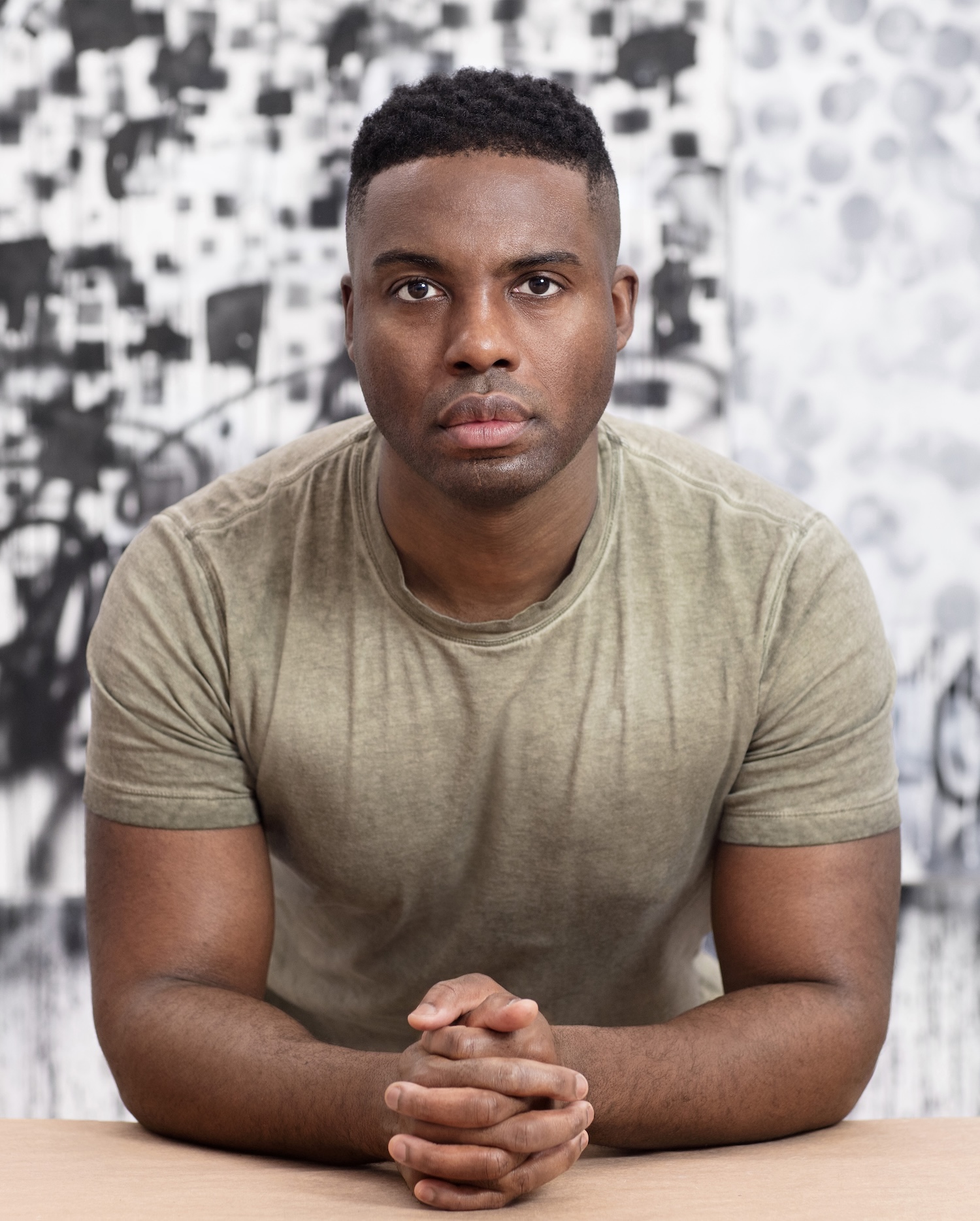

There’s a certain kind of quiet in Levi De Jong’s work. For De Jong, raised on the edge of his grandparents’ farm in rural Iowa, the language of art has always been tactile, provisional, and deeply personal. Long before he studied at the Royal College of Art or wandered through Renaissance chapels in Florence, he was building paper airplanes from scrap and suspending them over old industrial fans, trying to make them fly.

Now working across sculpture, painting, and works on paper, De Jong interrogates what America means not from a distance, but from within, through its textures, contradictions, and residues. His flags are tattered but intact. His sculptures shimmer with the weight of sacrifice. Whether mourning or mending, his work remains, as he says, “somewhere between protest and prayer.” In the ruins of national myth, Levi De Jong is not simply deconstructing America. He is remaking it, piece by worn, weathered piece.

Can you tell us about your earliest experiences with making, whether or not they were considered “art” at the time?

I grew up on an acreage next to my grandparents’ farm in Iowa, so there was really nothing else to do but make things and explore. I would always walk through the machine shed or back in the grove, and I was always fascinated by the treasures I would find.

My earliest experience with making is something I still think about quite often. I remember finding this old industrial fan and some newspaper. I couldn’t have been more than six or seven years old, and I began to fold the paper into a plane. I thought how great it could be to see the paper airplane suspended in the air, flying, all on its own. So I fastened a string to the center of the fan and the back of the airplane, and to my amazement, I got it to work, or at least for a few moments.

I think this kind of gesture really stuck with me. There was magic in it. I could imagine something and bring my dream to life. In some way, it is life-affirming. It reflects something true about us and the world. This is why art is so important.

Was there a specific moment when you realized art could be more than a visual object, that it could carry cultural, political, or emotional weight?

I was never introduced to art, really, until I moved to Florence in 2017, although I always had a hunch there was something that art could actually do, or did. My crash course was 16th-century painting and sculpture. It was all about the divine and nobility. I experienced the emotional weight of these great works through their sheer grandiosity and dramatic depictions, but there was always a feeling of separation between me and the works.

I then met a handful of classical painters who always talked about John Singer Sargent, obsessing over how he could render something so defining in a single stroke. Their fascination with technique sparked my own curiosity. I wanted to understand what made a gesture powerful, not just on a technical level but on an emotional or symbolic one. That led me to begin studying art movements outside of classical painting and sculpture. I became interested in movements like Arte Povera, Dada, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and eventually conceptual practices.

I realized there were artists who weren’t just rendering the world but interrogating it. They weren’t painting the divine. They were questioning the systems that claimed to define it. That shift in perspective showed me that art could carry a different kind of truth, one that held tension and could challenge rather than resolve.

How has your education in art either aligned with or pushed against the visual and material language you grew up with?

In Florence, I became a draftsman. In New York, I rediscovered the materials I grew up with. And in London, I was given space to make sense of both.

During my time at the Royal College of Art, I learned how to charge these materials I grew up with and to stop resisting my Americanness and instead step into it. I had spent time denying my upbringing, trying to become a European artist.

I think with the right amount of time and distance, I was able to finally examine certain ideologies, symbols, and truths of my childhood with a new gaze. I could hold them, examine them, praise and critique them all at once.

Were there particular artists, outside of the art-historical canon, who influenced you early on? Craftspeople, tradespeople, family members?

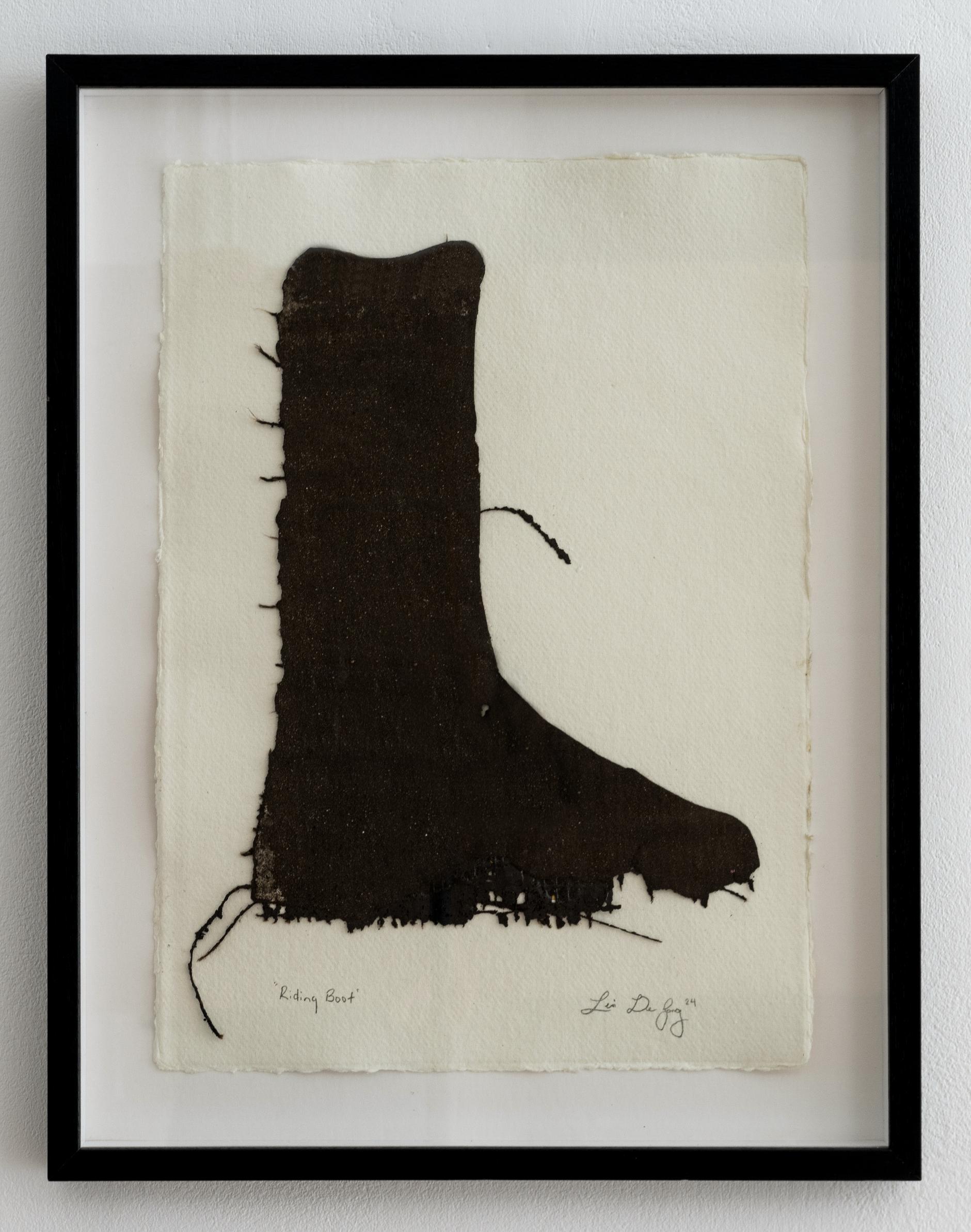

I grew up in a family of farmers and builders, so I was always around heavy machinery and an inherent ability to make things, anything. I then moved to Florence to become a shoemaker. I was quickly taken under the wing of a family of shoemakers who brought me along to their factories and studios, where I learned production, design, materials, craftsmanship, and the trade.

I also spent a lot of time with a handful of young designers studying at Polimoda. So my first influences were centred around patternmaking, draping, working with the stitch, considering proportions, how things should lay, colour, texture, and so on. This inevitably led me to fall in love with form itself—how material moves on, around, or in response to the body, and how precision can carry a feeling.

Your work suggests a deep respect for what is worn, weathered, or provisional. Has your view of what counts as “valuable” or “beautiful” shifted over time?

There is a graininess, a texture, a resonance that some people, places, and things are filled with. A curiosity, a wonder, a joy. I find beauty is always in the impermanence, the imperfection, the ebbs and flows, the cycles of growth and decay. I think I’ve always felt this, but my taste buds are always maturing.

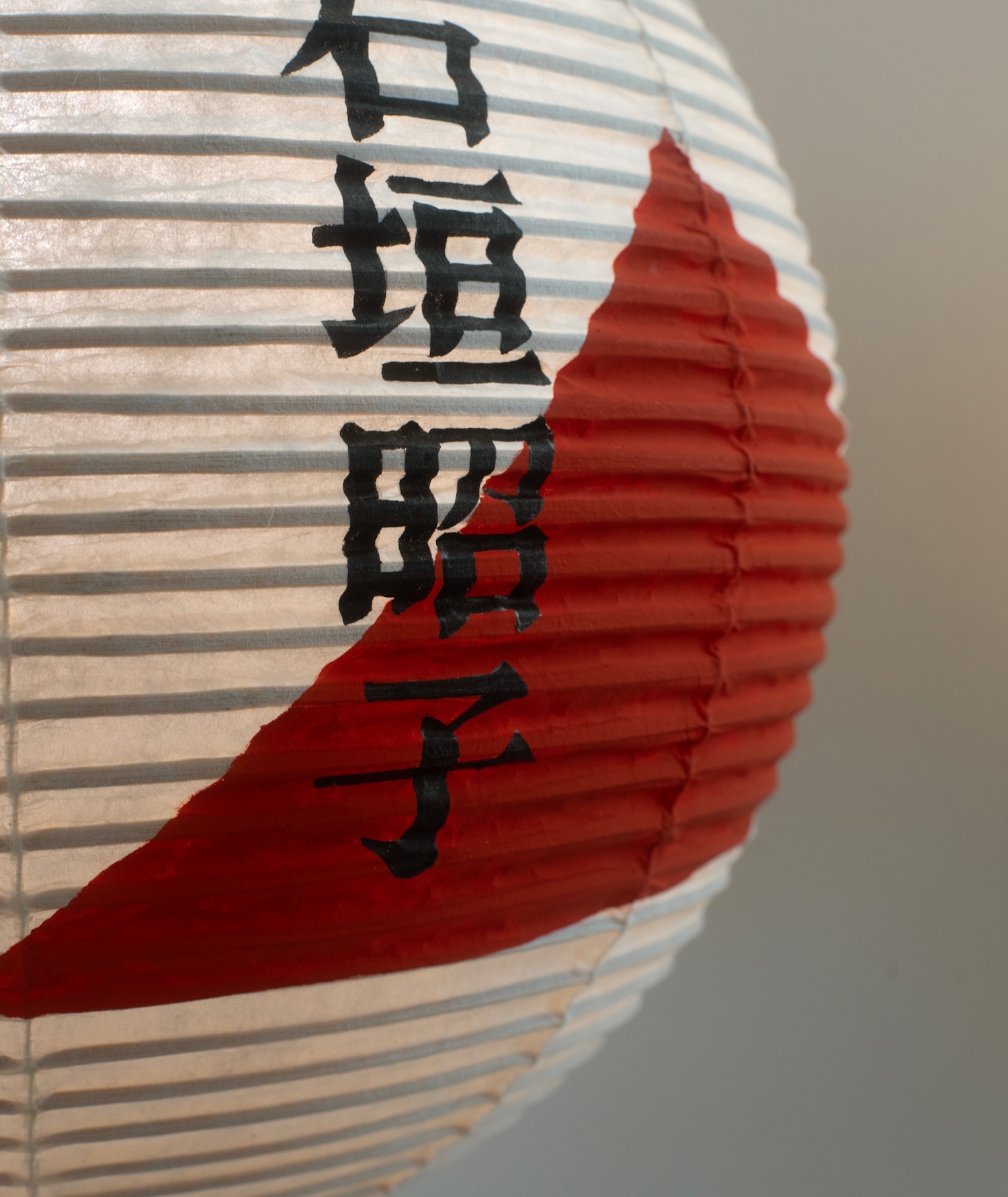

What first drew you to the American flag as a subject, not just symbolically, but as a physical object to deconstruct?

I grew up with a blaring image of the flag stretched across my grandfather’s barn, roughly half the size of a football field. It was always in my peripheral. I guess that image never left me. And I suppose now, with everything happening, I have to question what this means, or has meant, and what it actually stands for now. I think by deconstructing the flag and reducing it, I’ve been able to peel a few layers off the glimmering surface and peek my head inside.

Your materials — torch-down rubber, roofing tar, staples — are not traditionally “fine art.” What role does this industrial, utilitarian palette play in your critique or reimagining of America?

Materials have always been used to carry history. Growing up in the Midwest, there wasn’t such a luxury of “high” materials. They are more about survival. My mission with the work is to use blue-collar materials to depict images that are deeply nationalistic, religious, and drawn from popular culture. By doing so, I believe they may become more representative of the everyday person who works, who believes, who builds. In this way, I have the opportunity to bring these “low” materials to a place of excellence. I’ve always just wanted to participate, and not despite where I come from, but because of it.

Many of your flag pieces feel like they come from a job site, a highway, or a rural yard—places of wear and grit. How does geography, particularly rural or working-class America, shape your visual language?

These are my earliest references. The places I grew up in. And at one time, all that I knew. I suppose even though I have gone out into the world, there is a posture, a lens, through which I view and meet the world. My aim is to bring the job site, the open road, that backyard feeling to a place of excellence. Because it is all perfect. And I hope to shine a light on the everyday, on the sacredness of what is often overlooked.

You mention that your flags “don’t wave; they weather.” What does weathering mean to you—physically, politically, spiritually?

My flag works are worn, torn, and stitched back together. They have endured extremities over a long period of time. The works are about resilience in the face of conflict. It is the humility of decay, the beauty in something that doesn’t break. It just changes form. Even as the surface changes, what matters is what remains after belief has been tested. That, to me, is deeply American, but also deeply humanistic.

Do you see your work as a form of protest, a form of prayer, or something else entirely?

Somewhere between the two. It is mourning and a critique, but also incredibly hopeful. I am on an eternal quest for transformation, to bring all things to the good. And I am not trying to shout over the noise. I am trying to hold a mirror to what is underneath it.

Learn more about Levi De Jong at levidejong.com.

interview. Kelsey Barnes