grandparent’s wedding (on my mother’s side)

Silver City, New Mexico circa 1914

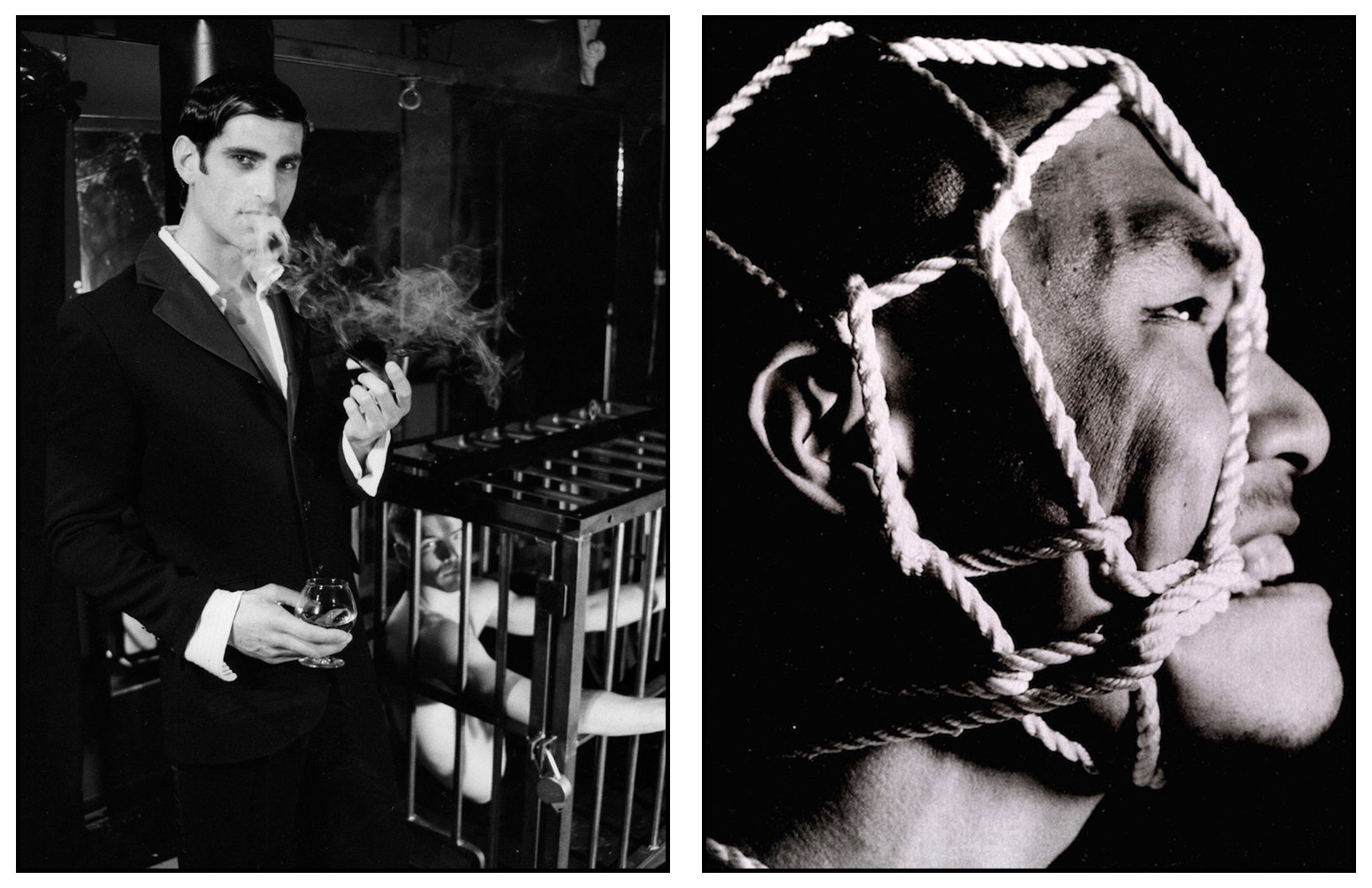

opposite

portrait of Al Castro 2014

clothing. Rick Owens

Rick Castro is a photographer, filmmaker, art curator and blogger living in Los Angeles. He is best known for his stunning black-and-white fetish photography; his Antebellum Gallery in Hollywood, featuring other fetish artists; and his jointly produced film Hustler White, a romantic comedy about male hustlers on Santa Monica Boulevard. Castro has worked with celebrities and street people, major publications and indie zines. This interview will focus on his development as an artist in a hetero-dominated world.

Thank you, Rick, for agreeing to be interviewed for Schön! Magazine. Because readers are always curious about beginnings, let’s start with some background. What is your cultural heritage?

I’ve been able to trace my maternal ancestry back to the town of Zacatecas in the state of Zacatecas, north-central Mexico. (“Zacatecas” means “where there is abundant grass.”) From what I could gather from all the questions I asked my relatives, our family is Chichimeca, originally an indigenous nomadic people who were largely decimated by Spanish colonists. My mother’s family ranch, a minimal but functional adobe structure, dates back to the 1830s. A working ranch to this day, there my relatives grow corn, garlic and chili but no longer raise livestock.

My favourite story from this branch of my family takes place during the Mexican Revolution in the early twentieth century. My great-grandfather, Crescensio Medrano, got word that Pancho Villa’s army was imminent. Toma de Zacatecas (The Taking of Zacatecas) was the bloodiest battle in the campaign to overthrow the Mexican president. On June 23, 1914, Pancho Villa‘s División del Norte (Division of the North) decisively defeated the federal troops defending the town. The revolutionary commander ordered his men to burn the crops, kill the livestock and impregnate the women. But my great-grandfather gathered all the women at the ranch — with all the silver and gold they could carry — and placed them on a train to Silver City, New Mexico.

When the war was over, he brought all the women back to Zacatecas — except for his daughter, Guadalupe Medrano, who had met my grandfather, José Maria Villagrana, and fallen in love. (Coincidentally, my grandfather was also from Zacatecas, but he had moved to Silver City when he was two. As a boy he earned income as an interpreter between silver miners and mine owners.) Once married, my maternal grandparents followed the mine workers with my grandfather as an interpreter — at this time Mexicans, Chinese and Native Americans were not allowed underground for fear they would steal the precious metals — through New Mexico and Arizona, eventually settling in Boyle Heights, California.

I know less about my father’s, Al Castro’s, side, but I do know his father was also from the state of Zacatecas. His mother, Maria Ariando, a bootlegger and a flapper in Colton, California, died when he was ten. His dad, José Castro, whom he met only once, was something of a scoundrel. There are many stories about my grandparents on my dad’s side, but they would require another interview.

I never knew any of them. They were gone long before I was even a concept.

Where were you born and raised?

Monterey Park, California.

How would you describe your childhood?

It was middle-class; mundane; little boxes made of ticky tacky, all looking the same. Suburbia at its most banal. My sister married when I was five, and my brother and I never got along, so I was always alone — or felt like I was alone. I escaped into myself on a regular basis through daydreaming, playacting and watching movies on TV. My obsessions were black-and-white monster flicks, classic 1930s Universal productions (Frankenstein, The Bride, Dracula) and all the 1950s atomic monsters. I found the drama very alluring, then would have nightmares about what I’d watched. I was also drawn to film noir — Mildred Pierce and the like. All in all, I found black-and-white imagery beautiful to watch. The darkness and the tone were romantic and soothing. And I thought my mother looked just like Joan Crawford.

What was particularly significant in your early education?

I attended Grandview Elementary school from kindergarten to sixth grade. The name was changed to Jack M. Macy Elementary after the principal, who died of cancer.

He was a lump of a man whom I had the displeasure of meeting a few times. I was sent to his office to be reprimanded. He had an actual paddle hanging next to his desk and would warn me, “This is gonna hurt me more than it hurts you.” I was dumbfounded when he took his best spank and it was nothing more than a mild tap.

Extremely shy and withdrawn, I was afraid to speak to teachers and other students. My kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Hester, told my mom that I talked like a baby but that she was mesmerised by my drawings. She couldn’t believe someone so young could draw with such clarity and detail.

I remember walking to school one morning with my neighbor — who was talking about who knows what — when my eyes fixated on a white picket fence. The fence was made of metal. My mind drifted to a castle scenario wherein I was the master. Within the chambers of my castle, there were numerous men shackled in various positions. I was about seven. I have no idea where these images came from.

My Roman Catholic parents made me attend Sunday School, aka Catechism. The structure and demeanor of the curriculum didn’t sit right with me. The nun was telling us how everything is and assumed we would believe without explanation — at least satisfactory to my mind. I raised my hand and asked, “Why would anybody die for somebody else’s sins?” This seemed to me an obvious and innocent question, but the “nunny” placed me in the back of the room with my face to the corner like a dunce.

At that exact moment, the head priest was walking by and saw my shaming. “I will take care of this,” the “priestie” announced to the nunny and the class in general. “Come with me, young man,” he commanded, and walked me into his office. Once there, he called my home and spoke to my parents. I assumed my mother would come and was very surprised when my father showed up instead.

“Wow — I’m really gonna be in trouble,” I thought to myself.

The priest said to my father, “Your son has been continuously disrupting the class.to the point where the nun was obligated to place him in the back of the room so he wouldn’t harass the other students. Even then, your son continued to be a disruption, forcing Sister [whatever her name was] to further attend to him.”

I immediately blurted out, “That’s a lie!”

The priest glared at me with all the fire and brimstone he could muster. He turned to my father. “You see what we’re dealing with?”

To my astonishment, my father responded with anger. “Why would you treat a child like this?”

The priest now turned his wrath on my father. “Well, no wonder he’s this way. I don’t think Catechism is the right curriculum for your son.”

My father replied, “Definitely not — with people like you running the place.” We left the office and drove home in silence. I never went to Sunday School again, and, soon after, our family stopped attending church. That was the first and last time my father ever stood up for me.

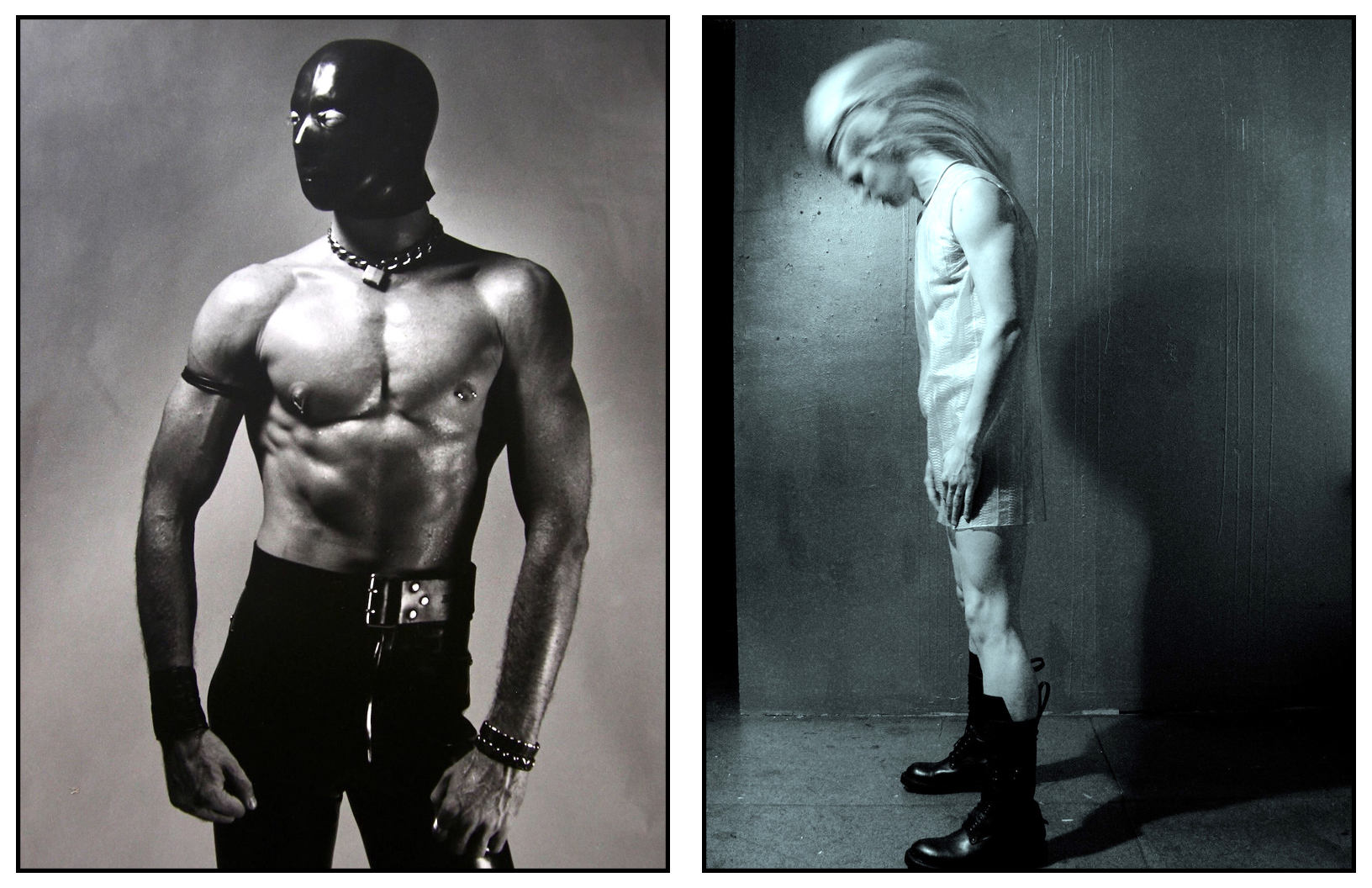

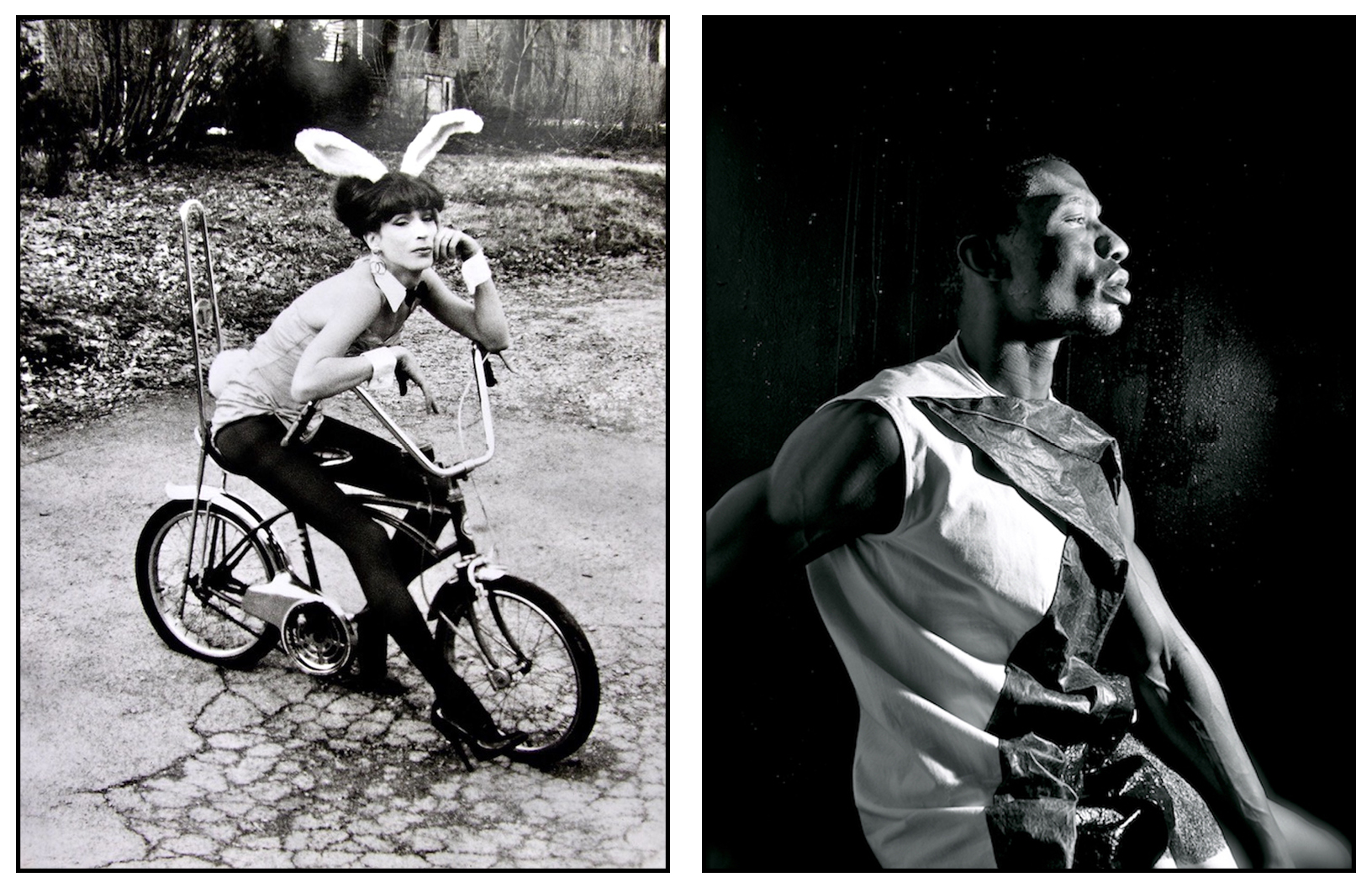

Bunny on Banana Seat Bike 1989

clothing. Playboy

earrings. Chanel

opposite

portrait of De’ Ephrim Manuel 2015

clothing. Rick Owens

What other media did you favour as a youngster?

I was obsessed with the TV series The Wild Wild West (1965-1969). Macho hero James West (played by Robert Conrad) was forever finding himself in a predicament involving bondage! Though in skin-tight Western garb, somehow he always managed to lose his shirt. (As an adult, I feel certain that a bondage fetish was in play.)

As for printed material — my mother worked at her sister’s bookstore Monday through Friday, and after school I would go with her to work. I spent every afternoon at my Auntie Nicky’s shop in El Monte, called the El Monte Bookstore. It was located downtown in the first “mall” in California — complete with angled parking and cement islands. The entrance sign, which looked like a Telletubby bubble, read “The Mall.”

Auntie Nicky’s bookstore was my entryway into the world at large, into culture and ideas. She had every issue of every Vogue, Life, Show, Look, National Geographic, Mad, Vanity Fair and Time magazine. She also had an amazing collection of what she called “girly” magazines behind the counter in individual brown paper bags. Within this collection of nudist periodicals, including Playboy and Oui, she also had Tomorrow’s Man, Bodybuilder and Athletic Model Guild. To the novice, the subject matter came off as sports-minded, but the intended audience was clearly gay.

Around this time I discovered the book A Clockwork Orange, by Anthony Burgess. Everything about this book fascinated me: the neon orange cover, the slang language, the glossary and the premise of a future dystopian world consisting of gated communities to keep out the plebeians — a world where violence was random and sexualised as entertainment. Instinctively, I knew I would not be living in a gated community. As scary as this world seemed, it rang true to me; this was the future. (What’s most alarming now is that the twenty-first century has in many ways surpassed the apocalyptic violence Burgess envisioned.)

The teen years are typically a time of self-discovery, sexual and otherwise. What did you discover about yourself and others once you were past puberty?

I was a curious young man and would go to great lengths to explore whatever I fixated on. I had a strong sense of who I was and longed for freedom, which didn’t feel possible as a teen living at home. My family pretty much ignored me. When and if any attention was paid to me, it was disapproval.

Freud describes fetishism as a mental process whereby an object of fear and horror is transformed into an object of desire — that is, into something both reassuring and (excitingly) scary. Contemporary theorists think the process is more complicated, but the classic definition works on many levels. Fetishism can be individual and/or socially shared (consider the current American obsession with zombies, werewolves and vampires). But I know your interpretation of fetishism is much more inclusive.

Freud gets too much credit.

For me, a fetish is a personalised fixation on something that defines who you are on the most visceral level. There are as many fetishes as there are snowflakes. Some are more popular than others. Some, like BDSM and foot fetishism, entered the mainstream long ago. As proof, I give you the mundane Fifty Shades of Grey series and any film by Quentin Tarantino — but especially Kill Bill and Once upon a Time in Hollywood.

As a young adult, you worked as a wardrobe stylist and costume designer with well-known artists such as Bette Midler, David Bowie, Tina Turner, Herb Ritts and Annie Leibovitz. How did you prepare for that work? How did your clothing line, I Love Ricky, come about?

I ditched my last month of high school to work at a clothing sales job in Century City. Once I had independent income, I plotted to move to Hollywood. My father had given me a 1967 Mercury Cougar when I got my license. All that were needed were a roommate and enough money for the first and last month’s rent. (My share of the rent was to be $50, and I was making $1.05 an hour.) My plan was to move on my eighteenth birthday, which I did — amid much family drama.

Although Monterey Park is only seventeen minutes (without traffic) from Hollywood, lifestyle and culture-wise, it felt like the other side of the world. Once I moved to Hollywood, things happened to me quickly, though they seemed to take an eternity at the time. (I think time moves slowly when you’re young and quickens to lightning pace when you’re older.)

I was working men’s clothing sales during the day; taking fashion illustration night classes at Art Center, Pasadena; and learning pattern-making at LA Trade Tech. Within a year, I was fired from Judy’s Gear for Guys, then worked at a designer jeans shop in Westwood. Once again I was fired, as the manager accused me of being a drug addict. “I don’t take any drugs,” I protested.

“Well, you act like you do,” the manager countered.

I then worked the graveyard shift (8 p.m. to 4 a.m.) as a paste-up artist at the California Apparel News. A new designer, Marlene Stewart (who went on to costume-design the films of Oliver Stone), brought in her collection of paper jumpsuits to be photographed for the newspaper. She liked what I was wearing and asked me if I would style the photo session. I didn’t know what a stylist was, so she said to me, “Just dress the models the way you dress yourself.”

“Oh! I can do that,” I thought, and I did. My friend Roy Johns turned out to be one of the models. A couple years later, Roy asked me to design costumes for a dance troupe he was part of at the Playboy Club, Century City. Opening night was a disaster, but the following weekend it all came together. Choreographer Toni Basil saw the show, came backstage and hired me on the spot to design costumes for her stage show, “Follies Bizarre.” About a week later, we got a call from Bette Midler. She had seen Toni’s show (Toni was her choreographer) and wanted to hire us to design for her world tour. I was nineteen years old.

From then on, I worked every day as a costume designer. My business partner, Michi — like Cher, she goes by only her first name — and I designed and made by hand a collection of hats. She thought of the label I Love Ricky, punning on the adored 1950s TV series I Love Lucy.

The following year we designed a line of clothing created from found 1960s fabrics and black vinyl. Poison Ivy of The Cramps wore our outfits onstage. Around this time I was hanging out at a supper club on Beverly Boulevard called the China Club. I had a buxom punk girlfriend whom all the hets swooned over. This corporate-type guy took me aside and said, “Please, would you hook me up with your friend?” I did, and they ended up having a fling. He was so appreciative that, on their way out of the club, he said, “Here’s my card. Call me, and I’ll hook you up!” I called a few days later, surprised that he remembered my name. The next day I’m in his penthouse office back in Century City, showing him my portfolio. He says, “I’m going to connect you with an agent.”

A week later I’m in the office of an agency, and the secretary, Chantal Cloutier, looks at my portfolio with amazement. She says, “I’m thinking of buying this agency. Do you think I should?”

“Sure,” I say. I brought her Italian fashion magazines, Per Lui and Lei, as visual samples of the type of magazine I wanted to work for.

The following week, Chantal called me and said, “I got a call from a photographer who’s shooting for Per Lui and Lei. Since you’re familiar with these magazines, you’re the perfect person to style the shoots. The photographer is a new guy named Herb Ritts.”

I worked for Herb Ritts, George Hurrell, Joel-Peter Witkin, and numerous photographers, celebrities, magazines, MTV videos and commercial productions for the rest of the eighties. During this time I injected fetish into everything I did — from something as simple as black jeans and engineer boots (surprisingly daring in 1980) to a custom-made fetish leather corset for Tina Turner to full-on leather and rubber on model Veronica Webb. This put me at odds with editors who, surprisingly, were not as adventurous as one might think. I remember an altercation whereby I was told that styling an unknown actor for Interview Magazine in clothing by an unknown designer working with knitwear and rubber was just “too much.” The unknown designer was Gianni Versace, and the unknown actor was Rob Lowe. My styling career continued through the mid 1990s until I teamed up with filmmaker Bruce LaBruce, who asked to collaborate by turning my male hustler photo-shoot stories into a feature film.

After this, I left styling for good and was happy to end this chapter of my life. However, I did style the wardrobe for our film, Hustler White (1996).

BDSM culture can be seen as socially shared fetishism, as the images of police, militia and executioners certainly represent groups historically dangerous for those who are culturally “othered.” When did you find yourself drawn to this imagery, including the leather, straps, chains, grommets, cop caps and boots?

For me, it was organic. But I wasn’t drawn to the imagery of authority figures. I was drawn to the romanticised, highly sexualised imagery of Marlon Brando in The Wild Ones (1953); to Tom of Finland; and to early Drummer magazines. When you watch The Wild Ones with a twenty-first-century point of view, you can see it’s clearly homoerotic — with men dancing together and slapping each other’s bums.

And the first “biker gang,” the Stayrs (founded in 1954), was all gay men. (They are still around, by the way, with younger members joining.)

In 1978, I went to my first leather bar, Griff’s on Melrose Avenue, wearing a red Fiorucci shirt and red Annie Hall glasses. I was the youngest and thinnest guy there by twenty years and sixty pounds. Nobody spoke to me.

At the time, I was working at the California Surplus Mart on Santa Monica and Vine. During lunch (happy hour), my much older coworker, Jim, and I would walk across the street to the gay uniform bar called The Academy. Here was a saloon full of men in full uniform, cops, cadets, soldiers — in full-fledged macho gear — debating show tunes. I learned quickly that image and mindset can be very different things.

As you moved into fetish photography in the 1980s, whose work influenced yours?

Castro: The historic figures (not only photographers) who inspired me — and continue to inspire me — are Pierre Molinier, Brassaï (Gyula Halász), Pier Paolo Pasolini, Roman Polanski, Tennessee Williams, J. K. Huysmans and Gilles De Rais.

Where was your studio located? How did you find models?

I was living in the Brewery Building (now one of the most established, overpriced artist residences in L.A.) on the outskirts of downtown Los Angeles — in a 2500-square-foot, 30-foot-ceiling loft with a roomie. My share of the rent was $400.

I took my first two professional photos during the spring of 1986 with a basic Instamatic camera. The first was of a former roomie, Odessa Sterling, wearing a Morticia Addams costume of my design. Very stark, black and white. The following week I shot an unknown model I’d discovered while grazing through a Blueboy magazine — Anthony Borden Ward. I’d lusted after his centerfold for months.

While I was styling a men’s fashion magazine, the photographer had asked for help with casting. I called the phone number at the bottom of the page of Anthony’s centerfold, which read “Anthony Borden Ward — Management: Blue Leader.” When “Blue Leader” answered the phone, I put on my best professional voice, describing my work, the magazine and the photographer. He interrupted me midway and said, “If you can pay for his bus fare, you got him.” During our fashion photo shoot, I took Tony aside and asked him if he’d model some leather gear a designer had recently created.

These first two photos really pleased me. They were stark and contrasty, with deep black tones. (The photographic term is “snappy.” I like my images to be snappy.)

I decided to invest in a better camera. While working as an art director, stylist and assistant to Joel-Peter Witkin in Albuquerque, New Mexico, I asked him if he would help me select a camera. Witkin took me to his local camera shop (there was only one) and chose a Nikon FG. It was perfect for me: basic, straightforward, no frills.

For the remainder of that year and into 1987, I shot everything and everyone. I had a new camera eye. (When you begin work as a new photographer, you are now looking at the whole world through a camera lens. You are seeing everything for the first time — it’s all new.) My photographic memory and intense awareness of detail now had a means of expression. And a camera in front of your face is the perfect hiding spot. Plus, people will do things for you when you have a camera.

Having worked as a wardrobe stylist for fifteen years with photographers who became legends, I knew their strengths and focused on images I knew I could recreate. From George Hurrell I had learned tungsten lighting and posing models. From Herb Ritts I had learned ambient lighting as I literally followed him, chasing “the golden hour.” (This is sunrise, 7:00 a.m. till 10:00 a.m., and sunset, 4:00 p.m. till 6:00 p.m. When the sun is on the side, it’s the most flattering lighting ever.) From Joel-Peter Witkin, I had learned how to create allegories with a nod to the classics.

Where was your first solo gallery show?

My first two exhibitions were at the original Different Light Bookshop in Silver Lake, a Los Angeles neighborhood: “Nothing But a Man: Everything But a Woman” in 1987, followed by “Mass Murder & a Cute Boy” in 1988.

During this time I was frequenting the One Way on Hoover Avenue in Silver Lake — in my opinion the best leather dive bar in L. A. The drinks were cheap, and the guys were hot and lusty. You were always guaranteed a “date” at the One Way.

There was a leatherman whom I approached. We made out for a bit, then decided we were two tops, so there was no “love connection.” Still, he gave me his phone number on the bar’s matches (this was the pre-cell-phone era).

When it came time for my opening-night exhibition, that same leatherman pulled up on his Harley, checked out the exhibition, then approached me and said, “I’d like to buy some of your photographs. Would you like to publish a book?” He turned out to be Durk Dehner, president of the newly formed Tom of Finland Foundation. He was my first collector and publisher.

Which magazines published your work?

In the early days (1986-87), I didn’t think about having my work published. I was still exploring and not sure that I wanted public exposure. During the eighties, it was a huge commitment to present the type of imagery I was creating. I knew that, once I committed, I would have to own it and stand by it.

After Durk Dehner offered to publish my book, the time felt right, so I sent an envelope of prints to Drummer Magazine in San Francisco — the granddaddy of all leather publications. (Robert Mapplethorpe had his first cover published by Drummer.) At the time I was living in New York City, working as a wardrobe stylist. A friend was serving as an assistant to Annie Flanders, editor of the newly published Details magazine. (In the beginning, Details was an art/underground publication — not the slick, glossy men’s magazine it has become.) So my friend made an appointment for me to show Annie Flanders my portfolio. She rummaged through it quickly, then turned to her assistant and said, “Must I be subjected to this?” Then I got a return letter from Drummer, saying, “Thank you for your submissions. Although they are hot, they’re out of focus and too artsy for us.” I was too kinky for fashion and too artsy for kink! But this was who I was: a combination of both.

About three years later I received a letter from the new editor of Drummer magazine, Joseph W. Bean, asking if I would submit photography. Since I had been flatly turned down a few years prior, I questioned Bean about the magazine’s change of heart, to which he replied, “I am the new editor at Drummer. It would be my honor to publish any images you would be gracious enough to share with us.”

Much later, around 2000, I received an email from Long Nguyen, editor of Flaunt, a high-end fashion magazine based in L.A. and New York, asking if I would like to shoot an editorial for the latest Dior Homme collection, by designer Hedi Slimane. Given my experience with Annie Flanders at Details, I asked if Nguyen had actually seen my work, to which he responded, “Yes, which is the reason I’m asking you to shoot for us.”

It took five years for my art to be accepted in a kink magazine and fourteen years for my kink to be accepted and embraced by art and fashion.

Who published your first book? What other kinds of publication did you pursue, having made a commitment to fetish art?

Castro (1990) was published by Durk Dehner from the Tom of Finland Foundation under the moniker DPR (Dehner Public Relations) Press.

In 1992, I was involved in Spew: The Homographic Convergence, the second queer zine convention, held at LACE, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions. I debuted my Xeroxed zine, Zack, featuring photos and an interview with a street hustler I had met on Santa Monica Boulevard. I was also the photo editor of the now legendary Fertile La Toyah Jackson Magazine, created by Vaginal Davis. I shot all the covers and editorials under the alias Beulah Love.

From then, I self-published The Bondage Book (#1 in 1993, #2 in 1994, #3 in 1995 and #4 in 1996), a Xeroxed zine featuring my photography and that of other artists who would otherwise have little chance of publication. I sold my zines through mail order and bookshops such as the Different Light bookstores in Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York City and Quimby’s in Chicago. Even Tower Records in New York carried my Bondage Book. Zines were a very popular component of queer culture in the early 90s. Pre-Internet, they were the vehicle outsiders used to meet one another. I eventually turned the Bondage Book and Fertile LaToyah Jackson zines into one-hour-long videos.

Tell us about the film accepted at Sundance. When you collaborated with Bruce LaBruce, how did you arrive at the title Hustler White? Did the film receive international attention?

Through zines I met Bruce LaBruce, who came to Los Angeles to attend Spew. We spent a lot of time together, going to films and clubbing. He was working on his next film, Super 8 1/2, and asked me to shoot a scene of him with drag diva Vaginal Davis dressed as a prison matron (styled by me). This was the first film footage I ever shot. During this time I showed Bruce VHS footage of a documentary I was working on, about hustlers on Santa Monica Boulevard.

The footage consisted of interviews I had conducted with male hustlers off the street. The title of my project was Hustler White, a term I originated, as boys on the boulevard preferred white jeans for easy visibility via car headlights. (White also made their baskets look bigger.)

Bruce suggested we collaborate as co-writers/directors to make a feature-length film. I cast in various roles the boys I’d been photographing and invited my longtime model/muse Tony Ward (Anthony Borden Ward) to play the lead hustler, Montgomery Ward. I also styled all the wardrobe; acted as location scout; and shot all the still photography, including publicity and movie posters. My car was used in the film, and my apartment became the production office and set.

We shot the film in ten days during the summer of 1995, then worked for the rest of the year on post-production editing — running out of funds more than once.

The film was accepted by Sundance on the basis of a rough cut and premiered at the 1996 Sundance Film Festival at the historic Egyptian Theatre. We had a sold-out, standing-room-only crowd — yet lost half the audience during various scenes that viewers found too hard to take. But the people who mattered loved it.

I spent the remainder of 1996 through 1998 traveling the world to film festivals and presenting my photography at exhibitions. Hustler White had its theatrical debut at Laemmle’s theater on Sunset Boulevard to sold-out screenings — with a few folks fleeing the theater at every show.

Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times gave us a glowing review, as did New York Times critic Stephen Holden, and the film became a cult hit. In the November 20, 2003 issue of the Los Angeles Times, film critic Manohla Dargis included Hustler White in her list of the best underground films created in Hollywood, 1913-2003.

MTV featured one of your films, Plushies and Furries, in 2001. What was your experience in putting together that show?

I had an art booth at the first Tom of Finland art fair in 1996.

In my previous Bondage Book zines I had published many obscure artists internationally. One of these artists came to meet me at the fair. Mr. Drake drew images of Hanna-Barbera fox and wolf characters — the XXX-rated versions. He told me he was on his way to a furry convention. I assumed he meant furry like the bear community (heavy, sometimes overweight, scruffy and hairy gay men) of that era. “No,” Mr. Drake clarified, “these are people into anthropomorphic animals and role play.” I didn’t understand but asked if I could attend with my camera. On January 16, 1997, I went to ConFurence 8 at the Buena Park Hotel, California.

Having lived within transgressive cultures since the late 1970s, I considered myself a somewhat jaded person, but on that evening an entirely new world opened up to me. I proceeded to document furry culture for three years, then presented my idea and raw footage to a new production company, World of Wonder. They joined me as producers, and we sold the program to MTV.

Plushies and Furries scored number 2 in the ratings, with continuous rotation for six months during 2002. Furry culture was one of the first subcultures largely organised online, then transferred to groups meeting in real time. Since my documentary, furry has become mainstream (as eventually most fetishes do).

Ironically, many furries were angry with me for portraying the community in a sex-positive light. Some furries considered the sexual aspect a minor feature of the community. I see this as a closeted viewpoint, comparable to that of part of the gay community — a community that, for many years, was vilified and dismissed as sexual perversion — so I understand furry anger over being portrayed as sex-driven beings.

My goal was to present a new culture to the world at large, without prejudice towards its sexual behavior. But America continues to stigmatise minorities and non-heteronormative sexuality.

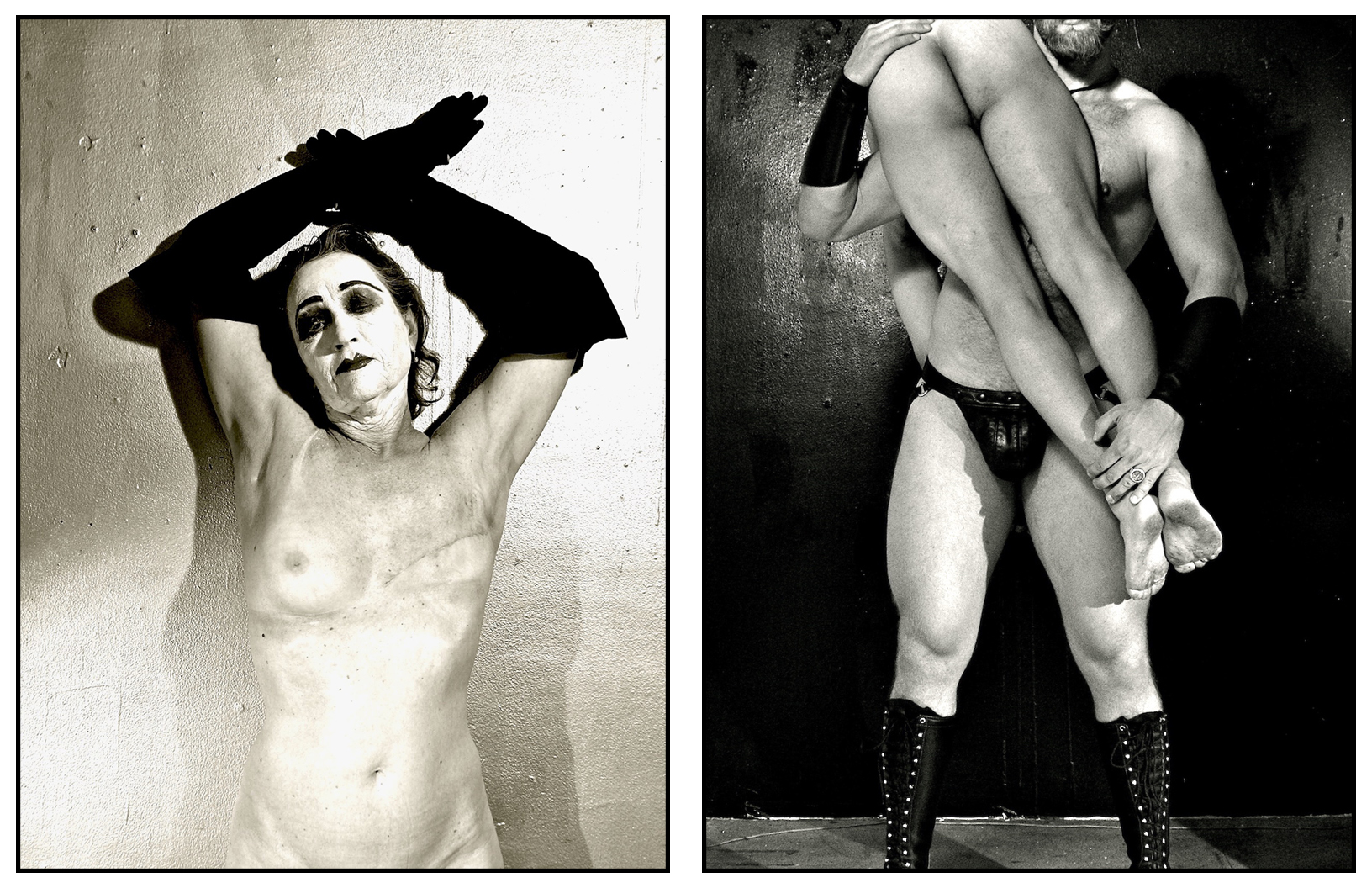

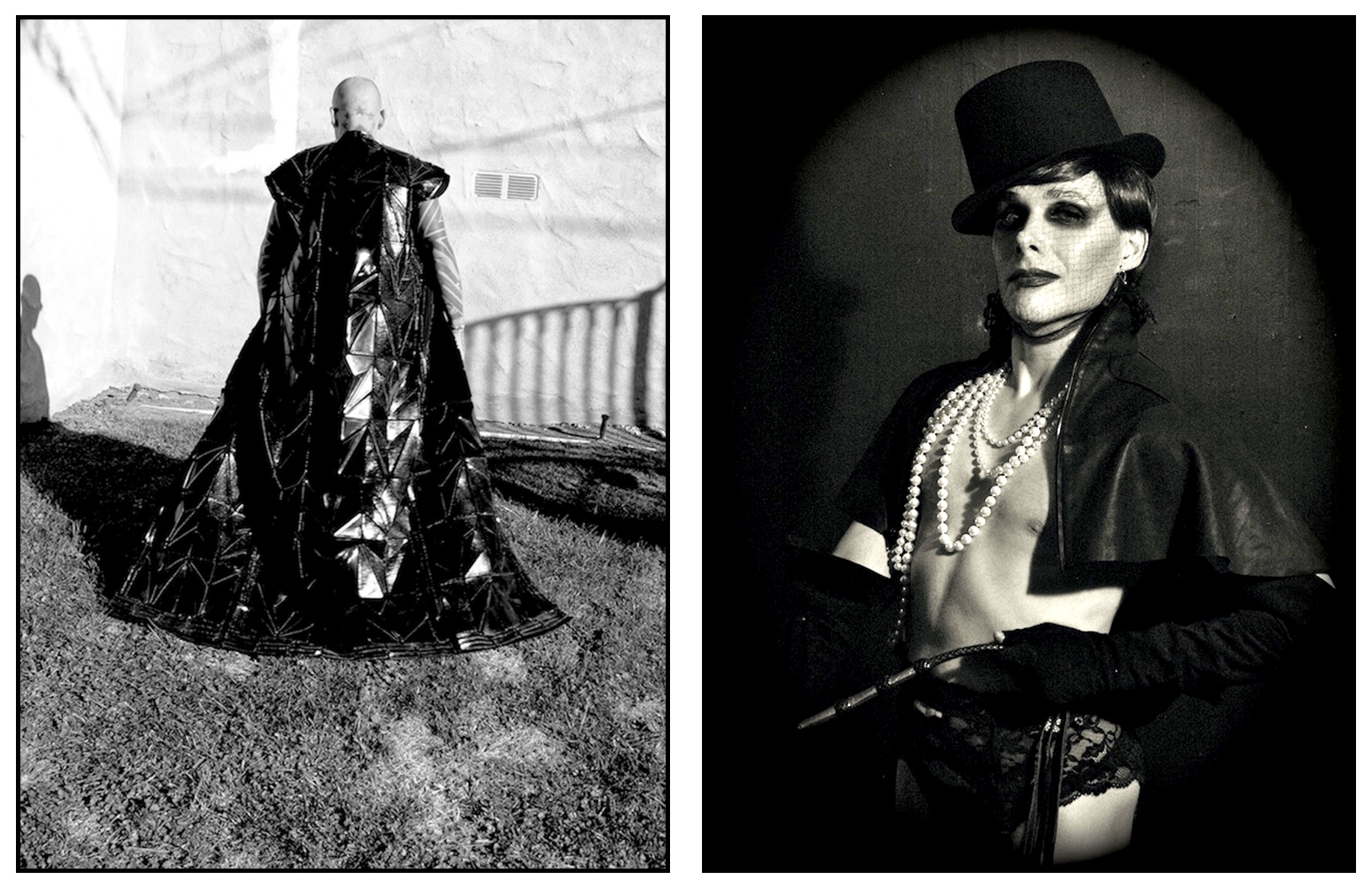

Ron Athey in his front yard 2019

clothing. Rick Owens

opposite

La Maîtresse: After Pierre Molinier 2013

clothing. Cere

Who published your second book?

13 Years of Bondage (2004) was self-published by myself and graphic artist Mark Harvey under the imprint Fluxion Editions. The plates were printed in China, with the finished book distributed by a few companies in North America and Europe. During 2006, I had a European book-signing tour through Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam and London, which included photographic exhibitions.

How did the Antebellum Gallery come about? Whose work did you feature? Who were some of your better-known customers?

My first gallery curatorial experience was in the back building of Les Deux Cafés, Hollywood, in 2002. Proprietor Michèle Lamy was a fan of my documentary Plushies and Furries and very intrigued by furry culture. I had known Lamy since 1978, when she opened her shop in West Hollywood, Too Soon to Know. I had also designed a menswear collection for her company in 1987 and 1988, called Lamy Men.

I presented my Plushie art show during the summer of 2002, to great success. Mickey Rourke purchased art, as did Tommy Perse, the owner of the legendary clothing boutique Maxfield.

Michele Lamy and Rick Owens lived across the street from Les Deux Cafes at three storefronts. I eventually opened Antebellum Gallery next to these storefronts on Las Palmas Avenue, Hollywood.

With Mark Harvey, I worked on modestly renovating the space. The first opening of Antebellum Hollywood, “Erotic Pioneers,” took place on November 11, 2005. Our grand-opening exhibit featured every name in homoerotic history and fetish, from F. Holland Day to Willem von Gloeden to Mel Roberts to Bob Mizer to Peter Berlin to Herb Ritts to Joel-Peter Witkin to George Quantaince to Tom of Finland to never-before-seen artists in their first-ever exhibition — e.g., Mr. Drake, Robert Hill and Tony Ward. And, of course, there was Rick Castro.

How did the press characterise your shows?

The gallery was an instant hit, with write-ups in L.A. Weekly and New York Magazine. Mainstream press characterised the gallery as raw, outsider, anti-censorship, erotically dangerous and “relentless,” which I loved. I had a strong, dedicated collector base, including Ken Burns, one of the original founders of the Mattachine Society, the early national gay rights organisation; Francesco de Simone, creative director for Armani; film director Clive Barker (who wrote an endorsement for 13 Years of Bondage); designer Rick Owens; Tom of Finland president Durk Dehner; architect Tim Campbell; and, later on, legendary costume designer Bob Mackie.

What activities did Antebellum sponsor? When did you change the gallery name to Bellum?

For the first year, we presented exhibitions on a bimonthly basis with the theme “fetish as art.” Within a year, Mark Harvey decided the project was too time-consuming and a personal drain, so he left the gallery to me. I think we both assumed it would close, but I persevered on my own, presenting a different fetish monthly for the next eleven years. Some of the exhibits I curated were The Bondage Show, Automolove, Modern Heretics, Fools for Feet, Clownie, Baby, Amputee, Cinch Me, The Pony Show, All Them Witches, Club F*ck! Reunion, Benefit against Proposition 8 and The Resurrection of Robert Opel: Fey Way Studios (the original inspiration for Antebellum Hollywood).

By the way, the term “antebellum” is often understood as representing the pre-Civil-War, slavery-plantation American South, but I was using the term in its classic sense. Antebellum is Latin, meaning pre-war. When I opened the gallery in 2005, a number of culture wars were in full bloom — with a public divided for and against the first black President, gay rights, minority rights and sexuality. As the Trump world came into play, we passed the antebellum era and were now entering into full bellum, or war.

Why did you close the gallery?

I was randomly attacked on the subway platform on my way to the gallery the morning of Valentine’s Day, 2016. Then Trump won the election, and I just couldn’t concentrate anymore. The area was changing — and not for the better. Everything seemed pointless, now that an actual dictator was President. I changed the focus of my gallery to political matters. (Everything can be fetishised, even politics.) My last exhibition — on December 3, 2016 — was titled “America Matters.” This was confusing to my longtime patrons, as you can imagine.

Antebellum Hollywood officially closed on January 1, 2017. All in all, a thirteen-year run for a gallery is not bad. I was one of the longest-surviving independent businesses in the historic core of Hollywood.

Name some of the periodicals that have published your work in the last two decades. Where is your work archived?

L.A. Weekly. Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Magazine, New York Magazine, Flaunt, Vice, Dazed Digital, The Advocate, Attitude (U.K.), Another Man (U.K.), Document Journal, Gayletter, Homosurrealism, Mascular Magazine, Means Happy, Kaltblut, Pineapple Zine, Glamcult, Naked But Safe, Narcissus Magazine, Chaos Reigns, The Hollywood Reporter, Metal Magazine, Crush Fanzine, My Gay Eye, WWWD, Terremoto, Autre, Culture L.A., Numéro Berlin, King Kong Garçon, PEN America, i-D Magazine. I also served as the West Coast editor for Studio Magazines (Australia) from 2001 to 2006. And in June of 2019 I was featured in the historic first queer issue of Los Angeles Magazine.

Currently I’m a regular contributor to AnOther Magazine (U.K.); Document Journal (New York City) and Homosurrealism (Atlanta).

My photography, films and books are archived at the Alfred Kinsey Institute at Indiana University, the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at USC, the Leather Archives and Museum in Chicago, the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York City, the Outfest UCLA Legacy Project Film Gallery, El Insulto: Archivo y Librería Sobre Cultura Sexual in Mexico City and the Tom of Finland Foundation in Echo Park, Los Angeles.

Over the years I have created fashion, images of architecture, animal portraits and personal portraits, so not all of my work is sexual, but I do approach my subjects with a fetishistic eye.

How did you get the title “Fetish King”? What kinds of resistance have you encountered from mainstream folks?

“Rick Castro: Fetish King — Seminal Photographs, 1986–2019” was a retrospective exhibition of my photography, focusing on the classic leather/BDSM body of my work. The exhibition was curated by Rubén Esparza and presented at the Tom of Finland Foundation on April 6, 2019. There was significant press prior to the show, and the opening event was packed with an amazing crowd of friends, collectors and fans.

One month before the event, The Advocate did a great preview story on the exhibit and posted on my Facebook page. Within hours, Facebook banned me from posting for thirty days with claims the posting went “against community standards.” I must point out that The Advocate has been around since 1969, the Tom of Finland Foundation has been around since 1984, and I have been working as a professional photographer since 1986. We are older than social media. We are the community.

I contacted The Advocate, asking them, “What’s going on?” They responded that Facebook randomly gives them problems regarding censorship. The editor suggested I write a statement about the censorship (the statement included a photo of me sitting on a bench in Chinatown, fully clothed) and they would repost. I did so, and The Advocate reposted. In response, Facebook banned me for sixty days and The Advocate for one day. Vice President of the Tom of Finland Foundation S. R. Sharp, curator Esparza, and my gallerist, Lisa Derrick, all tried to post and were banned. Lisa Derrick contacted the L.A. Weekly, who in turn sent a message to Facebook, who apologised to them (but not to me) and reinstated my account. All this took a great deal of time, so, because of the initial ban, I wasn’t able to promote my exhibition on social media.

I bring this up because, during this time, numerous LGBTQIA+ artists were targeted with bans and censorship, which has now become endemic in social media, specifically with platforms owned by Zuckerberg: Facebook and Instagram. The censorship of this content in the twenty-first century mirrors the vilification with which the government treated the gay community during the McCarthy era. Every non-heteronormative person I know has had content removed for the false reason of “going against community standards.”

The falsehood perpetrated by social media corporations is insidious and dangerous. It is a modern-day form of erasing an unwanted minority. Since the beginning of my photographic career, it’s been important for me to push back against censorship and hetero-dominated institutions. In 2021, with the normalisation of white supremacy and religious-right zealotry, it is imperative for survival. We are indeed in the midst of bellum.

When did you begin your blog?

I began June 14, 2009, and have continued to the present, trying for once a day. At this time my blog is predominately found visuals that portray my mood. Whenever I include my images, I credit and give titles. Occasionally I post one or two video clips and sometimes include my writings and/or rants.

Has your cultural background/heritage influenced your work?

As a third-generation American who grew up in middle-class, predominately Caucasian suburbs, I wasn’t much exposed to Mexican culture as a child and felt far from my roots. Suburban culture was prevalent, so I was pushing back against that.

As an adult, I’ve grown to have a deep appreciation of my origins. If there is any influence, it would be in my acknowledgment of ritual, of energy from nature and of grounding from the earth. I touched on this with my Against Nature: Outdoor Series, a group of images featuring panoramic shots of the great outdoors, with a nod to Ansel Adams. My landscapes include a bound body somewhere in the setting. Totally out of place — yet it fits perfectly.

How has your family responded to your photography?

First, you have to understand that my family didn’t accept my gayness for many years — refusing to talk about it and choosing to ignore it. That’s why the second I turned eighteen, I was outta there! I very much wanted to discover myself and to be who I was.

An amusing anecdote sums up the relationship. During the 90s, when I was living in West Hollywood, my apartment was barren, to allow for photo sessions. On display were my photography, that of Joel-Peter Witkin, Pasolini film posters and other imagery of this nature. About every three months, my mother would force my father to drive her to visit. These visits would traumatise my father. As I welcomed my parents in, my father would grimace immediately. Placing his hands to the sides of his eyes, like horse blinders, he would say, “Does it have to be all over the house? Can’t you confine it to one room?”

Having been on my own for about fifteen years, I felt this was an insulting, demeaning comment, so I retaliated: “I’m an adult in my own home. I can display anything anywhere I want. I can put an erect dick on my front door if I like.”

Meanwhile, my mother, looking at my photo of Tony Ward as a biker, said, “Doesn’t Tony have any shame? How can he expose himself like that?”

I responded, “That particular photo sells for five hundred, and I’ve sold four so far.” Then both my parents looked at the photo, and their expressions changed to interest.

Three months later, it was time for another parental visit. My father was already preparing his disapproval face as I opened the door. He saw a painting by serial killer John Wayne Gacy, Pogo the Clown, that I had hand-framed in Kelly-green wood. The painting is a poorly rendered self-portrait of Gacy as a clown holding balloons. My father was elated. “Finally, some nice, happy art!”

Above you’ve mentioned learning photographic techniques from photographers with whom you worked. Can you explain in more detail how some of these inherited strategies have informed your oeuvre?

I shoot all my indoor sessions with tungsten lighting (nod to George Hurrell), the most classic form of studio lighting — basic and to the point. Noir drama can be achieved this way. How you angle the key light (the main light on the subject) and fill lights (background illumination) makes or breaks a photo.

My choice for all location/outdoor shoots is ambient light (nod to Herb Ritts). Golden time works well for casting long shadows, very atmospheric.

I choose classic poses for models (nods to George Hurrell and Joel-Peter Witkin) that evoke the most drama. Heroic or horrific with moody, tense, sensual energy. I approach the overall composition of the photo as if it were a painting. I look to tell a story.

When I first viewed your fetish work, my initial thought was “This is ballet with full frontal nudity.” Others have described your photography as “theatrical” or “cinematic.” Art critic Edward Lucie-Smith has found echoes of religious art of the Baroque period — specifically of paintings depicting martyrdom and religious ecstasy.

For me, the image should have a timeless quality. Black and white can contribute to this. When I choose colour, I always keep black tones to hold the richness. With mood and posing, I’m looking to present open allegories — those one can go back to time after time and experience different interpretations.

Religious imagery is not my intention, but I’m creating intense sexual imagery with a classic feel, so perhaps it’s not surprising that one could interpret the images as religious. It’s my belief that fetishism preceded religion.

Have you conversed in person with any of your forebears in fetish photography?

Back in the day I met legendary artist (and photographer) Tom of Finland at the home that became the Tom of Finland Foundation. I also attended his first exhibition at Circus of Books in West Hollywood. He was tall and quiet.

Of course I had numerous conversations with Joel-Peter Witkin during the eighties. Besides helping me choose my first professional camera, he wrote the forward to my first book, Castro, where he referred to me as “a priest of love.”

In 1990, I had the pleasure of spending the afternoon at the home/compound of Bob Mizer of the legendary Athletic Model Guild, a photography and film company he established in 1945. It featured male models in various stages of undress as laws changed over time. Not only did I speak to the master in person — I was able to walk around and view his estate (now in a state of decrepitude), where he created homoerotic history. Mr. Mizer was very kind and encouraging. After thoroughly looking over Castro, he said, “I’m very happy to see the tradition will continue with you.”

I interviewed reclusive photographer David Hurles of the Old Reliable Tape and Picture Company at his palatial estate in the Hollywood Hills. (His mansion was next to that of the creators of the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers.) David confessed to me, “Your work is beautiful, but I have a bondage phobia. I was robbed during a home invasion and was left tied up for twenty-four hours.” (This example points to the difference between wanted and unwanted fetishism. If you’re into it, it can be a joy; if you’re not, it can be hell on earth.)

During the early 2000s, I spent a pleasant afternoon with another legend, George Dureau, at his atelier in the French Quarter, New Orleans. He showed me his collection of prints and confided that one of his biggest collectors was Robert Mapplethorpe. Whenever Mapplethorpe announced he was coming for a visit, Dureau would hide his newest work — because, he said, Mapplethorpe would copy it.

I had met Robert Mapplethorpe briefly, at his book signing in New York City, in 1982. When I arrived at the bookshop, B. Dalton on Eighth Avenue, I was surprised to find in attendance Mapplethorpe, Lisa Lyons (the first female bodybuilder), and me — that was it! I had the perfect opportunity to speak with him. Not only was I the only guest — he had actually photographed Lyons posed on a pony, wearing an outfit from my clothing line, I Love Ricky. At the time I was simply too shy and ended up leaving.

I exhibited with San Francisco-based photographer Charles Gatewood, who documented the underground sex-club scenes of New York City and Folsom Street, San Francisco, from the 70s through the 90s. Gatewood produced over thirty documentary videos about fetish fashion and alternative culture.

I also exhibited with legendary shaman Fakir Musafar at Antebellum. Fakir documented body modification from his teens, taking self-portraits in the mirror from 1953 until his passing in 2018. He instigated the Modern Primitive movement, whereby contemporary folks adopt the body modification practices (tattoos, piercings, brandings, scarification, etc.) of indigenous peoples.

One of your photographic series was titled Après Pierre Molinier. Who was Molinier, and how did the series pay tribute to him?

For me, Pierre Molinier is the very best example of a fetish artist. Born in 1900, he began creating photographic self-portraits at the age of eighteen in his tiny atelier in Bordeaux, France. Molinier used himself as model, wearing corsets, heels and fetish gear that he fashioned himself. Sometimes he made collages of himself — to suggest an orgy. He also invented the high-heel dildo. In 2013 I created an editorial series as homage to Molinier for a Swedish art magazine.

Do you “see” a specific image in your mind before you go about creating an image for a photograph, or is your process more spontaneous?

Much of it is spontaneous. My idea is generated by the person who will be modeling. I quickly size him up and decide how I want to present him, taking into consideration what he is personally into. I want the final image to look raw. When I shoot fashion, there is more set-up and organisation. It becomes a production: acquiring the clothing to be used, casting the models, finding the hair and/or makeup artists.

Many artists have personal rituals or protocols they enact as they get ready to work. Do you?

I arrange all sessions in my mind beforehand: organise whatever props and gear I might be using, set up my lighting and then basically fixate on the subject I’m about to shoot. For me, obsession is a driving force. I have to desire to photograph my subject. If I don’t, the result is bland. I also prefer to work without other people present. They become a distraction for me.

What projects have you taken on recently?

Thanks to a grant from the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, I’ve contributed to a project titled Reimagine Public Art: House and Home. I chose to document the aftermath of the wildfires last summer — which came within fifteen miles of my cabin retreat during the plague. Instead of my usual nude, my model wore a hazmat suit.

I completed an online memorial dedicated to one of my first models, the Goddess Bunny, with a grant provided by the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs. She was a quadriplegic transsexual woman, legendary online and in real time. She died of Covid-19 in February of 2021.

I also received a grant from the city of West Hollywood to participate in Pride Publics, a public art display for L.A. Pride month. The display opened in West Hollywood, then traveled to Los Angeles State Park and landed at the Occidental College InterCultural Center in Highland Park, California, from June through October of 2021.

My photography was featured in Queer Communion: Ron Athey at Feature, Inc. in New York City, then moved to the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, from June through September of 2021.

The virtual photo series that I began during the first plague lockdown in March of 2020 continues to occupy me. By connecting with people on social media, I’ve organised dates in accordance with time zone, then created sessions on Zoom, using screen shots. I plan to make this work a zine — in print or online.

During August of 2021, I presented a real-time exhibition titled Rick Castro: Reformation: 1st Exhibition since the Plague and participated on the organising committee for the Tom of Finland Art and Culture Festival — TOM 101 (as in years old). My exhibition Rick Castro: Torture Garden took place at that festival in East Hollywood in December of 2021.

In 2022, my short films were featured in the Film Maudit Festival at Highways, Santa Monica, during January, and I had a photography exhibition at the original Circus of Books, West Hollywood, on April 1st — entitled APRIL FOOLS!

My photography is featured in a group exhibition, AllTogether: Artworks, archived at The Tom of Finland Foundation. This will be at La Biennale di Venezia during April and will arrive at The Community Centre, Paris, on May 8th — Tom of Finland’s 102nd birthday.

Thank you, Rick, for taking the time to answer these questions.

I thank you, Janis, for the thoughtful questions and research you’ve put into this interview, which has inspired me to contemplate my life thus far.

Janis Butler Holm has served as Associate Editor for Wide Angle, the film journal, and currently works as a writer and editor in sunny Los Angeles. Her prose, poems and performance pieces have appeared in small-press, national and international magazines. Her plays have been produced in the U.S., Canada, Russia and the U.K.

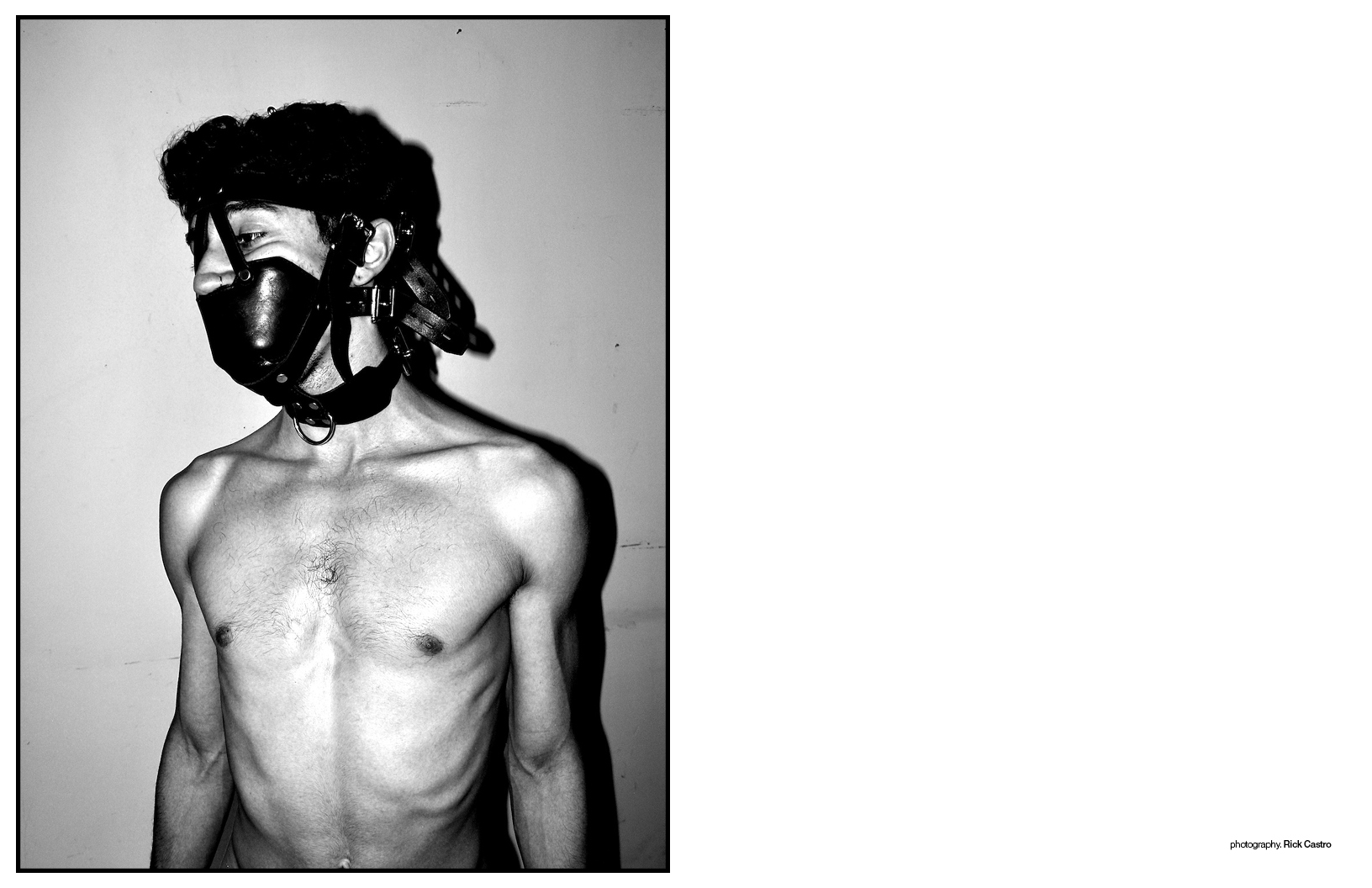

photography. Rick Castro

words. Janis Butler Holm

Schön! Magazine is now available in print at Amazon,

as ebook download + on any mobile device