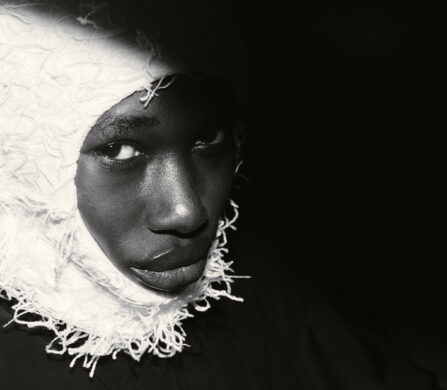

Luo Yang (罗洋) is the photographer capturing the faces behind the disrupting Chinese youth. Hailing from Shenyang, Yang is perhaps most known for her project GIRLS — a photo series capturing raw, intimate portraits of womanhood, no matter at what stage. Without a shadow of a doubt, GIRLS has catapulted Yang to global audiences, even making her one of 2018’s most influential women in the world, per BBC.

Living and working between Beijing and Shanghai, Yang’s gaze has long been set in her home country — capturing with ethereal and entrancing allure contemporary Chinese customs, with an eye turned to transgression. Much like the late Ren Hang or Lin Zhipeng (best known as 223), Yang’s work contributes to the reinvention of Chinese photography — one that expands horizon, defies stereotypes, questions gender norms and redefines femininity — particularly when seen through a Western scope.

Dancing between the lines of the infamous Chinese censorship, what started out as a means of personal expression, has seen Yang grow — literally and figuratively — one press of a shutter at a time. GIRLS has been an ongoing series for longer than a decade. But it has, until now, been restricted to China.

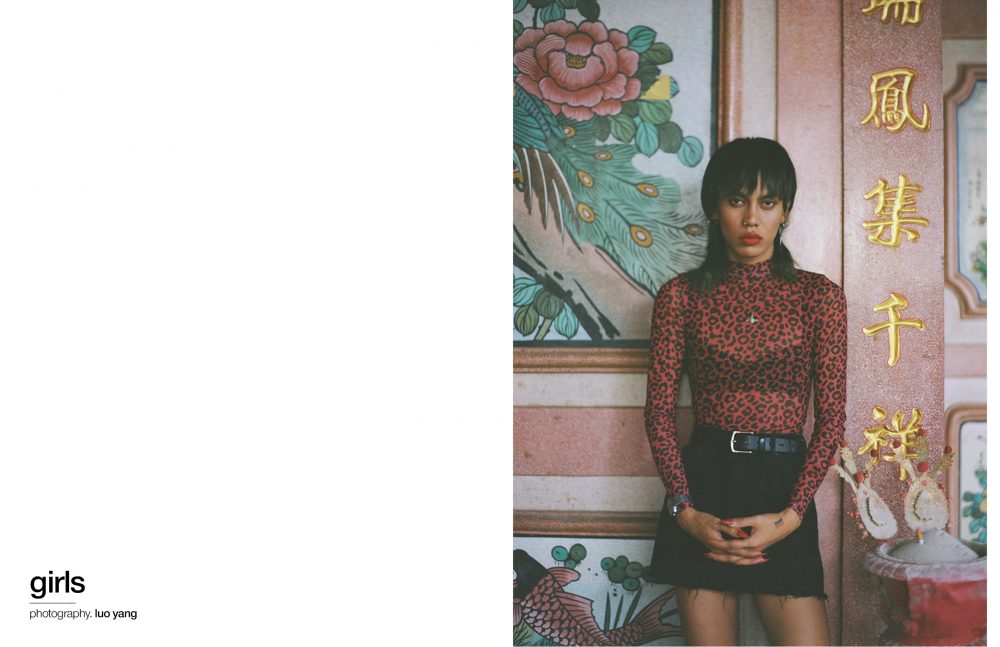

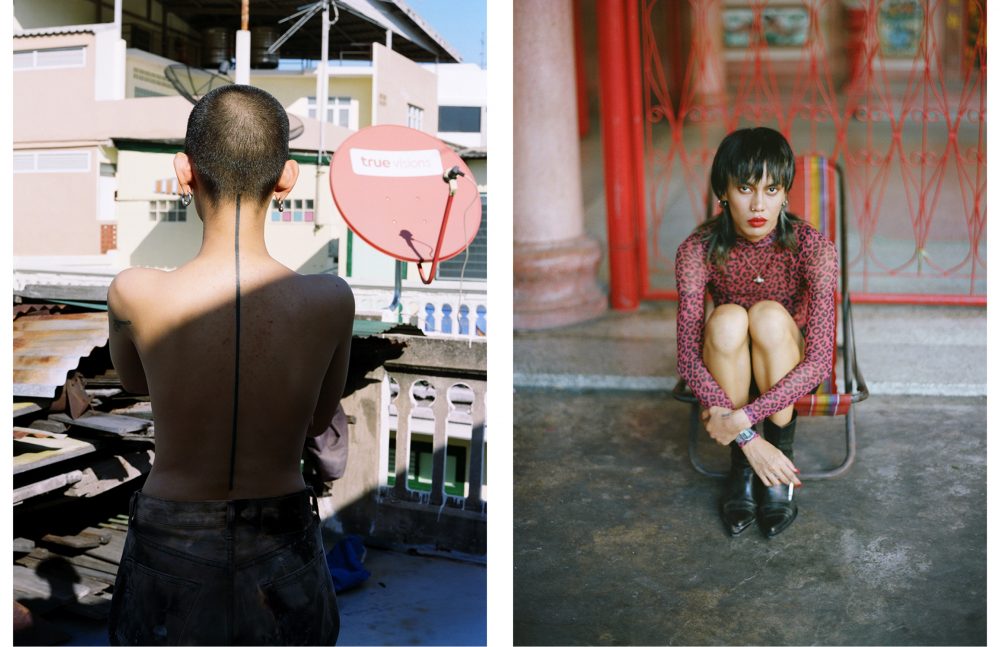

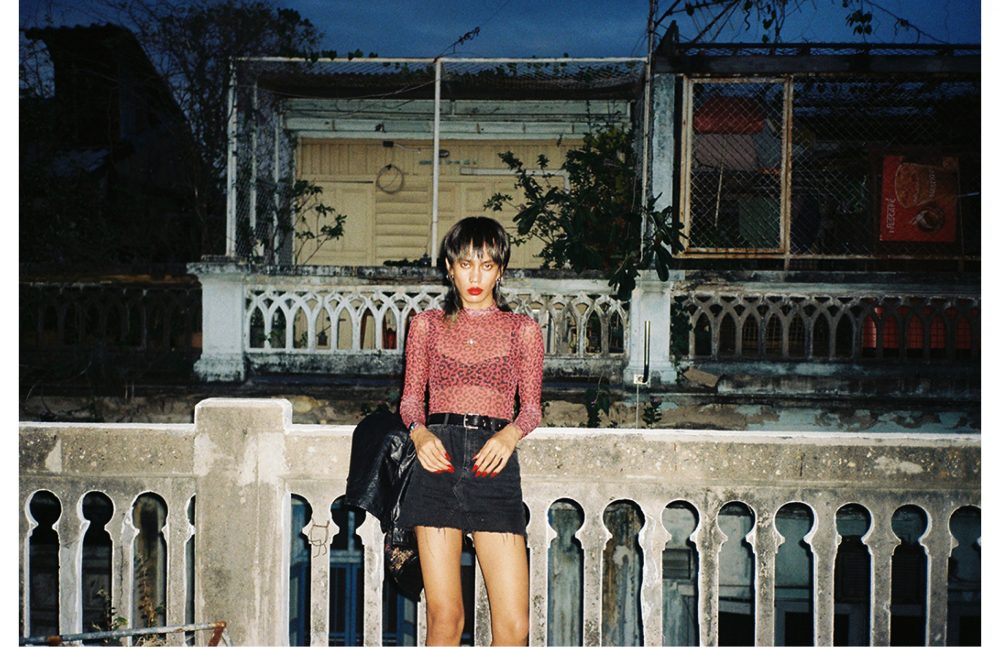

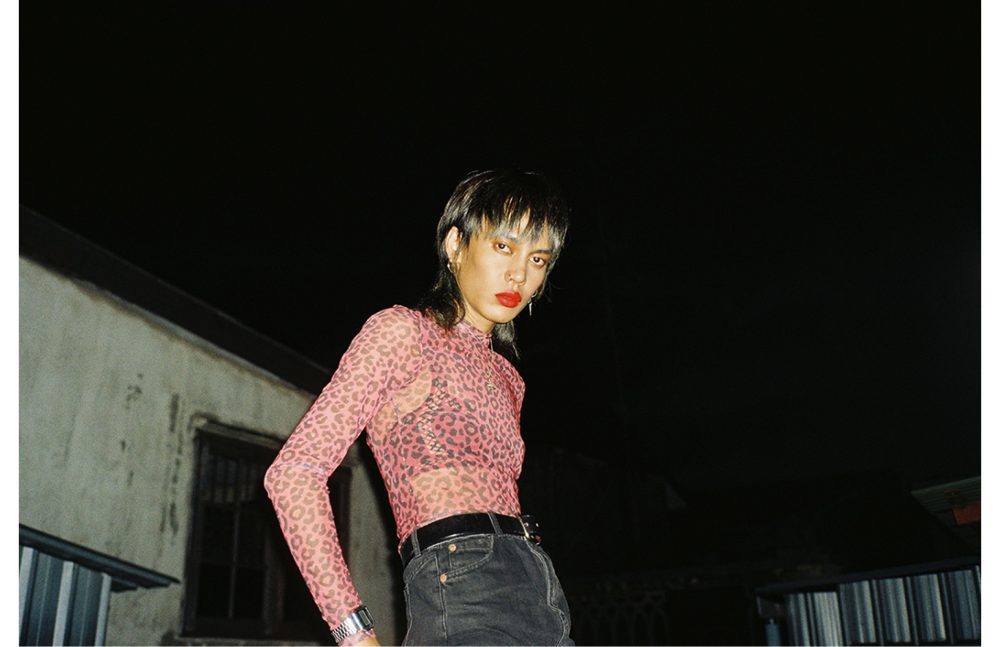

In December 2018, however, Moonduckling’s 10-year retrospective took her to Bangkok. “Before the shoot, I didn’t think Thailand as a place other than a very touristy country. However the people I met on this trip changed my idea,” Yang admits to Schön!. “I’ve got to know Thai people better, especially the [youth]. People still share great similarities despite the differences of their country. The Thai girls I shot this time, they are as fun and independent as Chinese young people, and they might share a very similar state of minds as well.”

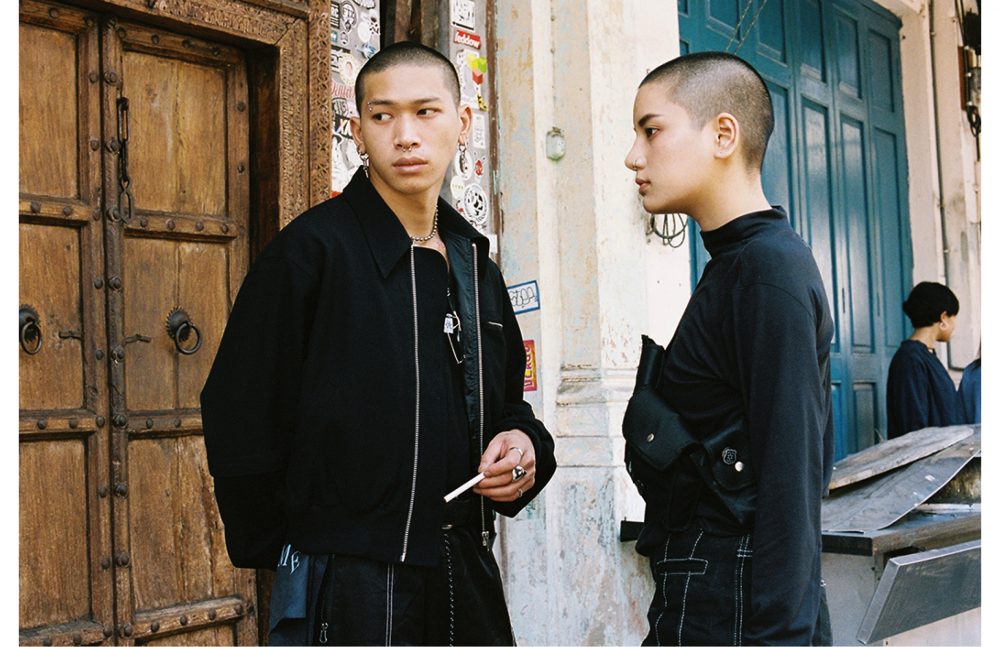

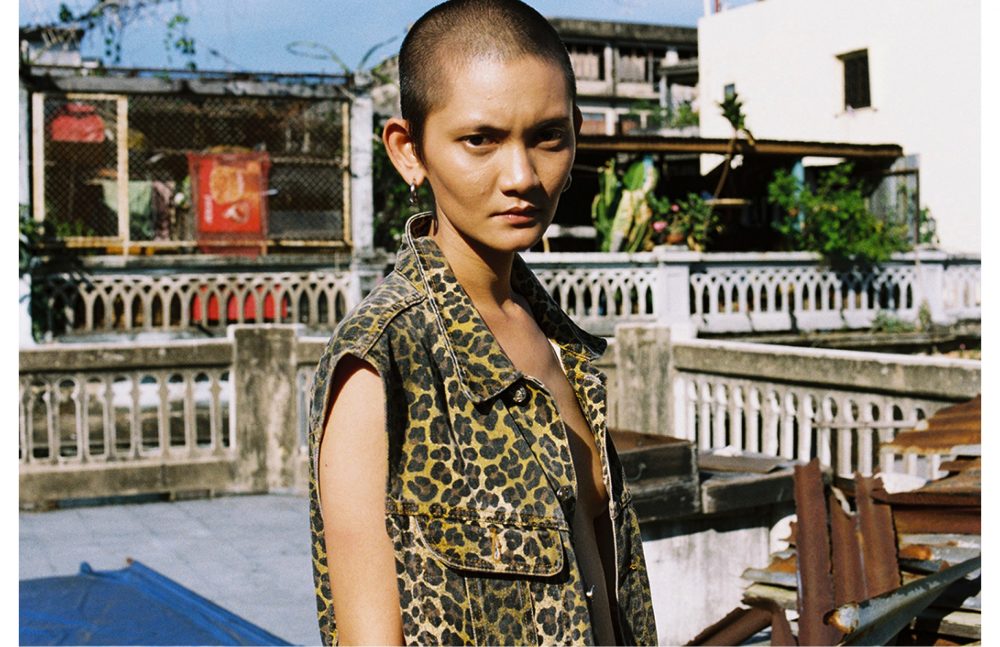

In the Thai capital, Yang found three (or technically four) new subjects: a trans woman that “ impressed” Yang “with her confidence,” a tattoo artist that “appeared to be shy and quiet during the shoot” and a young couple, whose “bond” Yang appreciated most.

“She doesn’t care what other people think about her, despite all the misperceptions of the trans group,” Yang recounts of her first subject. “She’s very good at expressing herself in front of the camera, simply because she likes the way she looks.” The second one, however, falls on the other side of the spectrum. “She was not very good at expressing herself, but I can feel she has a deeply hidden power inside,” Yang recalls. “She’s not as shy or fragile as she looks, she definitely has a very strong presence.” Last but not least, it’s the couple. “They are both bold, wear similar clothes, perhaps have the same pursuits or same value of life,” Yang narrates. “The girl is brave to shave her head and her action is respected and admired by her boyfriend. I feel their relationship is based on mutual respect and appreciation. They live free.”

Here, Schön! exclusively presents a selection of Yang’s snaps on Thai soil as we catch up with the lenswoman to discuss her earnestly powerful imagery, her upcoming “boys and girls” series, and how she hopes to continue challenging pre-imposed notions across the globe.

You are known for your photographs capturing womanhood. How did this become your main subject? Did you it come naturally or was it something you set out to portray?

I started photography in college, by taking photos of people around me and most of them were girls. At that time I also took photography as a way to release my own feelings. I tend to shoot people who share similarities with me so it naturally became a girls series. Basically, I want to record people’s touching and authentic moments, and now I’ve started a new series about the young generations in China, it includes both boys and girls.

You studied Graphic Design. When did you discover photography and when did you realize it was what you wanted to pursue?

It was in college when a friend lent me a simple point and shoot that I started photography and gradually realized that it was something I’d like to keep doing.

GIRLS has been an ongoing project of yours for more than a decade now. Do you ever see it coming to an end or do you hope to maintain it as long as possible?

As long as I keep taking pictures, this series won’t come to an end. I want to keep recording more people from various backgrounds and generations.

Where do you look for inspiration for your photographs? Do you feel it has changed in any way since you started out?

I take inspirations from anywhere in life. Other photographer’s good photos, movies, artworks… Life itself is my inspiration and this will never change.

With the recent retrospective, you had a chance to look back at your work over all these years in one place. Did you realize something about it seeing this? Did it feel cathartic?

I feel that I’ve changed a lot with the girls I shoot over the years. The reasons why I started this series, my own loneliness and confusions are gone, they went away with my own growth and disappeared as every shutter I click. Now I’m in a new stage in life, I have new things to deal with. Looking back, there are for sure a lot of feelings and I see movement in the photos I took, it is cathartic to some extent indeed.

You say you “depict a part of contemporary China rarely shown in the West,” capturing “women that challenge traditional ideas around femininity.” Do you feel these ideas have changed over time? Do you feel the West is somehow more “in touch” with this part of Chinese culture you capture?

I have to say the girls I shoot are the ones more pioneer-like, independent and self-awaken earlier than others. I still take pictures for girls that are somehow different, it’s just over time girls of different generations are different in various ways. And I think people are connected, they share the same emotions despite their nationalities, the West is also able to relate to my works very well, in ways they understand both life and art.

You live and work between Shanghai and Beijing, and this is where you’ve long photographed most of your subjects. However, these were shot in Bangkok. Did you find any differences between doing the project in China and Thailand?

I’m actually a bit surprised but more happy to find that Thai girls, or Thai young people, have a lot in common with the Chinese young people nowadays. They may look slightly different, but they are also fun and independent, have similar states of mind, similar confusions about themselves.

In all these years, the series and subjects have evolved and we have seen you shoot intimate friends and complete strangers. How do you select who you want to shoot?

It’s very flexible. I meet a lot of people and my friends will introduce some to me as well. If I bump into strangers who I think are interesting, I’ll also ask them to be my models too.

Do you keep in touch with all of your subjects?

I’ve shot too many girls. Some I keep in touch and shoot for them every year; some girls walked out of my life sometime later. But I think the connection is still there whether we keep in contact or not.

You work almost exclusively with 135 film. What do you feel film offers as a medium that digital can’t?

Film offers me more time to think before taking the picture, and it records reality. It presents absolute authentic moments, and that authenticity is what I’m trying to show in my photos.

Do you ever see yourself trying out the digital route?

I’ve started to explore films/videos recently. Perhaps that could count as a digital media…

You were named by the BBC as one of the 100 most influential women worldwide this past year. How does that feel? Do you feel influential?

To be honest, it was quite a surprise as the news only came the last moment. I don’t feel influential. I’m still doing the same things as I used to.

You said you set out to break the norms with your work. How do you hope to continue doing it?

I’ve been getting inspirations from many different places outside photography and I’ve been trying to find new subjects, exploring new series. I’ll continue doing these.

Lastly, what does censorship, a word that has sadly been tied to your work a lot, mean to you?

Censorship is a common thing that many artists will encounter. Like major SNS platforms such as Instagram and Facebook, all have policies about uploading nude photos. My works probably get censored because of nudity — but it doesn’t influence my work or my creation too much. It’s not my main focus, and there are other venues to make your work known to people.

All images courtesy of the artist and Moonduckling. Special thanks to Moonduckling.

photography. Luo Yang

words. Sara Delgado

Schön! Magazine is now available in print at Amazon,

as ebook download + on any mobile device