Lima-born Milagros de la Torre is a celebrated New-York based photographic and conceptual artist who enjoys a growing popularity and critical acclaim, particularly in New York, and her work features in the America Latina, 1960-2013 exhibition at the Fondation Cartier in Paris. Employing a deceptively simple, pared-down aesthetic, her visual language is highly philosophical and intricate which results in a powerful impact weeks, days and years later. Schön! spoke to the artist about her practice, her work in the upcoming exhibition, on being an outsider, and on connecting and finding common ground in her work.

Could you tell us a little about your biography? How did you come to focus on photography?

I was raised during the 70s and 80s in Lima, Peru, in the midst of economic instability, military dictatorship and later on, under the power of an armed terrorist movement. My mother worked as a History teacher and my father followed the military family tradition. Both of my grandparents also wore armed force uniforms.

From an early age, I was certain that I was going to dedicate myself to a different line of work; I imagined a different place, a door to ‘somewhere else’.

What are the biggest influences in your work?

As I start to focus on proposals and new series, I’ve come to recognise various influences in my work. It’s inevitable that experiences, personal or professional, end up focusing my work on particular topics.

I’m also conscious that my background plays a strong role. As a child, I was surrounded by books about criminology, police documentation, bio-metrics and mug shots, organised crime language and codes.

What does a photograph represent for you?

A space with the capacity to evoke and generate thought.

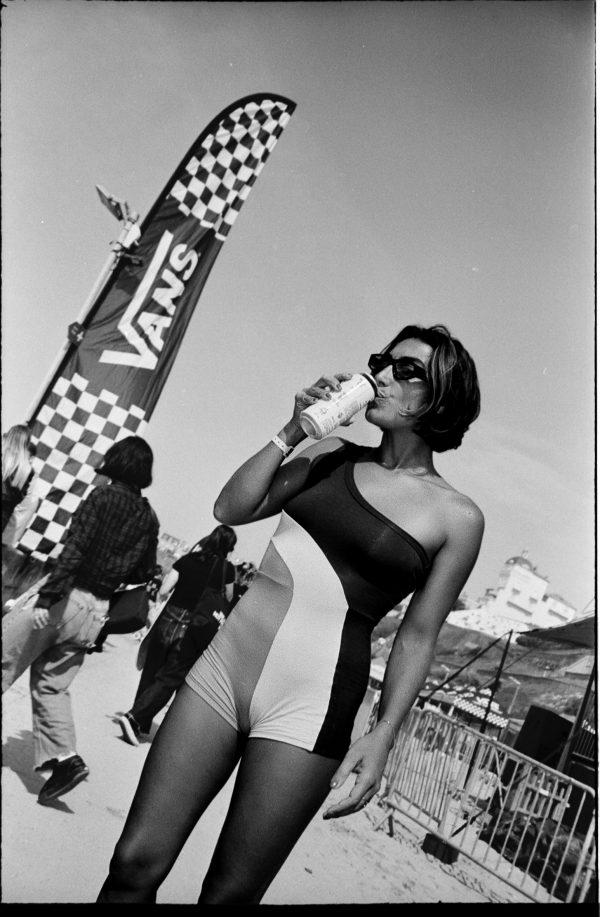

Milagros de la Torre, Antibalas (De vestir, dama), 2008

Courtesy Toluca Fine Art, Paris

© Milagros de la Torre

You have previously stated that “trusting the photograph is a huge mistake.” Does your aesthetic serve as a critical warning to the viewer not to take things at face value?

Yes. Simplicity is hard to achieve and not everyone is attracted to it. My premise has always been to propose implied signs, hoping the reader would exercise and involve his/her own analysis. The ‘real photograph’ is the space in-between the readers’ mind and the proposed image.

We have come to the point where we acknowledge and realise that photography was never a trustworthy document, but rather an interpretation; it never referred to what we were actually observing in it, but it referred to our reaction and our response to its stimuli. An image has to be de-coded.

By taking the body out of Bulletproofs, do you warn the viewer not to neglect the human, not to undervalue the brutality of war?

Indeed, the fragility of the body and its psychological depth are implicit in the garments. Historical amnesia is also implied.

The series comprises representations of apparently innocent, unsuspecting everyday pieces of clothing. Suspended in vacant white spaces, depicted in high detail, these well-crafted garments conceal their real purpose: to protect the wearer from attack by firearms.

The work is emblematic of our times, where there is an increasing militarisation, an overwhelming mechanics of violence and a climate of insecurity. These are terms I can relate to because of my upbringing in Peru; unfortunately they have global relevance today.

There is a real corporeality to Bulletproofs and to many of your other works. How does this fit with the photographic form? Do photographs have their own corporeality?

As any object, photographs relate to the corporeal, too.

I am interested in the notion of ‘layering’ within an image, as in a layering of related concepts – from historical or technical references, to semiotics or associated studies. In a few series I have used ink, wax, and tint on photographs or have photographed these layers directly. These layers work as signifiers and hopefully help decipher the image.

The exhibition America Latina, 1960 -2013 at the Fondation Cartier in Paris seeks to situate Latin American photographic artists within a complex cultural history, from the 1960s until the present day. How does it feel to be in such a wide-ranging exhibition?

I have always been an outsider, an expatriate, even in my own country. I have never belonged to a specific group of artists in any of the cities I have lived: I was always peripheral, always alien. But in this exhibition, I have the sense that somehow all the works share common ‘grounds’, and that was satisfying.

What works of yours feature in the exhibition?

The curators decided on the Bulletproof series, choosing a couple – a female and a male garment. Upon close inspection, a few words, reveal themselves as a clue, on the clothing label, and indicate the level of armoured protection: PLATINUM (long-distance automatic weapons), GOLD (pistols, revolvers) and SILVER (blade and common weapons).

What comes next?

More research, more challenges and I want to continue observing my daughter growing up.

The exhibition America Latina 1960-2013 is now on at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, until April 6th, 2014.

Words / Edward Ball