A sumptuous but sanitised retelling of one of history’s darker moments

In 1947, the world witnessed its greatest refugee crisis when a staggering 14 million people were displaced and another million died. Many would say that this catastrophe was caused by the British and, yet, it’s a part of history that most Britons know very little about.

Excepting Richard Attenborough’s 1982 classic Gandhi and the 2012 adaptation of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, there have been few major English language films to tackle the Partition of India. Given the topicality of refugees and the violence that results from today’s racial and religious divisions, it is perhaps timely that British-Punjabi director Gurinder Chadha has chosen to take on this story on such an epic scale.

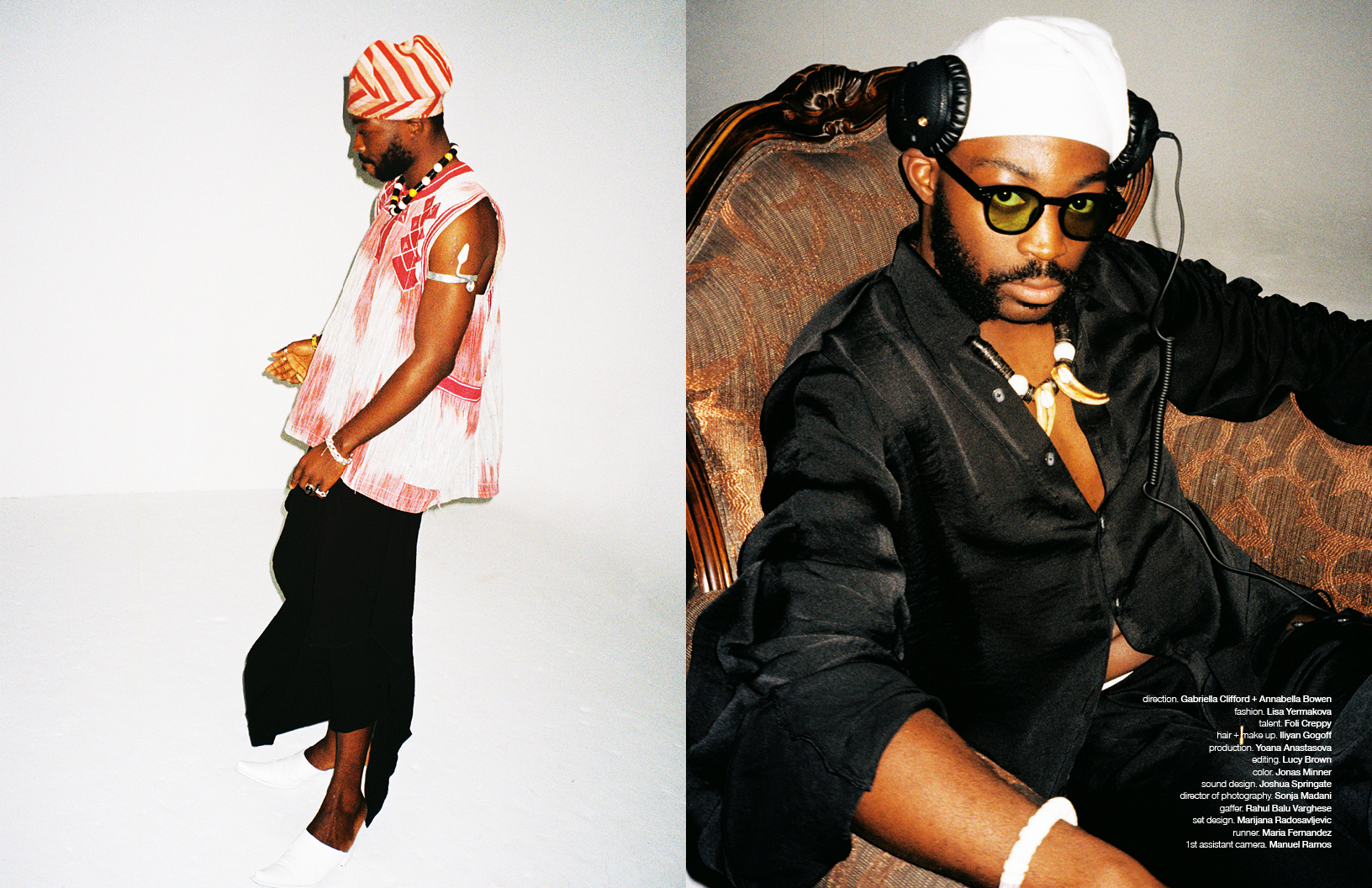

Image courtesy of Pathé International

Chadha tells us that her grandmother was “deeply traumatised” by her experience of Partition, to which she’d lost an infant child. “I’d never had the courage to make a film on such a sad part of my own history,” admits the director. “It was too dark.” When she finally decided to attempt it, she “wanted it to be about how the decisions upstairs that politicians took affected ordinary people.”

And so, Chadha focuses on India’s last Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten (Hugh Bonneville), and his extensive household. Accompanied by his wife (Gillian Anderson) and daughter (Lily Travers), ‘Dickie’, as he was known to his friends, has just arrived in Delhi to take on the unenviable task of overseeing the British Raj’s departure after centuries of Imperial rule. We follow his attempts to negotiate with Indian leaders Nehru, Jinnah and Gandhi, as well as the British Government, but the film focuses as much on the ordinary Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims that work in his gargantuan residence, particularly Jeet (Manish Dayal), a Hindu valet, and Aalia (Huma Qureshi), a Muslim translator, whose Romeo and Juliet style love story provides the main sub-plot.

Image courtesy of Pathé International

There’s therefore an Upstairs, Downstairs vibe going on. One feels like one’s watching the lovechild of Downton Abbey and Indian Summers and wonders if Viceroy’s House might not have been better suited to Prime-Time television drama, where it would no doubt have been a huge hit on either side of the Atlantic. Bonneville is more than competent in the role of Mountbatten, but barely distinguishable from Downton’s Earl of Grantham, although Chadha reminds us that she began working on the script before the TV sensation hit our screens.

The first act is rather slow, partly due to the quantity of characters to be introduced, but also because it attempts to explain the complexity of the political situation, which it does in rather clunky fashion, relying on dialogue for speedy exposition. The cast, which includes heavy weight actors such as Michael Gambon, Simon Callow and the late Om Puri, carries us through this, and the pace does pick up, as the consequences of partition unfold and we move from the opulence of the Viceroy’s House to the dust and confusion of a Delhi refugee camp.

Chadha’s unfalteringly flattering portrait of the Mountbatten’s is controversial but, without giving away too many spoilers, she says that it is based on evidence she uncovered through meticulous research that suggested Dickie “was not the Machiavellian architect of Partition, but a man caught up unwittingly in a bigger political game.”

Image courtesy of Pathé International

There are also too many elements missing to make this an entirely satisfactory historical depiction – an obvious omission is any mention of the alleged affair between Lady Mountbatten and Nehru. For a film that attempts to help people understand “the direct consequences of what can happen when you promote division: death, destruction and violence,” it shows very little of any of these. Instead, we learn second-hand about the slaughter of entire villages, the slaying of train-loads of fleeing migrants and the suicides of girls avoiding abduction. This was a deliberate choice on the director’s part. Chadha did not want to “risk alienating a broader audience”.

Instead, she hoped to make an “epic, populist film… to reach out to the broadest audience possible and remind them of this hugely important event that has been largely forgotten,” and this is exactly what she has achieved. Viceroy’s House is epic in scale, with sets and costumes that will delight most period drama fans, but retains a domestic intimacy à la Downton, and the casting is very pleasing. Its finest moments, however, lie in its humour – comedy is, after all, the stomping ground of the director of Bhaji on the Beach, Bend it Like Beckham and Bride & Prejudice.

Image courtesy of Pathé International

Viceroy’s House may offer a rather romanticised view of the Mountbatten’s and, indeed, the British Raj, but it is watchable, entertaining and goes some way to reminding us that, 70 years on, humanity is perhaps repeating the same mistakes.

Viceroy’s House is in cinemas on 3rd March.

Words / Huma Humayun

Follow her on Twitter