Armani / Armani Maestro Fluid Foundation

Mac Cosmetics / Retro Matte Liquid Paint Café au Chic

Lancome / Drama Liquid Pencil Nuit Intense

Benefit / 24 Hours Brow Setter Shaping & Setting Gel

Opposite

CHANEL / le Volume de Chanel Mascara

Tarte / Clay Pot Waterproof Eyeliner Crytsall Ball

YSL Beauty / Tatouage Couture Liquid Matt Lip Stain

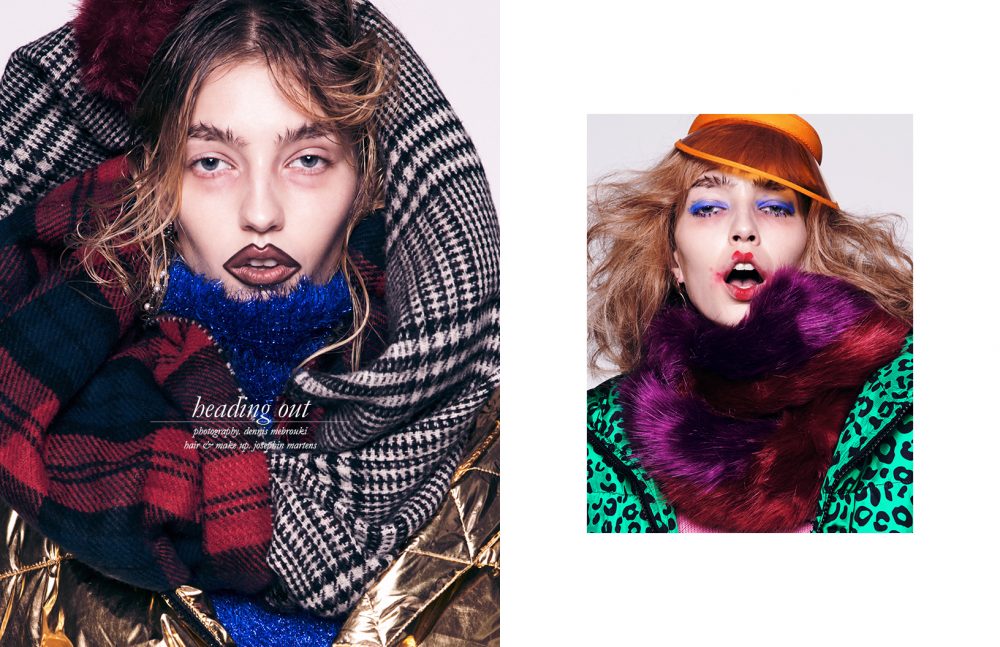

Photographer Dennis Mebrouki makes a statement with this bold Schön! online editorial. Models Eileen Heydorn and Thula are made up to the nines by Josephin Martens using the likes of Urban Decay, Nars and Marc Jacobs.

Tom Ford / Shade & Illuminate Cheeks Subliminate

Make Up Forever / Aqua Crem Snow

Laura Mercier / Transparent Loose Setting Powder

Opposite

Marc Jacobs Beauty / Highliner Gel Eye Crayon Eyeliner Blaquer

Nails Inc / Easy Chrome Nail Polish Steely Stare

Dior / Vernis Gel Shine and Long Wear Nailpolish

Pat McGrath Labs / Permagel Ultra Glide Eyepencil

Urban Decay / Partial False Lashes

MakeUpForever / Flash Colour Palette

Too Faced / Melted Latex Liquified High Shine Lipstick Twilight Zone

Opposite

Urban Decay / Glide on Eyepencil Black Velvet

Burberry / Effortless Eyebrow Definer

Nars Cosmetics / Blush Exhibit A

This Schön! online exclusive was produced by

Photography / Dennis Mebrouki

Models / Eileen Heydorn @ PMA, Thula @ PMA

Hair & Make Up / Josephin Martens @ Bigoudi

Hair & Make Up Assistant / Kristina Heinisch @ Bigoudi

Discover the latest issue of Schön!.

Now available in print, as an ebook, online and on any mobile device.