Thu Pham Buser has never seen food as just food. For her, the banquet – or ăn cỗ – is a celebration, a place where music, abundance and memory collide. Raised in her mother’s restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City, she learned early that cooking was never just about feeding; it was about artistry and moments that linger long after plates were cleared.

Thu Pham Buser has never seen food as just food. For her, the banquet – or ăn cỗ – is a celebration, a place where music, abundance and memory collide. Raised in her mother’s restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City, she learned early that cooking was never just about feeding; it was about artistry and moments that linger long after plates were cleared.

Now based in New York City, Buser has reimagined that spirit through Ăn Cỗ, her sold-out banquet series that transforms lesser-known regional Vietnamese cuisine into immersive storytelling experiences. Each edition is a sensory snapshot of a place, memory or cultural rhythm. The latest, Island Sunsets, was inspired by years of travelling Vietnam’s coastline with her partner Taylor, capturing everything from dockside smoke and briny swims to jackfruit ice cream at dusk.

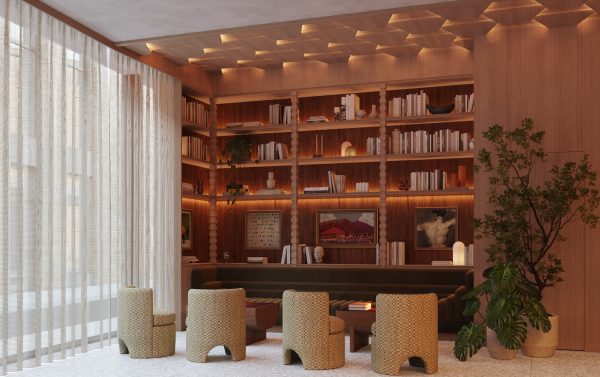

For Buser, the kitchen is only the starting point. Both she and Taylor orchestrate evenings where design, ritual and performance merge with food, pulling guests into a world both Vietnamese and New York.

We chatted with the chef about the legacy of her mother’s banquets, the freedom of cooking Vietnamese food in New York and why every plate is a story waiting to unfold.

Ăn Cỗ means banquet, which is a communal, celebratory experience. Why was it important for you to revive and reimagine this tradition in New York, and what does banquet culture mean to you personally?

Viet people are heads-down, no-nonsense types, but we take our banquets seriously. For us, the banquet is the moment to ditch the grind and turn life into a full-throttle party. As an agricultural society, banquets are also how we divide the year and celebrate our harvest.

My earliest memories are of my mom working in her restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City. I woke up to her knife on the chopping board and fell asleep to her washing dishes. She didn’t even like running a restaurant, but she still carved flowers into carrots and hand-knit napkin patterns.

My earliest memories are of my mom working in her restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City. I woke up to her knife on the chopping board and fell asleep to her washing dishes. She didn’t even like running a restaurant, but she still carved flowers into carrots and hand-knit napkin patterns.

But banquets were where I saw my mom light up. My house erupted with scallions, overflowing bowls, boiling pots and loud music as they prepared to feed hundreds. She pulled out elaborate dishes that relatives had anticipated for months.

Today, Viet cuisine has a great representation of comfort and street food, but I’ve always waited to see the splendour I remember. New York feels like it was ready-made to redesign Viet cuisine. We don’t have access to all the ingredients we have in Vietnam, but we do have a dedicated pop-up audience that loves and values food. I can’t think of another city where this would be possible.

You grew up in your mother’s restaurant in Saigon, watching her run everything on her own. How has that experience shaped your relationship to food and the way you host people now with an Ăn Cỗ?

My mom is an excellent cook, an even better teacher. As a kid, I grew to appreciate her attention to detail and her ability to do every single thing with all her heart. I hope people see that level of abundance and love in every dish at Ăn Cỗ. This philosophy is stolen from my mom. One dish I always come back to is her grilled goat. My mom got great cuts of meat and hand-marinated them in condensed milk, strong rice alcohol, and fermented tofu.

Diners can find a lot of the recontextualised hits from my mom’s menu, and I hope one day she can come to New York City and experience it herself.

The Island Sunsets menu was inspired by years of travel across Vietnam’s islands. Was there a single dish, ingredient or memory from those trips that left the deepest mark on you and found its way into this menu?

When we decide to do a region, we don’t start with the facts; we start from our personal memories of a place. We call it “chasing the high”. For example, in the recent Island Sunsets menu, we remembered the briny taste from swimming in the ocean, the smoke lingering in the air from the dockside BBQ. I wanted to make a salad that felt like my first experience snorkelling when we went to Nam Du archipelago together.

I wanted to capture the moment that Taylor and I sat eating jackfruit ice cream on our first trip together to the islands. I built a dessert that started from the fragile jackfruit ice cream notes, built up through a salty coconut cream base and flavourful sliced fruit, and then ended with eating the “sun” itself in an aromatic cherry picked at the height of summer.

We designed this series as a story of Vietnam through ten visions, so we are storytellers at heart first and foremost, and maybe educators too. I am a chef, but I am also a culinary artist, a food stylist, an OCD freak who loves food, and so much more. Taylor is a public speaker, a host and a producer, and together we love to tell stories through Vietnamese food, no matter what role we need to play.

You and Taylor not only share a life, but also this creative project. How do your roles complement each other in bringing Ăn Cỗ to life, and what have you learned about working together in this context?

You and Taylor not only share a life, but also this creative project. How do your roles complement each other in bringing Ăn Cỗ to life, and what have you learned about working together in this context?

Honestly, we’re kind of like a physical representation of the âm dương (yin yang) philosophy in Vietnam. At a high level, I do the food and the aesthetics, and he does the rest.

I feel most at home as a creator, heads down, doing my thing in the kitchen or building my tablescapes. I need him to hype up the dishes as the MC because he sees our food from the perspective of a well-informed foreigner who can also speak flawless Vietnamese.

For the coastal Vietnam volume, he asked if I would do some tablescape with coral, but I wanted a live aquarium with real fish swimming around that also doubled as a flower vase. To his credit, he actually grew four self-sustained fish tanks from scratch. On the day of the event, we know exactly how each dish is going to be served, cleared, and how long it will take to do so.

Hosting these banquets in New York means bringing Vietnamese regional cuisine into a completely different cultural environment. How do you balance honouring tradition with adapting to a city like New York?

Hosting these banquets in New York means bringing Vietnamese regional cuisine into a completely different cultural environment. How do you balance honouring tradition with adapting to a city like New York?

I’ve never felt like I had to compromise. I want to give people a truly unapologetically Viet experience. You’re going to make your own wraps by hand, you’re going to learn how to cheers in Vietnamese, how a Viet banquet is structured and try things that might challenge your palette, such as goat, frog, or fermented fish paste.

At the same time, I want to lean into the best aspects of New York City: elevated design, tasteful details, multicultural setting and feeling like we are truly on the world’s stage. In the end, we can build an environment that my grandma would recognise as a Viet banquet; the music is Viet, the tables feel Viet, my husband wears his traditional áo dài, the food looks Viet, and yet it feels right at home in the heart of the most incredible city on Earth.

You’ve said you “love to cook and feed hungry, curious people”. What kind of curiosity do you hope diners bring with them to the table at Ăn Cỗ?

No matter who comes to Ăn Cỗ, they’re going to have something new, so I always tell people to come hungry, come curious. But even for the Viet experts, we never promise to make anything “authentic”. Viet people have always innovated our dishes, crafting them from scratch or giving a twist on a foreign influence. My grilled fish with crunchy green sticky rice and Viet coriander-infused oil is a completely new dish to Viet cuisine, but one look or one bite and you know it is built on the deep principles.

Our cuisine is not frozen in time but has always been a melting pot for new ideas, fusions and flavours.

The experience of Ăn Cỗ goes beyond food. It’s about atmosphere and storytelling as well. If there’s one feeling you hope people walk away with at the end of the banquet, what would it be?

The experience of Ăn Cỗ goes beyond food. It’s about atmosphere and storytelling as well. If there’s one feeling you hope people walk away with at the end of the banquet, what would it be?

Vietnam has more than 50 ethnic groups today, over 2,000 miles of coastline – NYC to Cartagena – three completely different regions, we have mountains with snow, deserts, tropical rainforests, dense cities, ancient villages, and so, so, so much to see and eat.

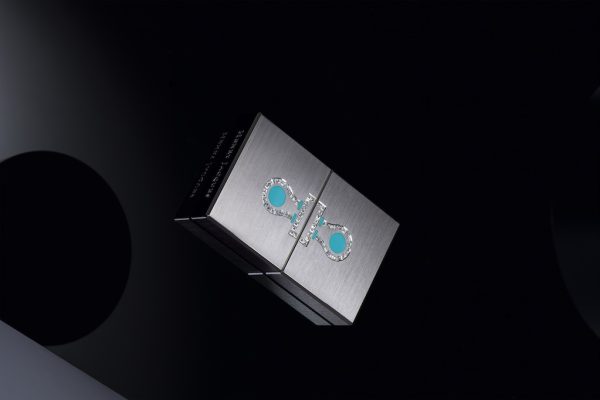

If there is one emotion I want people to leave my event with, it is wonder. I want to dazzle people with fun dessert boards, smoking jewel boxes of quail, grilled shrimp served sizzling on hot massage stones, and to see the abundant flavour and colour that Viets think of when we imagine our cuisine. I hope people go home and research about Vietnam or try a new Viet restaurant, maybe even book a trip to the country or make a new Viet friend.

I hope that this helps paint a picture that we are just scratching the surface of a profound well of taste, colour and culture and that the best part is still yet to come.

Read more about Ăn Cỗ here.

Read more about Ăn Cỗ here.

words. Naureen Nashid

photography. Wayne Francis