Creating a vent for the raw emotional landscapes of those suffering from mental health issues is what Crowns & Owls’ freshly released project, WIT H IN, has set out to do. Consisting of a short film, a photographic series and a book publication, the visually captivating project is driven by a desire to reignite the debate around mental health, with revenues from WIT H I N going to UK mental health charity MIND. Having previously catered for the likes of Ted Baker and music band Hercules and Love Affair, the London-based creative trio are altering their course into exciting new and important directions with WIT H IN. Here, we chat with Crowns & Owls about their unashamedly personal investments into WIT H IN, the power of art that’s more than skin-deep and the trio’s brotherhood culture.

With three minds behind Crowns & Owls, how do you find collaborating alongside each other?

We started out as friends, so the dynamic between the three of us comes from a very organic place. We’re often told we behave like a single organism, which is actually quite a creepy thought. There’s a very coherent taste between the three of us, so things are usually pretty seamless. This particular project was interesting in relation to this question, as it was self-initiated, self-funded and very much predicated on our individual relationships with mental health, which are very different. We have depression and anxiety operating on different levels between the three of us, so the real challenge with this film was crafting something which speaks for each of our experiences whilst remaining as a single, coherent piece for a cause which is much bigger and more important than ourselves.

You’ve done quite a few music videos and fashion films – including for Hercules and Love Affair and Ted Baker. How did the change to working in tandem with a charity come by?

It felt like the right time to do a personal project, and the past 12 months have been quite testing in our private lives. Mental health and wellbeing is something which has played a huge role in our lives and is something which unifies us. We’d started to be much more transparent about this subject matter to each other, and it was that openness which gave birth to WIT H IN. We approached Mind and told them we’d like to do this project as a donation to them, as Mind as an organisation was there when we needed them. The project itself consists of a film, a photography series and a book, from which all proceeds are donated directly to the charity.

There’s an almost ethereal sensibility to WIT H IN which, paired with an emotional nakedness, leaves the viewer feeling melancholic after watching. Was this intended?

Reactions to the film seem to go one of two ways and seem to be largely governed by the viewer’s relationship with the subject matter. Some people find it empowering and say that it articulates their experience, whilst others find it deeply saddening and shocking. We think the reaction leaves something to be said for the mental health topic in general, which is inarguably becoming a silent epidemic in this country — it’s not something that many people talk about, but it’s a growing problem that affects a huge number of people. Ultimately the film’s intention is to highlight how vital organisations like Mind are — by hopefully transcending the viewer’s relationship to the subject by taking them on a visceral journey.

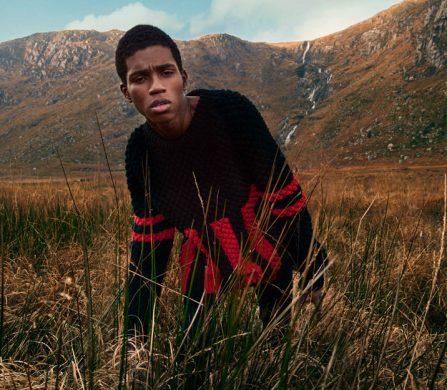

There is an undeniable beauty central to the film: that of the outer landscape mirroring Dennis’ mindscape, almost empathising with him. How important do you think are empathy and understanding to curing depression?

Empathy is hugely important, and we believe rediscovering empathy is one of the most important things we should be collectively working towards as a society when dealing with this issue. We feel it’s important to say that our personal conditions are on the more socially palatable end of the spectrum of mental health, but they’re the tip of a much larger iceberg. It’s about learning to be more empathetic to people suffering from the myriad of conditions which go beyond just depression, anxiety and PTSD. These conditions are difficult to navigate from an outside perspective, but living in a metropolis like London exposes you to these people on a daily basis. There’s a lot of ways you can help — looking at volunteering for one of the many critically underfunded mental health charities is a huge step you can take on a personal level.

Your impressive set design has a staged-ness reminiscent of an abandoned coliseum. What was your experience working on the set?

The film was shot with a very small, compact crew — literally 5 people (3 of which were us) and Dennis. It was made up of people who have an interest in supporting this subject, so there was a brotherhood in the whole experience. The locations were very remote, and the shoot itself was very physically demanding. It was a raw, rugged experience, and hugely challenging, but we feel the experience of the shoot itself can definitely be felt in the finished film. Our goal was to make a piece which was relatable on a primitive level — everyone can relate to the feeling of being cold, everyone can relate to the feeling of being lost and the locations/design are intended to reflect that as closely as possible.

How did you go about researching WIT H IN?

We adopted a brutal honesty when making WIT H IN; there’s a lot of us in this piece — even the dialogue is built from a group therapy session between us. We figured the best hope to obtain an emotional reaction was to imbue the film with as much transparency as we could with our own experiences. We aimed to let feeling lead the way with this piece, rather than thought. A lot of our education [on] the subject of mental health has come from our own experiences, and in turn by seeking help.

What your film captures with great subtlety is the disconnect between body and mind: even while the body attempts to strive, it’s reined back by the fetters of the mind. How did you envision and research the body-mind relationship when it comes to depression?

It’s lovely to hear that this has come across. Again, we placed trust in our day to day experiences to lead the way with this. There was always the risk that perhaps our experiences would be difficult to relate to, but we placed confidence in the fact that one of the big obstacles to navigate when you’re dealing with mental illness, is getting past the illusion that you’re the only person that feels this way. For us, making this project has reaffirmed that this is not the case.

According to recent studies, female depression is more prevalent, and yet, you went for male model Dennis Okwera to embody the vicious circle of mental illness. Do you think gendered depression exists? And if so, why did you decide to spread the word about male depression in particular?

Gendered depression exists, without question. How each gender deals with mental health is starkly different and there’s a multitude of contributing factors which play a huge role in how this is navigated; biology, society and culture, to name a few. Ultimately, we’re writing what we know — we’re three men. One of the things which have been most interesting since we released the project is how women perceive it. More often than not, the piece seems to transcend gender, which is so humbling for us as that was a huge ambition of ours for the film.

We had a woman come up to us at the screening of the film, and she talked about how, in her experience, the way in which women interact is a form of therapy in itself — she explained that more often than not, her female friends don’t just ask how she’s feeling, but go deeper and try to help her figure out why she’s feeling that way. This second question, generally speaking, is something men just don’t really ask each other. It does make you think about how this division might contribute to the ratio of male to female suicides, which in a 2015 study was revealed to be 75% male to 25% female.

Do you see art as a medium to steer social debate? If so, how effective do you think it is?

We feel that art has always been, and continues to be one of the most powerful tools within social debate. The real challenge in the modern world is making something impactful enough to battle our increasingly shrinking attention spans. In our opinion, film is still the best tool to make somebody really feel something. If you can emotionally affect people, you have a good chance of making your point resonate. If we manage to do that with WIT H IN, we’d be genuinely elated.

Last but not least, what other projects have you got underway at the moment?

We have the drive to take WIT H IN further, we just want the film to be seen, career ambitions aside. So far, the reactions to the piece have compelled us to try and spread the project as far as it can go. After that, we have some ideas of how we can further this narrative. Time will tell.

Visit mind.org.uk/ to find out how you can help in the fight for better mental health.

All images courtesy of Crowns & Owls

writing + direction. Crowns & Owls

starring. Dennis Okwera + Nicole Harvey

director of photography. Adam Barnett

sound design. Ed Downham @ Wave Studios

additional sound design. Ned Sisson @ Wave Studios

edit. Crowns & Owls

music. Small Press Music

1st ac. Phil Herron

voiceover. Daniel Blake

colour. Jonny Tully

vfx. Pete Hughes

post-production. Hannah Whitehall + Emma Shuter

Crowns & Owls would like to thank the following for making this film possible: Arri, Big Buoy, Cinelab, Greenkit, Iconoclast UK, Kodak, Panalux, Panavision, PixiPixel, Small Press, Wave Studios

interview. Jenny Elisabeth Bär

Discover the latest issue of Schön!.

Now available in print, as an ebook, online and on any mobile device.