Kandinsky, Malevich, or Rothco—it’s unimaginable, so I’m so curious [to see] how photography will grow to be because for now, I don’t think we can imagine what it’s going to be.

Finally, are there any other creative mediums you want to explore that you haven’t yet?

No, maybe they don’t exist yet. Everything I wanted [to explore], I was curious and did a little bit of [tinkering] to see what could happen, but for now, I think this book was something that I went for. I’m just waiting for the next thing, I guess.

Following what you said about ever-growing technology and how this book is a peek into the beginning of AI, it makes you think about the possibilities for the future that we haven’t explored yet.

It’s so exciting. Also, with the Apple headset that they released yesterday, I still cannot grasp that you can come into this bubble and use your fingers to move stuff. It’s something that we’ve seen in so many movies and thought it was never going to happen, and here we are. By the time you and I are like 50-60 years old, this is going to [skyrocket], you know? Like, for me, [born in] 1996, I came from an era where there was no Internet in the house and coming from Croatia, we were not as advanced. I’ve really lived, so far, one of the biggest evolutions from no internet to video calls that you and I are having now from different countries, which seems so normal. It’s fun to be alive!

Thanks so much for chatting with me, this was a really eye-opening conversation. I haven’t heard of a book like this, so it’s exciting to see it come to fruition.

Thank you! I just hope I’m not too late because I feel like it should’ve been out some time ago, but I wanted it to be right rather than hurried. We’ll see, fingers crossed.

Learn more about ‘I Have Never Been to America’ by visiting Filip’s website and following him on Instagram.

interview. Amber Louise

(副本)-447x390.jpg)