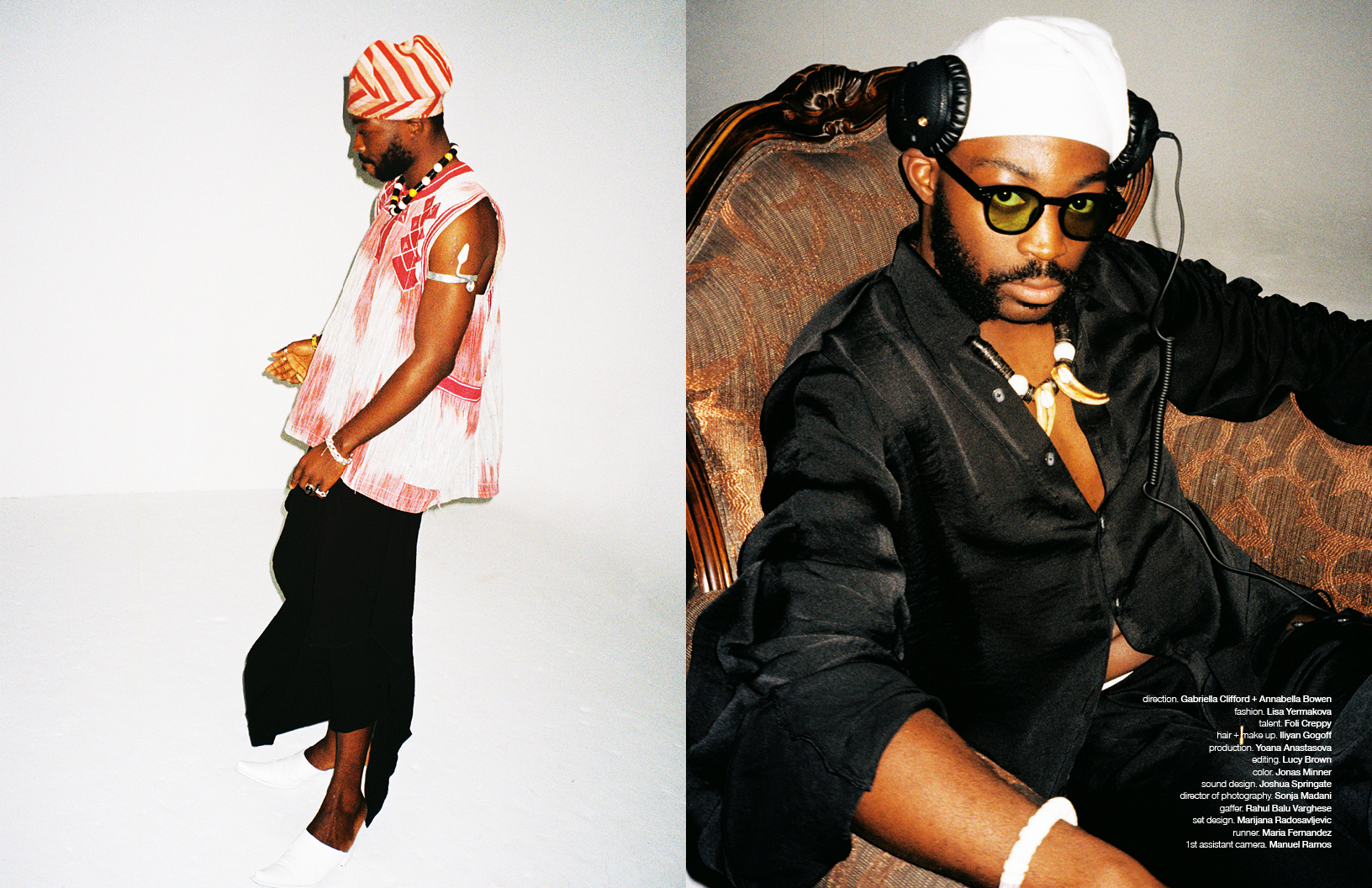

Angelina Jolie has tattoos of the geographical coordinates from the locations where her children first entered her life. Marc Jacobs is covered with modern day references, from Elizabeth Taylor in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, to that yellow sponge we all know as Squarepants. Then, there is Rick Genest, otherwise known as Zombie Boy, who you can catch in full tattooed glory in Schön! Issue 14. Fashion, music, design, advertising, and the media have been quick to appropriate the “tattoo phenomenon,” and we have lost count of the number of stars who have given in to it.

The new exhibition Tattooists, Tattooed at Musée du Quai Branly in Paris bears witness to the entire contemporary and aesthetic range of tattoos. By exploring 300 historical and modern works from a variety of countries, the exhibition presents an informative artistic dimension of the practice throughout human culture. Founders of art magazine Hey! Modern Art & Pop Culture, Anne & Julien, curated the exposition of tattoos, a subject of fascination and identity.

Tattooists, Tattooed highlights the innovators of the modern era – the “heroes” who have helped pioneer the development of the tattoo. Thirteen silicone “body extracts,” imprints that were cast on live models, have been specially developed for the occasion with special effects workshop Atelier 69 and validated by President of the National Union of Tattoo artists, Tin-tin. Scattered around the later part of the exhibition, we see silicon legs, torsos, and arms fully decorated with tattoos.

At first, we are introduced to the beginnings of tattoo. Encased in glass boxes are real arms and skulls with markings on them. There were human beings who painted themselves, or had themselves painted, long before permanent ink came about.

As the exhibition progresses, we come across portraits of Armenian women, slaves or prostitutes. Next to these pictures is a portrait of a 12-year-old boy, a survivor of a concentration camp. Tattoo was a mark of identification. Until the 19th Century, tattoos were signs of social exclusion, evidence of a marginal life. More than that, Christianity repressed the practice in Europe. A prison tattoo machine is displayed in the exposition, acting as a reminder that tattooing was a way to mark criminals.

However, from the 15th Century, during the era of great explorations, Western travellers in Asia, Oceania, and the Americas rediscovered tattooing. While its presence referred to the criminal underworld in Asia, it was an indication of social status among the people of Oceania. Tattoos then became a staple for voyagers, sailors, and adventurers.

A large chronological timeline in the exhibition shows that there was a great presence of tattoos in Japan and USA. In Japan, they were used as punishment starting from the 17th Century. The tattoos irezumi marked the place or the crime that had been committed and the nature of it (fraud, extortion, etc). As times changed, so did the ink. Tattoos in Japan became ornamental. They began to cover all or parts of the body like sleeves. Iconography came from nature, Japanese folklore, and the religious realm.

The birthplace of the groundbreaking electric tattoo machine was the United States. It was the first country to remodel the allure of Japanese ancestral art into creative energy. This artistic impulse fueled the spirit of research that pioneers needed to create new techniques. This made tattooing advance in the United States more rapidly than any other Western country. Previously frowned upon, the tattoo in Chinese society today opposes the prohibitions of the Cultural Revolution. It juxtaposes the longings of a novel generation: a past to be relearned and a future to be designed.

At the beginning of the 19th Century in Europe, people took matters into their own hands and tattoos became a choice. It developed into the underground dialectal of a kaleidoscope of originalities brought together around the practice of challenging generalisation and holding claim to its marginalisation.

Some tattoo artists draw from the traditional genres like the Japanese irezumi, American old school, or the wild vein of Russian gulag. Others express aesthetics that are freed from current codes to study the potentials linked to graphic arts, in which typography, pixels, and frames make other patterns, going as far as abstraction. Nevertheless, both have communicated a steadfast determination to reinterpret tattooing and its codes to offer a fresh aesthetic in our world today.

Tattooists, Tattooed is on show at Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, France from now until October 18, 2015. For more information, click here.

Click the links below for the latest issue of Schön! Magazine

Schön! in glossy print

Download Schön! the eBook

Schön! on the Apple Newsstand

Schön! on Google Play

Schön! on other Tablet & Mobile device

Read Schön! online

Subscribe to Schön! for a year

Collect Schön! limited editions