American figurative painter Jansson Stegner is known for a hyperreal, highly stylised aesthetic. His work offers a clear social commentary and presents subversions of gender and power. Peppering his canvases with hidden references, ranging from Old Master painting to Pop Culture, he features in the current Saatchi exhibition, ‘Body Language’, where his works present a moral challenge to the viewer. Schön! spoke to Jansson about painting as a medium, about storytelling, subversion and hidden narratives.

How did you come to be a painter?

I grew up reading and drawing comic books. When I grew out of the subject matter of comics I was still in love with image-making. About midway through high school, I started to realise that the images in my parent’s Art History books were much more interesting than anything I had been looking at.

Your paintings seem to allude to a lot of historical painting genres such as Mannerism. Could you talk a bit about your influences?

I have always liked paintings that are rooted in Realism without actually being realistic. My favourite painters are the figurative artists who are a bit off. El Greco, Otto Dix, Balthus, Alice Neel. They mess with the traditional rules of figuration to create a heightened psychological experience. An experience that takes the subject out of confines of ‘ordinary’ Realism. I like weird figurative painters.

Has painting ‘run out of energy’, or is the complete reverse true?

Painting may die some day, but it isn’t dead yet. To me, the nadir of painting was the 1970s. That’s when painting seemed most likely to die. It was almost suffocated by the ever more puritanical ideology of late modernism. Fortunately, most painters eventually discarded the overweening theory and started to have fun again. Painters today are free to do whatever they want. In that sense, painting is vibrantly alive.

Do you think painting really needs to continually justify itself as a medium?

I don’t think painting needs to justify its existence today. I think that humans are a long way away from turning their back on two-dimensional still images. Painting is a technology for making images. In fact, it is still the best technology available for certain kinds of image-making. Painting can do certain things better than photography, Photoshop or anything else, and as long as that remains true, painting’s existence remains justified.

I’m interested in the use of ‘Unreal’ in the previous Saatchi show title: where do your works sit in terms or real and unreal?

As I mentioned earlier, I like painting that is rooted in Realism without being a slave to it. I like to recognise what I’m looking at in a painting, but I also want to see the subject in a new and exciting way that isn’t as predictable as optical realism can be. So, ‘Unreal’ feels like an apt term to describe my work.

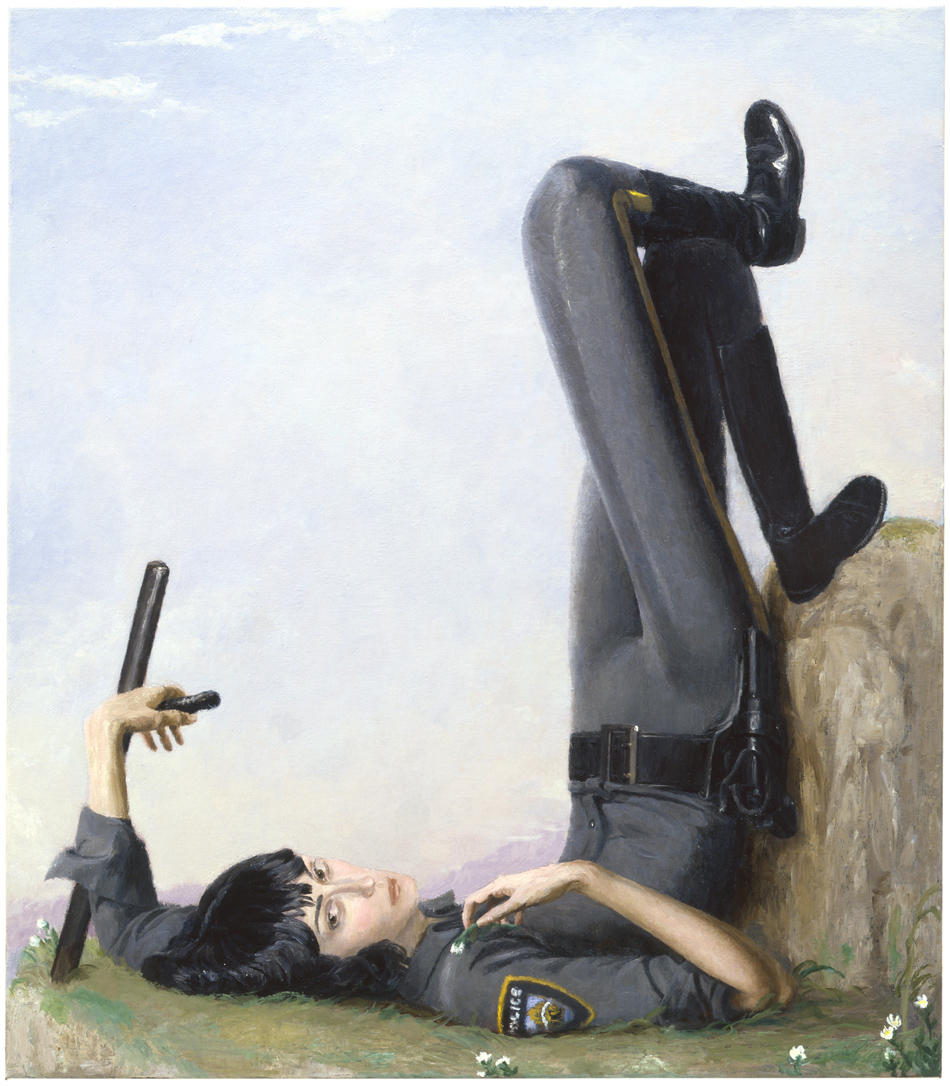

Great Plains © Jansson Stegner, 2007

Image courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery, London

You’re involved in another group show at Saatchi, ‘Body Language’. Which works of yours are in the show? Is the depiction and political potential of the body an important theme in your work?

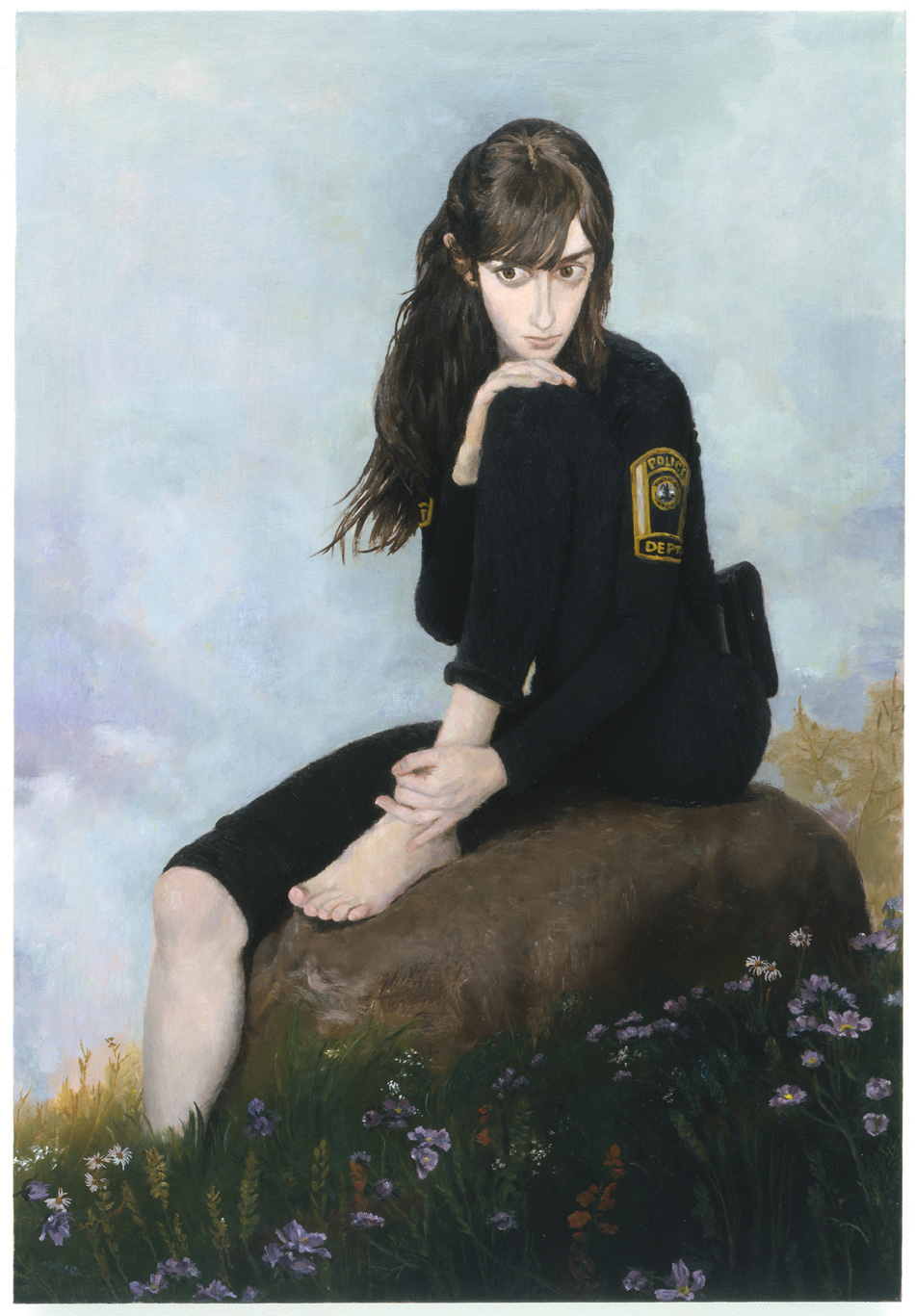

Starling Heights (2004), Grey Sky (2005), Great Plains (2006), and Sarabande (2006) are on show. I am interested in gender and power and beauty and strength. In my work, I like to take different signifiers of these things and put them together in unusual combinations. I want to come up with new ways to think about power. I think of these cop paintings as an allegorical ideal for new kind of state power.

Would you describe yourself as a narrative painter?

I have been a narrative painter in the past. My work from the early 2000s could easily have been described as narrative, although the narratives may have been very oblique. Today, I think of myself more as a creator of portraits of imaginary people. I think about the kind of person I want to paint then I cobble together bits from different sources to create it.

Your biography on the Saatchi website talks about the elements of ‘pop culture dumbness’ in your work as a tool. Do you think of camp and pop as subversive devices?

I don’t know if they are subversive anymore. Warhol’s soup cans are fifty years old. I think of them more as flavours to be added to a dish. Many of my painting strategies come from painters of the distant past. I love the Old Masters, but simply borrowing the Old Master aesthetic today feels tiresome and stuffy. Adding pop and camp elements are ways of spicing up the mix a bit. Blending opposites is a strategy I use both in the content and the aesthetics of my work.

Like Rego, many of your painterly themes are engaged in ambivalent reversals of power structures and, in particular, reversals and undoings of gender. What draws you to these themes?

I am interested in the new potential that arises from combining opposites. For example, painting a man in a beautiful and delicate (traditionally feminine) manner and painting a woman in a strong and powerful (traditionally masculine) manner creates new ways of looking at both.

And finally, apart from the group show at Saatchi, what’s next for you?

I will have a painting with Sorry We’re Closed at NADA in Miami in December and will be participating in a group show called “Hot, Dry Men, Cold, Wet Women” at Mark Miller Gallery in NYC in April.

Jansson Stegner‘s work will be on show in the exhibition Body Language at the Saatchi Gallery, London, from now until 14th March 2014.

Words / Edward Ball

Click the below links to view the newest Schön! Magazine Download Schön! the eBook

Schön! on the Apple Newsstand

Schön! on Google Play

Schön! on other Tablet & Mobile device

Read Schön! online

Subscribe to Schön! for a year

Collect Schön! limited editions