Photographer Niko Tampio’s new photo series depicts Barcelona’s ‘manteros’, the street vendors who hawk goods up and down the Barceloneta beaches and have become a mainstay of the city’s landscape. Named after ‘mantas’, the blankets on which they display their merchandise, these vendors are largely undocumented migrants shut out from traditional forms of work whilst they navigate the bureaucracy of settlement.

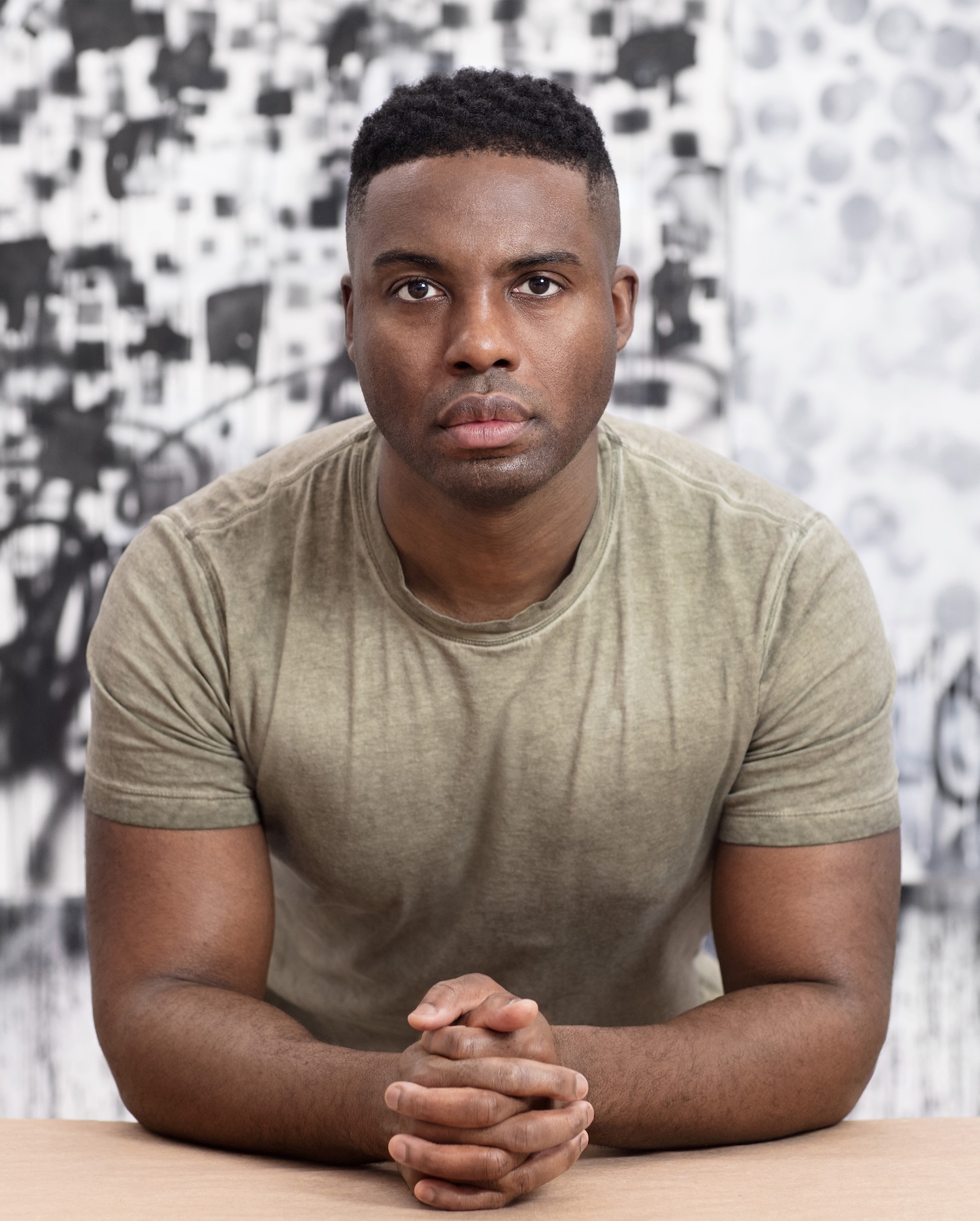

Like the humanist photography of the 20th Century, Tampio’s pared-back portraits are simultaneously a sociological and aesthetic exercise, illustrating the joy and community that persist despite economic precarity and anti-immigrant hostility.

Schön! alive spoke to the photographer about the inspirations behind the series, the responsibility of the artist and Barcelona’s dynamism.

How did this project come about and when did you first decide you wanted to represent Barcelona’s beach vendors as photographic subjects?

I’ve been going to Barcelona for years, and I’ve always gone to the beach and seen the manteros walking around. They have this singing voice when they’re selling that represents to me the sound of Barcelona, and I’ve always wondered about how their lives are.

They also interest me in a fashion sense, because I do a lot of fashion photography, and I like their clothing – I thought that they looked interesting – so, I decided that I had to do a project about them. I come from the working class as well, and I want to tell the stories of people from this background. There are many, many angles why I chose to do this project.

You mentioned that you spent a lot of time getting to know the subjects and forming relationships with them beforehand. Was there anything that you learned in that time that particularly stood out to you?

There were a lot of people that didn’t let me take photographs, so I don’t know what’s going on for them. But those people who were open to it, they are just like you and me. Many of them have come from Pakistan or Senegal, and because they don’t have papers, they have to do this kind of work, but they all dream about having a regular job in a restaurant, and they live just like you and me, even though they don’t have papers.

One thing that surprised me was how happy some of them were to be photographed. I gifted them the photos later and I saw how much happiness they got out of it because they felt seen. I think because somebody took the time to photograph them, the actual photograph meant a lot.

Even though it’s so hard, there are moments of connection or happiness that you can find in migration, and that really comes across in your photographs.

It was a really tight-knit community. People who were working close to each other knew each other by name, [but] when I went to the other side of the beach, I showed them pictures of the other guys and they were like, “Yeah, I know him.”

You mentioned before that some people didn’t want their photos taken. It’s difficult to represent undocumented people because there can be dangerous implications to their visibility. Was this a big concern for you and for your subjects when you were making this series?

Some of the manteros, especially those who didn’t let me photograph them, asked if I’m working for the police, for example. When I started the whole project, I didn’t even know if I could get any photos, but then I learned that some were really happy to be photographed. Some were strict, and I respect that. I understood that they didn’t want to get photographed, and I didn’t want to push it.

How did you try to represent the subjects with compassion and humanity?

Of course, I wanted to have my direction so that the photos look like they are in the same series – and the lighting and the time of the day dictates a little bit what I can do – but, basically, I let them choose the spot and choose how they posed. One guy wanted to sit under the umbrella, and one guy wanted to have something that was important to him in the background. I also took some pictures with their friends, all together.

I didn’t want to create any extra dramatisms from my side but just show them as a person and tell their story, and that’s why I didn’t want to take sneaky photos and stuff – I wanted to get to know them and build that relationship. I can call many of them my friends now.

They are very visible, but at the same time, I feel like they are kind of invisible. So, I wanted to photograph them as a whole person and show them as positively as possible, to lift them up, because I think photographs have the ability to make something more sublime, or put it in a good light.

The setting of the photos is evocative of those beach photos that Martin Parr did back in the ‘80s, yet very different because, of course, he’s depicting leisure and you’re depicting labour. Did you have any influences, photographic or otherwise?

I think the biggest inspiration is my background and my interest in my subjects, but I got really into photography when I was a super small kid. I grew up in the late ‘90s, early 2000s and I was looking at a lot of music album covers and fashion photography in magazines like ‘The Face’, and ‘i-D’, so a lot comes from there.

Also, Wolfgang Thielmans and William Eggleston…When people look at my photos, they mention either of them, so feel some kind of connection to those photographers. Estevan Oriol, who’s a LA-based photographer, has been really influential for me. I wanted to photograph my subjects in a similar, straight up style, and I think that gives power to these photos.

Did you consider your own experience of migration and movement whilst doing this series?

I think so. I come from a working class background, and my dad has been traveling for his job his whole life. And the same thing for me; I feel like moving is in my blood somehow. Because I’m an EU citizen, I can go to Spain and anywhere in the EU, so in that sense, I’m in a privileged position. The manteros come from Pakistan to Spain without papers, and they don’t instantly have the same opportunities. I often thought about how lucky I am to be able to do that. And of course, coming from Finland, I don’t need to escape from anything.

The working title – ‘the working class below the working class’, is an interesting sociological perspective. Could you tell me a bit about the naming?

A lot of people are talking about the working class and what it is. I feel like people tend to forget that there’s a class of people who really want to work, but they can’t because of bureaucracy and certain laws. Being from a working-class background, it was a struggle to get master’s degrees in arts and photography – it wasn’t really on the table for me to become a photographer. I promised myself a long time ago that if I have the opportunity to work as a photographer or artist and I have a platform, I want to dedicate a part of my work to give some type of voice to people, because I think that’s the most important thing. If I don’t talk about those who are struggling more than me, then what am I doing? I think [artists] should try to bring about something better than what already exists. And if you’re not making anything better, at least try to not destroy anything more.

Finally, I was wondering about your relationship with the city of Barcelona. How does your perception of the city inform your photography?

Finally, I was wondering about your relationship with the city of Barcelona. How does your perception of the city inform your photography?

For about 15 years, I’ve been living in the city and going there regularly. It’s been really influential for me. I also lived in Madrid for a year and I’ve spent time all across Spain, but Barcelona is a special place. Because I’ve spent so much time there, I know the dynamics, and I’ve seen how tourism has changed the city. When I went there 15 years ago, it was different than it is today, and it was also different after the pandemic.

I don’t know exactly why I got so into it, even before the first time I went there. When I was a kid, I liked ‘Miami Vice’ a lot and I didn’t have the opportunity to go to Miami, but then I heard about Barcelona and I was like, “This is in Europe and it looks kind of like Miami!” So, it created an obsession before I even went there. The first time I was there as a tourist, but then I got to know all the places and the people. It’s super vibrant and there are people from all over the world and from all classes. It’s hard to explain, but I love the city and that’s why I started to do this project about the people there.

It’s not been the easiest project to carry on. I spent pretty much the whole summer there, on the beach. I usually went there early in the morning, and back again in the evening to spend time with the manteros, so they got to know who I am. The most important – or best – part of being a photographer is that you meet people; you take their photo and you learn from them.

words. Soraya Odubeko

photography. Niko Tampio

Finally, I was wondering about your relationship with the city of Barcelona. How does your perception of the city inform your photography?

Finally, I was wondering about your relationship with the city of Barcelona. How does your perception of the city inform your photography?