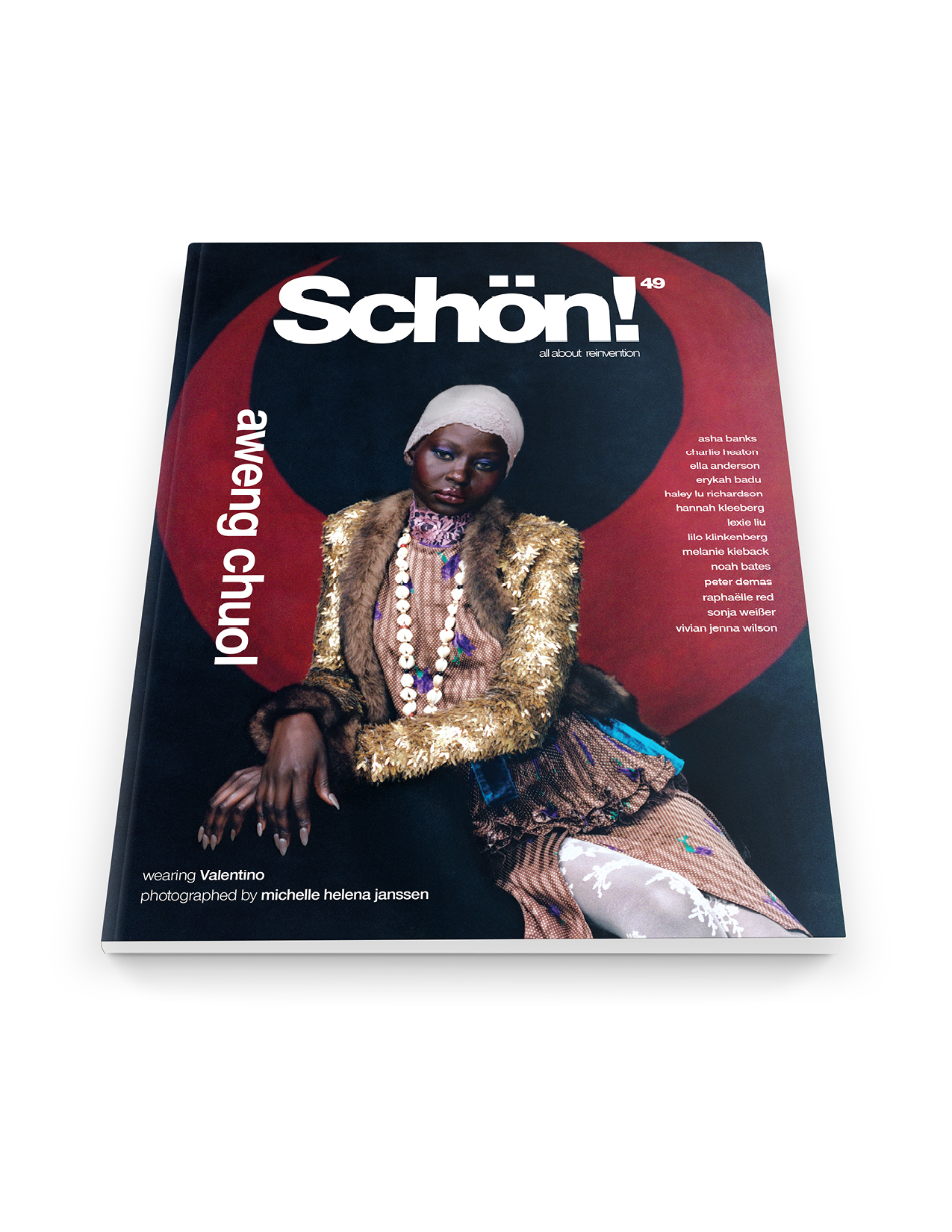

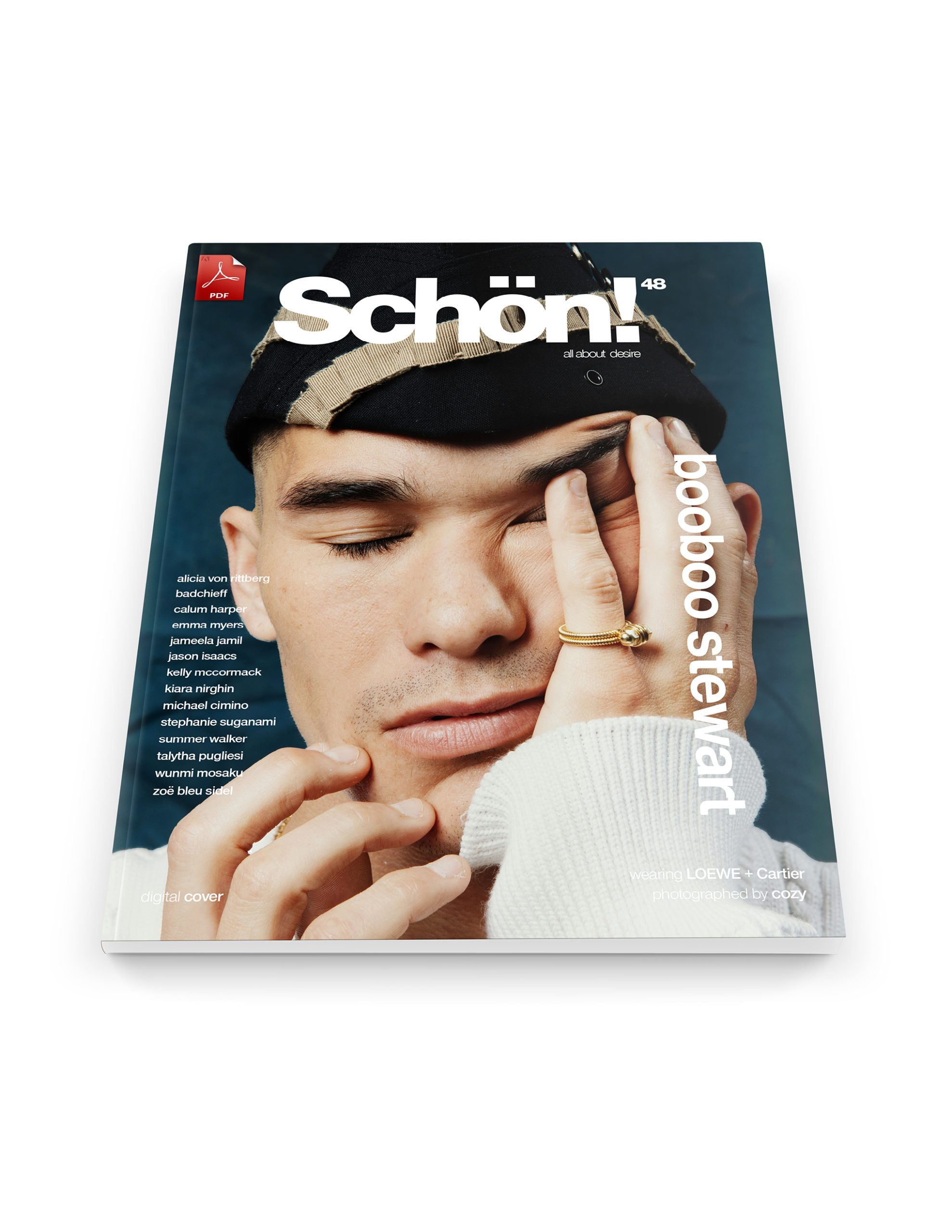

Head Chef Frederick Forster at 190 Queen’s Gate

For Frederick Forster, food has always been both inheritance and evolution. A Roux Scholar, National Chef of the Year and Master of Culinary Arts, he has spent over three decades shaping British fine dining from the inside out. His path, from his mother’s West African kitchen to the pass at The Ritz, and now to the helm of The Gore’s relaunch of 190 Queen’s Gate, tells a story not just of mastery, but of quiet endurance.

Having trained under legends like Michel Roux Jr., Raymond Blanc and Gordon Ramsay, Forster’s cooking carries the precision of classical French technique and the soul of lived experience, but behind the accolades is a chef who values patience over speed, substance over spectacle and humility above all else.

We spoke with the award-winning chef about the influence of his late mother, his philosophy on food in a trend-driven age and what legacy truly means after a lifetime in pursuit of perfection.

Fish & Corgette Flower

Your journey began in your mum’s kitchen and took you from Calvin Klein campaigns to Michelin-starred brigades. How did those seemingly opposite worlds shape your sense of artistry and discipline?

I never like to spend too much time talking about my modelling days, but it always, invariably comes up at some stage. It was something that I kind of fell into and enjoyed. I think, more importantly, my late mum was my biggest inspiration for food. She was definitely the lady who saw something in me from a very young age, before I saw it in myself. She would always encourage me to go shopping with her, understand how to pick out good produce and help her in the kitchen. I think my love of cooking and passion for food really stem from my mother.

In terms of the fashion world and the cooking world, I think a lot of people would say that the two go hand in hand to a certain degree: there is a lot of flamboyancy. The fact that I was able to be on the runway and do campaigns gave me confidence in myself, for sure. I think that translates to the confidence that I have as a chef.

Head Chef Frederick Forster

You’ve cooked everywhere from Barbados to Dubai. How has that influenced you?

I started my career young, and I’ve been lucky enough to work for some incredible chefs around the world. I’ve tried to take some form of inspiration, knowledge and training from that. Throughout my career to date, there have been a lot of things that I’ve been very happy about that I’ve achieved. When I set out to cook, I never sat down and said to myself, “What do I really want to achieve?” I think it crossed my mind a little bit, but I think if I look back on my career today, a lot of things that I wanted to achieve, I have to a certain degree.

Now, it’s more that I get a sense of fulfilment in going somewhere that requires a bit more input and challenge. It’s wonderful where I don’t have to do too much because it’s already there, but I think sometimes when you go somewhere that doesn’t have the resources that you’ve come from, you have to dig a little bit deeper. You have to be a bit more patient. You have to teach more. Working at these places has helped me get to a place like this now, which has a rich history behind it.

À la carte menu at 190 Queen’s Gate

What story do you want this re-opening to tell through its menu and atmosphere?

The Gore is a quintessential British hotel. It’s been around for a number of years, and it has an incredible reputation. We are not trying to reinvent the wheel. It’s more about a new chapter of The Gore. They haven’t had an à la carte menu for maybe four or five years now due to various reasons. I just want us to be able to have that offering now. I want people to be able to come here and enjoy lovely, delicious food made with high-quality ingredients in a pleasant, inviting environment.

Classical French training is your foundation, but diners today are chasing novelty and fusion. How do you balance respect for tradition with the pressure to constantly reinvent?

I think we’re at a stage now where people, whether we like it or not, are very much influenced by the social media type of food. I would say I’m a bit of an old school sort of chef. I appreciate the fundamentals, foundation and basics. People can get a little bit lost in the fusion aspect. It doesn’t mean it’s going to be great. I’d rather have something that is a lot simpler, great produce, not too many elements, but delicious, than have something that is mixed in lots of different types of genres of cooking from around the world. It’s got lots of ingredients, but it has no real substance. It looks beautiful, but there’s no real base or flavour there.

I think when people come to where we are now, they have a good indication of what they’re going to get, and that’s why they probably do come here. Be true to your values, true to yourself and true to the customer base that you have.

At this stage in your career, what still challenges or even intimidates you in the kitchen?

At this stage in your career, what still challenges or even intimidates you in the kitchen?

Most of the challenges that I have are what I put upon myself because I’m constantly learning. You can learn from anybody. I can learn from my most junior chef to my most senior chef. Once you have that open mindset, I think that’s very important. I just try to challenge myself every day to be better. I know it’s a bit of a cliché, but I’m always trying to improve what I’ve done. How can I make that better? How can I make my team better? How can I create a better environment? These are the things that are important to me in terms of challenges.

You’ve mentioned Michel Roux Jr’s advice during a tough moment in your career. What’s the most meaningful piece of guidance you’d pass on to young chefs who feel they’ve lost their way?

Looking at my own experience, when I had that conversation, it was mainly because I’d fallen out of love with cooking. I was going through a very difficult time in my life, like a lot of people do, and you always lean upon people whom you respect. I always ask chefs who are coming through, “Why do you want to be a chef?” Usually, it’s because they’re very passionate about food and have a desire and hunger to want to improve and learn because there’s so much to learn. And I always tell them that they need to be patient.

A lot of chefs now want everything quickly. They want to get to that head chef status very quickly, and then they miss out on the fundamentals and the foundations of cooking, and that takes time; it takes perseverance, patience and self-belief. So, I tell chefs to try and be patient and to work hard, because you have to work hard in this industry as well and, hopefully, with those sorts of things in your armour, it can help you go further.

A lot of chefs now want everything quickly. They want to get to that head chef status very quickly, and then they miss out on the fundamentals and the foundations of cooking, and that takes time; it takes perseverance, patience and self-belief. So, I tell chefs to try and be patient and to work hard, because you have to work hard in this industry as well and, hopefully, with those sorts of things in your armour, it can help you go further.

Looking ahead, when people talk about Frederick Forster’s cooking ten years from now, what do you hope they’ll say you brought to British cuisine?

I never really look at myself in that kind of capacity. I think that over the years, when these awards are still being given out, they will inevitably look back at the past winners of these titles. I would like to go down as somebody whom people respected, for people to be able to look at me and say, you know, he was a great guy – he was a very good chef, but he was a great person; he could communicate very well. Those things would go a long way for me, rather than me being here as a great chef or a wonderful cook. I think that’s the kind of legacy that I want to leave behind.

I come from an ethnic minority. I never really talked about it, but it is quite important to me. Growing up, there were not many chefs who looked like me at the top, and I used to ask myself why. I think that’s quite normal. You look to people who look like you, in an area where you come from, to see what’s possible, and there were not many. If people look up to me and think, I would like to be like Freddy Forster, or to follow a similar path as him, that means a lot to me.

White Chocolate Mousse, fig compote, coconut biscuit

Read more about 190 Queen’s Gate, part of the Starhotels Collection, here.

photography. courtesy of The Gore

interview. Naureen Nashid