Artist Lorna May Wadsworth has certainly painted some serious subjects, from politicians Margaret Thatcher and David Blunkett, to a reworking of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. But this time around, Wadsworth indulges in her predilections to all that is light and glib with ‘100 Pictures 100 Pounds’. The online exhibition – which launches today – brings together long forgotten artwork and allows fans to snatch up their own Wadsworth original for only £100 pounds. Schön! caught up with the artist to talk about the collection, the ‘insidious’ relationship between art and money, and much more…

Are there any themes running through this collection, or are they 100 stand-alone pieces?

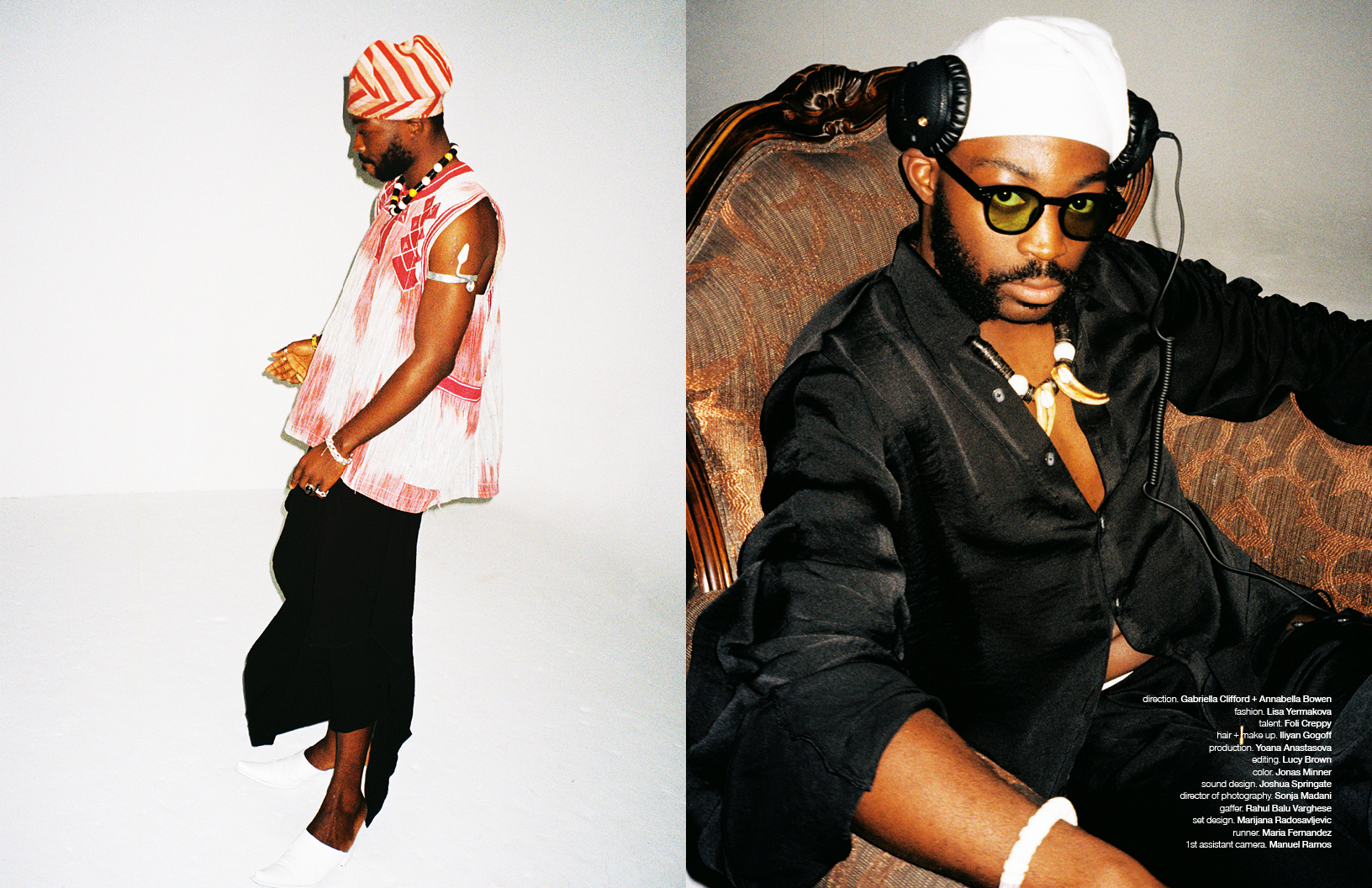

Fashion as a subject certainly appears front and centre in this latest collection, which reflects how the iconography of certain fashion houses has become intrinsic to the paintings I’ve been making recently.

The subjects of these pieces seem to be more diverse, from fashion to landscapes. Did this collection provide a welcome break?

For me, because there is parity between every piece, I feel a freedom to make pieces which I would normally censor myself from making – things that are pure fun; that I wouldn’t do in my wider practice as it might seem too populist. So I guess you could say it is a welcome break.

The collection utilises an impressive range of disciplines. Where do you feel most comfortable?

Since I discovered oil paint, I’ve never really looked back.

You have always been candid about painting through a ‘female gaze’ and celebrating male beauty. Do you see this as a matter of importance, or something that manifests itself naturally?

Well I think it’s important and I think it’s natural, but the patriarchal order of things has negated the female gaze from time immemorial.

You prefer to work un-commissioned so your work is not mediated by a controlling body. How detrimental do you think the relationship between art and money has become?

I see a relationship between art and money [as] insidious: conflated, craft-less tat masquerading as works of insight and significance, insider trading as standard, fools easily parted from their ill-gotten gains making the perfect capitalist system of value added nonsense.

100 for 100 is based on a first-come, first-served basis, so in theory everybody has the same chance of buying or collecting a piece. How early on was this platform for the collection decided? Is it an overt attempt to broaden your access to a wider market?

I had some old work I wanted to liberate to interested parties and I thought that making a collection of pieces of all sizes and mediums available at the same price, presenting them online in a format where they all appear the same scale on screen would mean that people were free to buy for love.

Your works are available online only. Do you think not seeing the works in person may be a deterrent for some potential buyers?

It would be impossible to do at the price they are if exhibited in the traditional sense. This way, they’re not subject to framing costs and gallery commission. And buyers can browse through them in the intimacy of their own laptop or computer.

You have painted a portrait of Lady Thatcher and members of the 2003 Labour Conference Party. Are you drawn to politics with your art?

After Lady Thatcher, I pretty much hung up my political palette. There’s nowhere else to go in terms of figures who embody living political history, aside from Fidel Castro, who I would absolutely LOVE to paint, but that is proving to be a little tricky!

You painted a version of The Last Supper with Jesus as a black figure, and your exhibition ‘Sacred or Profane?’ dresses monks in hoodies. How important do you think it is for contemporary art to reinterpret and redesign older concepts to reflect the current climate?

All art is in dialogue with the art that preceded it. I think it’s important not to produce high-class kitsch – like the stuff you see in ateliers in Florentine academies where they try and teach people to paint like the Old Masters, but without any content. They are just copies, appropriations of a style stuck in nostalgia. I want to take that kind of old school painting, but imbue it with a sense of commentary about the world I see around me.

What is the next step for you after this collection?

I am working on a body of paintings which explore the aesthetic of Tom Ford’s film A Single Man with my muse, fashion model Joachim Gram. Stylistically, they reference both Lucien Freud’s and David Hockney’s portraits from the seventies. I will also be working on the Fashion Martyrs, my work playing with the iconography of Chanel and Hermès.

Check out Lorna May Wadsworth’s 100 Pictures 100 Pounds at http://www.100pictures100pounds.com/